Reviews

Werner Herzog

West Germany, 1977

Credits

Review by Rumsey Taylor

Posted on 09 August 2013

Source New Yorker DVD

Categories Favorites: The Apocalypse

Cutthroat portrayals of some fatalistic premise, Werner Herzog’s films often resemble the very tribulations they depict. This observation is emblematized in an anecdote from Herzog’s 1972 film Aguirre, The Wrath of God, in which an army of Spanish settlers descend an alarmingly steep portion of a Peruvian mountain. Given the terrain, they are armed with items of much unwieldiness: enormous iron canons, thrones, and cattle, materials with which they intend to establish an aristocratic realm. As they bobble precipitously downward, the throng of soldiers endeavors to keep their party moving and upright, and when one of the thrones bearing what appears to be the troupe’s princess falters, a hand reaches out from outside the composition and corrects it—the hand, according to legend, belongs to Herzog himself.

His productions wind so precariously toward the drain that, to Herzog’s enthusiasts, they evoke cinema at its most daring. But in a more impartial sense his films are absent of a certain discretion, and this is especially the case in his nonfiction films. In two of his documentaries - Little Dieter Needs to Fly and Wings of Hope - he collects the survivors of two different near-death experiences and compels them to confront the very circumstances that almost ended their lives. Both of these films are uniquely entertaining, but they raise questions as to Herzog’s tact in staging such an exploitative scenario, even if it is in the interest of catharsis.

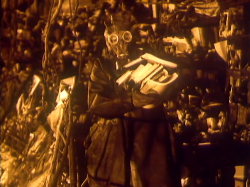

Yet such questions of ethics are largely dismissible, because Herzog so freely implicates himself in the risks his work engenders—a practice I think is clearest in his 1977 short documentary La Soufrière, named after an active volcano in Guadeloupe. Its eruption was gravely predicted by local scientists, prompting the total evacuation of Basse-Terre, a town that lies directly at the volcano’s base. Upon hearing of this, Herzog enlisted two cameramen and immediately set forth towards the deserted city.

Upon his arrival he describes the forthcoming eruption, his hypnotic monotone complementing the image of the mountain, which is at this point emitting a toxic, sulfurous gas. Basse-Terre is entirely vacant, and as Herzog and co. traverse its main streets, one may anticipate the decrepit, dated aura of a ghost town. Rather, it seems a normal Caribbean city: The stoplights are still functioning, all the adobe shingles that top the residences are properly in order, there are stray animals rummaging for food, and the front doors, even, of some of the residents’ houses are unlocked. These images, prior to Herzog’s quietly ominous ascent of the active volcano, are sharply peculiar, because they confirm the result of a tangible, momentous response to a natural disaster. The populous has suddenly, and without apparent hesitance, dispensed with all material comforts. Herzog roams about and remarks on the peoples’ vacation, equating their absence to a makeshift and troubled museum.

The film is permeated with great suspense, as though Herzog and his cameramen demonstrate an apparent obliviousness to a threat so pronounced that it encouraged the evacuation of hundreds of people. You’re nearly certain, when he arrives early in the film, that his indiscreet boldness will result in considerable misfortune, were it not for the fact that this realization precedes another: that you’re watching a completed film, which certainly wouldn’t have been the case had La Soufrière smothered Herzog and his crew in its fiery embrace.

In La Soufrière, as with the subjects of Dieter and Wings of Hope after it, Herzog confronts his own death pointedly, and this boldness is emphasized because he goes to a place that’s totally vacated, portraying him as the sole survivor of an enormous natural cataclysm. In his foray around the island, Herzog comes upon two others, both hermits who have opted not to vacate as they’ve nowhere to go. The volcano rumbling behind them, still emitting that sulfurous gas, their demeanor is one of quiet resignation: they perceive death to be inevitable, and this understanding absolves a fear that drives so many others away. It is clear Herzog thinks similarly, and has been very close to this thought in most every one of his films.

More Favorites: The Apocalypse

-

The War Game

1965 -

On The Beach

1959 -

Where Have All the People Gone

1974 -

A Boy and His Dog

1975 -

Bug

1975 -

La Soufrière

1977 -

Escape from New York

1981 -

The Road Warrior

1981 -

Le Dernier Combat

1983 -

Night of the Comet

1984 -

Threads

1984 -

The Terminator

1984 -

Def-Con 4

1984 -

Letters From a Dead Man

1986 -

Miracle Mile

1988 -

Last Night

1988 -

Last Days

2005 -

The Rapture

1991 -

Southland Tales

2006 -

Idiocracy

2006 -

The Happening

2008 -

The Road

2009 -

Cosmopolis

2012

We don’t do comments anymore, but you may contact us here or find us on Twitter or Facebook.