Reviews

Duccio Tessari

Italy / France, 1975

Credits

Review by David Carter

Posted on 05 June 2013

Source Turkish import DVD

Categories Failed Franchises

Johnston McCaulley’s pulp-hero Zorro has the distinction of establishing the tropes that went on to be the bedrock of the superhero genre: the mask and the secret identity. Zorro has also had the most adaptations into other media of any pulp creation, appearing in dozens of television and radio shows and scores of films beginning with 1920’s The Mark of Zorro. The popular Douglas Fairbanks swashbuckler appeared on the scene only a year after McCaulley’s 1919 introduction of the character, making Zorro the first truly multi-media property of the twentieth century. The filmic and literary Zorros were produced independently but continually referred to and influenced one another, thus granting the character a certain fluidity that other, more rigidly canonized characters lack.

This fact that each version of Zorro is different than those that have come before has caused a good deal of disparity in the successes of the roughly forty films in which the character has appeared. Fairbanks’ Mark was a smashing success that led to McCaulley reviving the Zorro character, who had retired at the end of his first novel. The 1998 and 2005 Antonio Banderas’ films The Mask of Zorro and The Legend of Zorro were equally successful, yet offered audiences a version of the character far removed from that of Fairbanks. In the near-century separating these two, a multitude of Zorros populated cinema screens, some of which were commercial successes. The most intriguing versions of the character appeared in Italian, French, and Spanish productions which saw Zorro paired with and against such historical characters as Samson, Queen Victoria of England, and the Three Musketeers.

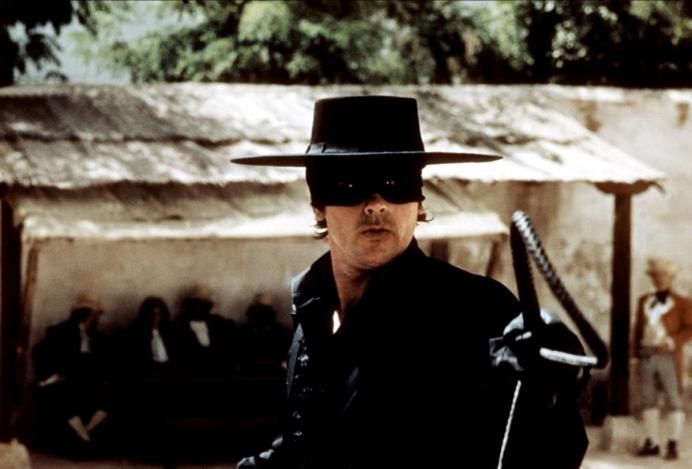

The 1975 French-Spanish co-production starring Alain Delon, Zorro, posits a much more traditional version of the character. Although Delon’s Zorro will be recognizable to viewers familiar with the Fairbanks version or the incarnation that appeared on Disney’s television show, the film emphasizes aspects of the character that were given little attention in many of the character’s filmic appearances. McCaulley’s depicted Zorro as a hero of the oppressed, and while this describes many interpretations of the character, this concept takes a much greater scope in Zorro. Though commercially and critically successful, this particular incarnation of the hero failed to catch on with other filmmakers, and thus remains the only time this particular version of the character appeared on screen.

Adventurer Diego has a chance meeting with his friend Miguel in a South American port city. The two men are traveling in different directions; Diego is returning to Spain, while Miguel is traveling to the interior to become the governor of Nuevo Aragon. Though friends, the two men’s philosophies are as different as their destinations: Diego is a world-renowned swordsman who tries to solve any problem with his blade, but Miguel is a pacifist, working for peace and equality for all. Miguel’s political rival, Colonel Huerta, has him assassinated before he can begin his journey to Nuevo Aragon. Diego makes a vow of revenge to his friend and promises to govern Nuevo Aragon in his place but Miguel insists with his dying breath that Diego do so peacefully, making him swear not to take lives in the pursuit of justice.

Diego arrives in Nuevo Aragon just as Colonel Huerta is trying to solidify power. Posing as Miguel, Diego pretends to be a cowardly fop as to not rouse suspicions about his true motives. Diego immediately notices the huge disparity between himself and the common people of Nuevo Aragon, who are politically and economically oppressed by Huerta’s soldiers and a justice system ruled by the aristocracy. Only the monk, Brother Francisco, stands up for the rights of the indigenous peoples of the area, drawing the ire of the colony’s rich and powerful. Diego resolves to help Francisco in his fight, but cannot do so as the governor. He decides to adopt the mantle of Zorro, a mythical hero of the indigenous people and the embodiment of the spirit of the black fox.

Zorro’s first public act is the rescue of Brother Francisco from the clutches of the corrupt judicial system. Rather than simply freeing Francisco, Zorro turns the judge and Francisco’s false accusers over to the people to suffer the same fate to which they had sentenced the monk. Next, Zorro appears in the marketplace to force Huerta’s soldiers to give the peasants a fair price for their crops. Diego ultimately realizes that true freedom and equality will be impossible with Colonel Huerta in control, and begins the execution of an ingenious plot wherein Zorro kidnaps Diego to force a showdown with Huerta and expose his corruption once and for all.

Zorro’s populism has been present in some form in all versions of the character, but Delon’s Zorro transforms this quest from one of justice to that of social justice. This is seen especially well in his conflict in the marketplace. Through his words during this scene, Zorro makes it clear that he is doing this not only because dishonesty is a moral wrong, but because the soldiers’ actions are economically oppressing the peasants. It is a shift in perspective from traditional Zorro films. Before, the soldiers’ crime would have been simply theft; here, it is shown to be oppression. These ideas recur throughout the film, with Zorro consistently on the side of egalitarianism rather than simple justice in a criminal or moral sense.

This shift in focus comes courtesy of the primary deviation Zorro makes from the standard Zorro tale. Zorro is most often set in California or northern Mexico, but here the story is moved to Latin America. Although colonialism occurred in both of Zorro’s traditional settings, those locales were not as tied to the idea of harmful colonialism as Latin America was and is, and certainly would have been in the minds of mid-seventies French audiences. In Zorro, not only are the peasants economically and politically separated from the upper class, they are a different race as well. Ideas of classism and racism appear throughout the film, and one gets the sense that this is the first truly socialist version of the character. This appears to have been done by design rather than accident, with the dialogue given to Zorro intentionally filled with incendiary appeals for revolution. This is seen best in the film’s climax, where instead of continuing to rule as a benevolent governor, Diego/Zorro turns Nuevo Aragon over into the hands of the people to rule as they see fit. The idea that the poor could lead themselves as capably as the aristocracy is notably absent from other Zorro films, which are concerned with reforming the aristocracy but continuing its position as the ruling class.

Zorro transformed the character from a proto-superhero into a revolutionary figure. The film only “failed” in the sense that this reading of the character was not reiterated in more films. Curiously, the American release of the film excised many expository scenes, thus removing the context of Zorro’s actions, effectively devolving the character into the quipping action hero with which American audiences were most familiar. The makers of the recent Blu Ray release of the film apparently still believe that American audiences aren’t ready for a revolutionary Zorro, as these scenes — which include Miguel’s impassioned pleas for justice — are still absent from the print. International audiences were more favorable to this version, however: a reported seventy million people saw the full version of the film in China, where it was one of the first western films allowed during the waning years of the Cultural Revolution.

More Failed Franchises

-

Captain Kronos - Vampire Hunter

1974 -

Doc Savage: Man of Bronze

1975 -

Zorro

1975 -

Flash Gordon

1980 -

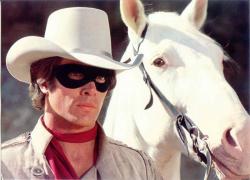

The Legend of the Lone Ranger

1981 -

The Adventures of Buckaroo Banzai Across the 8th Dimension!

1984 -

Supergirl

1984 -

Dune

1984 -

Masters of the Universe

1987 -

Howard the Duck

1986 -

Willow

1988 -

Dick Tracy

1990 -

The Rocketeer

1991 -

V.I. Warshawski

1991 -

The Shadow

1994 -

Godzilla

1998 -

The Zero Effect

1998 -

The Mod Squad

1999 -

Hulk

2003 -

Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World

2003 -

John Carter

2012

We don’t do comments anymore, but you may contact us here or find us on Twitter or Facebook.