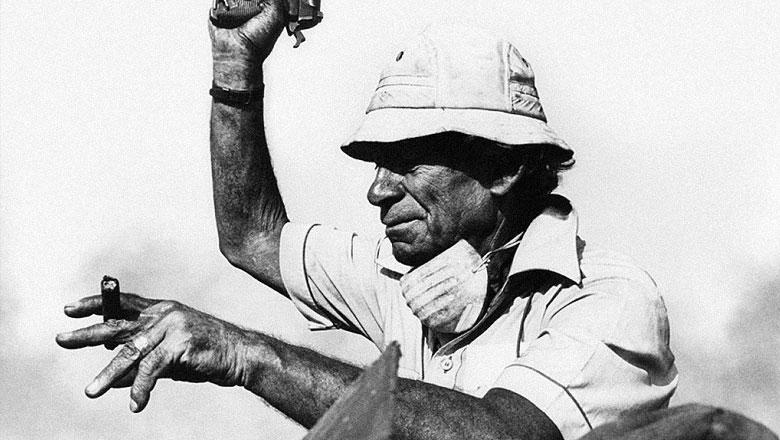

Samuel Fuller would have been 100 this year. Throughout his long and exciting life, Fuller was a modern day factotum. Reporter. Novelist. Soldier. Devoted father and husband. Actor. Runway model. Filmmaker. And while his first and last movie industry credits were as a screenwriter (1936’s Hats Off and 1994’s Girls in Prison, respectively), Fuller is best remembered for his work as a director. Films like Pickup on South Street (1953), Shock Corridor (1963), The Naked Kiss (1964), and The Big Red One (1980) are bona fide classics. Over the years, Fuller’s reputation has changed from industry outsider to something of an icon amongst filmmakers and moviegoers alike.

Fuller’s directorial body of work comprises 22 theatrical feature films, 3 made-for-tv features (Dead Pigeon on Beethoven Street, Day of Reckoning, and The Madonna and The Dragon), and numerous television episodes (chiefly Iron Horse, as well as other shows). His first film as director, 1949’s I Shot Jesse James, was a small, independent production whose modest means belied its brazen, daring vision of a ruthless, psychotic West. Fuller challenged the cultural mythology of the West, daring to look beneath the archetype of the Jesse James-Bob Ford legend to uncover the raw emotions and motivations at the heart of their actions. The result was a radical re-visioning of the West filled with characters, ideas, and feelings relatable to modern day audiences. Only one film into his career, and Fuller had defined the facets that would be present throughout his career: politically-charged stories blending philosophy, poetry, and violence. Fuller’s major innovation, and personal invention, was to turn cinema into an editorial. Even his final feature, the 1994 made-for-television movie The Madonna and the Dragon, which is set during the People’s Revolution in the Philippines, exhibits the same reporter’s eye for drama and poetic-politic fusion that defined his career.

While his bold personality and defiant, unconventional style put him at odds with the classical Hollywood studio system, it has made him a hero to generations of cineastes. Fuller began as an independent writer/director, and even though he did move over to Fox to work with legendary producer Darryl Zanuck, he wasn’t afraid to leave when his vision didn’t align with the studio. When Zanuck wanted to turn Park Row into a Technicolor musical, Fuller decided to finance the film himself, turning himself into a truly and totally independent filmmaker. For the rest of his career, Fuller did work both independently (Shock Corridor, The Naked Kiss) and with studios (White Dog for Paramount), but one thing remained constant: Fuller was an artist with a vision, and he refused to compromise. Fuller knew the dangers of being independent—lower budgets, smaller releases, potentially treacherous producers or financiers. Occasionally, cuts were beyond his control, such as with Caine, a film about Mexican gun runners that was cut up by the producers without Fuller’s knowledge, and turned into an incomprehensible mess known as Shark. But even studio-produced work could be uncertain. Paramount shelved the controversial White Dog because of threats from the NAACP—their criticisms of racism, it should be noted, were unfounded. Fuller’s steadfast commitment to his own ideals, however, paid off. Fuller’s body of work is fully his own, a deeply personal series of films that, despite occasional peaks and valleys, is extraordinarily consistent in terms of craft, personality, and vision.

Such varied filmmakers as Claude Chabrol, Dennis Hopper, Luc Moullet, and Wim Wenders all paid their respect to Fuller by giving him small cameos in their films. The biggest and most insightful tribute was Jean-Luc Godard’s Pierrot Le Fou. For a party scene, Godard asked Fuller to play himself. The scene is lasts only a few seconds – a couple brief lines between Fuller and Jean-Paul Belmondo, who asks, “What is cinema?” – but the exchange has become something of legend. Fuller recounts in his memoir, A Third Face:

Without the faintest idea of what I was supposed to say, I showed up at a studio on the outskirts of Paris the day of the shoot. […] We never rehearsed the damn scene. I wasn’t sure what Jean-Luc wanted, so I took a puff on my cigar and played myself, blurting out a line in my tough-guy vernacular, which a bilingual lady repeated in French as I spoke: “Film is like a battleground. There’s love, hate, action, violence, death… in one word: emotion.”

It’s the perfect summation of Fuller’s own aesthetic, and arguably the most romantic, yet accurate, definition of “cinema” ever given.

Fuller’s reputation continues to grow every year, garnering new critical praise and gaining new generations of fans. And now that his films are more widely available and easily accessible than ever before, fans can look beyond his canonized works and discover the breadth and depth of his filmography. Samuel Fuller: Deep Cuts examines the lesser-known battlegrounds of his career. Over the next week, we will highlight films of his that, while lesser-known, are crucial milestones in his filmography, personal favorites here at NotComing.com, and just damn fine movies. In conjunction with this feature, we will be screening a personal favorite of Fuller’s, Park Row, in 35mm at 92YTribeca on Saturday, November 24th. If you are in the New York City area, drop on by and pay tribute to this cinematic legend.

Introduction by Cullen Gallagher

By Cullen Gallagher, Leo Goldsmith, and Thomas Scalzo ©2012 NotComing.com

Reviews

-

Verboten!

1959 -

Park Row

1952 -

Underworld U.S.A.

1961 -

The Day of Reckoning

1990 -

The Madonna and the Dragon

1990

We don’t do comments anymore, but you may contact us here or find us on Twitter or Facebook.