March Fourth Two-Thousand Eleven

by Leo Goldsmith

Gilles Deleuze. Cinema 2: The Time-Image. 125.The screen itself is the cerebral membrane where immediate and direct confrontations take place between the past and the future, the inside and the outside, at a distance impossible to determine, independent of any fixed point… The image no longer has space and movement as its primary characteristics but topology and time.

2011 was the year in which, thanks to the soft duress of graduate school, I finally, laboriously, rewardingly worked my way through Deleuze’s Cinema books from beginning to end. As everyone knows, the French love movies almost as much as they love being obtuse, but Deleuze’s view of cinema, once one digs through cryptic Bergsonian musings about time and space, is also actually a fairly straight-ahead account of film history, paying particular attention to the evolution of styles and forms in a (perhaps unexpectedly) linear fashion. It’s the experience of cinema itself that is, for Deleuze, explosive, multivalent, and transhistorical, each frame a Kandinsky, each moment a crystalline concatenation of times and spaces, material events and flashes of consciousness.

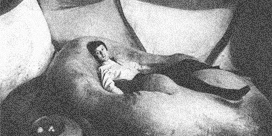

Not surprising, then, that among Deleuze’s many privileged filmmakers, Alain Resnais occupies a special place. Je t’aime, je t’aime, perhaps most of all, typifies Deleuze’s multi-planar conception of time, and so it was fortuitous to catch a rare 35mm screening of Resnais’s film as part of the Museum of the Moving Image’s retrospective in March. A time travel film like no other, Resnais’s film depicts the journey of his lovelorn, suicidal chrononaut as a series of passively relived experiences rather than a few touristic jaunts through different times. Resnais’s protagonist is haunted by a past that is deeply, inexorably embedded in his present, and his experience of time, nominally enjoyed from the cushy interior of a giant, brown-velvet-upholstered egg, notably resembles Deleuze’s description of the spectator’s encounter with cinema.