Reviews

Mike Hodges

USA, 1980

Credits

Review by David Carter

Posted on 06 June 2013

Source Universal DVD

Categories Failed Franchises

Flash Gordon was introduced to the American public in Alex Raymond’s 1934 thirteen-panel, four-color newspaper comic of the same name. A prime example of the comic format’s ability to tell compelling narratives, the comic became a near-instant success, captivating audiences with its “earth in peril” storyline and exotic, otherworldly settings. Flash Gordon would become the dominant force in American science fiction by the decade’s end, having been syndicated world-wide and adapted into three hugely successful serials starring Buster Crabbe in the title role. The serials would not be the last adaptation of the character, as Flash Gordon would be the focus of television and radio programs, cartoons, and comic books while simultaneously running in newspapers uninterrupted until 2003.

The failure of 1980’s Flash Gordon feature film is therefore considered something of an anomaly within the property’s otherwise continual popularity. Though international audiences reacted to the film more warmly, the film barely recouped its production costs in the larger North American market. Flash Gordon, American icon and the nation’s first space hero, had failed to win over his countrymen for the first time in his forty-six year history.

“Why?” was the question of the day regarding Flash Gordon, even though it was a question few observers were bothering to ask.

Critics were divided in their assessments of the film. Many dismissed it as overly campy, but some - Pauline Kael and Roger Ebert, to name but two - got the “joke,” as it were, and appreciated the film, its nod to the serials, and garishly over-the-top sets, costumes, and performances. No one championed the film outright, however, and the idea that the film was a failure has persisted in the years since, despite the fact it was in the top twenty-five highest grossing films of the year. Not a bad showing, to be sure, but an achievement that seems diminished when seen in context: Flash Gordon was released the same year as Friday the 13th, Raging Bull, Airplane!, and The Empire Strikes Back.

The success of George Lucas’ sci-fi serial is ironic, given that Lucas figures prominently in Flash’s somewhat convoluted journey to the cinema. Fresh off the success of American Graffiti, Lucas had attempted to purchase the rights to make a Flash Gordon feature film but couldn’t meet the asking price of the owner, Italian super-producer Dino De Laurentiis. Lucas proceeded to helm science-fiction of his own design. De Laurentiis himself had been unsuccessful in convincing his friend and fellow Flash Gordon fan Federico Fellini to direct the film, and the job finally fell to Get Carter helmer Mike Hodges. Flash Gordon was made and, in turn, released in the shadow of Lucas’ mammoth hits. De Laurentiis’ subordinate performance, measured against that of the Star Wars franchise, plays a large role in Flash Gordon’s undue reputation as a flop.

Simply put, Flash Gordon isn’t Star Wars. The film’s fans - myself included - are glad that it isn’t, however, as it offers viewers a unique cinematic experience. Enough has been written about how Star Wars changed cinema, but suffice it say Flash Gordon is from a world in which none of those changes had yet taken place. It is a film out of time; a work made in a vacuum. From both technical and thematic standpoints, Flash Gordon is essentially the same film that could have been made in the Fifties, Sixties, or Seventies. It eschewed the growing emphasis on special effects in favor of traditional “movie magic”—the handiwork of costumers, set designers, and other film artisans. Although it isn’t in need of redemption or reassessment, Flash Gordon embodies aspects of the craft of filmmaking, of which many modern viewers should be reminded.

The film is exceptionally faithful to its comic strip origins, albeit with minor changes to update the setting to a more modern era. The earth is pummeled by a series of mysterious natural disasters, confounding scientists and sending the world into panic. Only one man, Dr. Hans Zarkov, knows that these perils are extraterrestrial in origin, and he’s built a rocket to launch himself heavenward to find the source. Mere chance brings him two traveling companions - New York Jets quarterback Flash Gordon and travel agent Dale Arden - when a small plane is struck by meteors and crashes through his laboratory.

Zarkov’s ship passes through a black hole and enters into the orbit of Mongo, where it is brought to the surface by a tractor beam. The three earthlings are taken to the imperial palace where they learn that the various races of Mongo and its moons are ruled by the intergalactic despot Ming the Merciless, who is also responsible for Earth’s current situation. Flash demands that Ming stop his assault and unsuccessfully attempts to foment rebellion in the palace court, earning a death sentence from Ming for his troubles. Dale and Zarkov become a royal concubine and a brainwashed agent of Ming, respectively, but all hope is not lost for the trio. Ming’s daughter, Aura, saves Flash and spirits him away to Arboria, ruled by her lover Prince Barin. Barin despises Ming’s rule but is reluctant to help Flash in his fight to save the Earth, bristling at the idea of joining forces with his rival, Price Vultan of the Hawkmen. Increased pressure from Ming’s armies as they hunt for Flash changes several minds however, and Flash, Barin, and Vultan lead the combined peoples of Mongo in an all-out assault on Mingo City in a race to save the Earth.

Flash Gordon is unabashedly campy by design. But the camp is intentional, and this has been missed by many of the film’s detractors who wrongly thought De Laurentiis, Hodges, and company were attempting to make a serious sci-fi film as was the style in the early Eighties. Flash Gordon is a comedy. The confusion over its intentions is likely due to Lorenzo Semple Jr.’s scripting; he - the master of this brand of “is it, or isn’t it” deceptive camp - is best known for the Batman television series. Like Flash Gordon, many were unaware that Batman was actually a comedy, believing things like Bat-Shark Repellant to be earnest, but stupid, plot devices. Rather than adding comedy to the narrative, Semple merely presents an authentic version of the Flash mythos and calls attention to the inherent humor therein.

Flash Gordon mingles psychedelia with Pop Art, on which Raymond’s comic can be seen as an influence. The effect of this combination draws attention to the artifice of this film and indeed film itself. Viewers will be conscious of the fact that they are watching actors perform in front of cardboard and papier mach&eacut; sets at all times during the film, and it actively works to prevent suspension of disbelief. Rather than aiming for immersion, Hodges has designed the film to appear as if the performers have walked into a life-size version of Raymond’s comic strip. Bold, primary color costumes are set against ornate, but consciously false backdrops to create an aesthetic that is more Lichtenstein than Lucas.

Unlike some failed franchises, rumors of a Flash Gordon sequel are just that: rumors. Director Hodges and actor Brian Blessed have both stated that sequels were discussed, but no concrete details exist, likely due to the general disinterest in Flash Gordon upon its release. A sequel would have only served to diminish the film’s legacy, however, which continues to grow as home video releases have introduced the film to a more receptive group of viewers than it found originally. In my estimation, the appreciation is long overdue. So many elements of the film are imitable - Max Von Sydow’s performance, Queen’s soundtrack, Danilo Donati’s costumes — that any flaws one finds seem irrelevant.

More Failed Franchises

-

Captain Kronos - Vampire Hunter

1974 -

Doc Savage: Man of Bronze

1975 -

Zorro

1975 -

Flash Gordon

1980 -

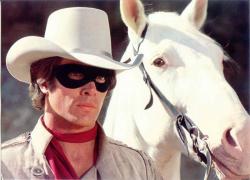

The Legend of the Lone Ranger

1981 -

The Adventures of Buckaroo Banzai Across the 8th Dimension!

1984 -

Supergirl

1984 -

Dune

1984 -

Masters of the Universe

1987 -

Howard the Duck

1986 -

Willow

1988 -

Dick Tracy

1990 -

The Rocketeer

1991 -

V.I. Warshawski

1991 -

The Shadow

1994 -

Godzilla

1998 -

The Zero Effect

1998 -

The Mod Squad

1999 -

Hulk

2003 -

Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World

2003 -

John Carter

2012

We don’t do comments anymore, but you may contact us here or find us on Twitter or Facebook.