Reviews

An Alan Smithee Film: Burn Hollywood Burn

Alan Smithee (Arthur Hiller)

USA, 1997

Credits

Review by David Carter

Posted on 04 June 2014

Source Walt Disney Video DVD

The Director’s Guild of America had a policy for many years by which a director could “disown” a film if he felt that his creative control had been usurped; he would be allowed to be credited as the pseudonym “Alan Smithee.” This was an open secret in Hollywood: even if the director’s involvement in a film was public knowledge, the pseudonym was more an act of protest rather than an attempt to save face. The DGA no longer allows directors to use an Alan Smithee credit, one of the many unforeseen consequences of the 1997 film An Alan Smithee Film: Burn Hollywood Burn.

Burn Hollywood Burn presents itself as a documentary on the scandal surrounding Trio, a “$220 million dollar” action film starring Sylvester Stallone, Whoopi Goldberg, and Jackie Chan, who appear as themselves. Renowned action film editor Alan Smithee was hired to direct because producer James Edmunds and studio exec Jerry Glover felt he would be easily controlled. After learning that Edmunds has final cut of the film, Smithee wants his named removed but is unable to use the standard pseudonym because it is coincidentally his real name. Smithee then steals the master copy of the film and threatens to destroy it, inadvertently making Trio the hottest film in Hollywood sight-unseen and becoming a folk hero in the process.

Much has been made about the film’s lackluster direction and the phoned-in performances, but Burn Hollywood Burn’s problems begin at a conceptual level. It utilizes a mockumentary format, and one imagines that the film was pitched as a parody of Hollywood in the vein of This is Spinal Tap’s endearing conception of the music industry. That at least appears to be what Eszterhas was aiming for, but the primary difference between the two films is the audience’s familiarity with the institutions being satirized. Spinal Tap lampooned the excesses of rock music and rock musicians well-known to audiences of any background; Burn Hollywood Burn makes its satirical attacks primarily against Hollywood producers, studio executives, and agents—groups that are largely oblique to even diehard cinephiles. Eszterhas’ mistake was failing to realize that, no matter how well-crafted, his satirical barbs and in-jokes would be lost everyone in America except the very people he was mocking.

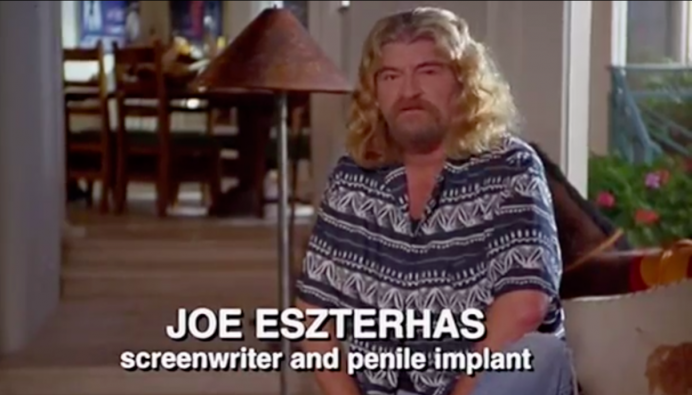

Although Spinal Tap was satirizing real world personages and events, very few would consider the film’s humor malicious. Eszterhas’ Burn Hollywood Burn has an axe to grind, however. In the span of three years the screenwriter had seen both great success in Basic Instinct and much ridicule in Showgirls, and Eszterhas’ bitterness about Hollywood’s capriciousness is very much on display here—there is ample evidence to support a reading of the film as autobiographical. Eszterhas reportedly considered having his name removed from 1995’s Jade because, much like Smithee, he felt the film had been taken away from him. There are repeated references to the criticisms Eszterhas received for Basic Instinct and Showgirls and, in the film’s most infamous line, Smithee declares Trio to be “worse than Showgirls.” Lastly, on-screen text introduces each of the speakers in the film, and almost all are listed as a being a feminist except for Eszterhas, of course, in his cameo, furthering the idea that Burn is a response to his perceived persecutions.

Nowhere is this the film’s antagonism more evident than in the de facto main character of “super producer” James Edmunds, very transparently based on Robert Evans, who Eszterhas had worked with on Sliver and Jade. In an interesting twist, Evans is also in Burn Hollywood Burn as himself. The fictional Edmunds lives out all of the unscrupulous things the real Evans has been accused of doing, from drugs to prostitution to murder. Burn Hollywood Burn dedicates a good deal of its running time to directly mocking Evans. Perhaps he was unaware of film’s content other than his own scenes, but it is entirely possibly that Eszterhas used Evans’ notorious ego against him, having him appear in the movie to compound the insults. Additionally, Evans’ involvement with the film is a prime example of why Burn Hollywood Burn was unable to connect with audiences. Evans released his autobiography The Kid Stays in the Picture in 1994, but the popular documentary of the same name had not yet been made, meaning the minor notoriety among the general population he enjoys today did not exist in 1997. Therefore any reference to Evans’ persona or specific events from his life — of which there are many in Burn Hollywood Burn — would be completely lost on the average viewer.

A more problematic aspect of the film involves the “African-American Guerilla Film Family,” a group of underground filmmakers who give Smithee a place to hide. The AAGFF is the only group in the film besides Smithee that is shown to have a respect for cinema as an art form rather than simply a commercial product. Burn Hollywood Burn contrarily shows the African-American characters to be intelligent and virtuous, but at the same time only allows them to speak in stereotypically profanity-laden slang. It isn’t readily evident if Eszterhas is attempting to satirize Hollywood depictions of African-Americans or not, but if that was his goal, he was certainly unsuccessful. The AAGFF is led by the Brothers Brothers, who, as with Edmunds/Evans, are transparently based on Albert and Allen Hughes. It is not clear why Eszterhas would so obviously reference the Hughes Brothers — the film even makes veiled references to their Armenian heritage — and, more so, why he would depict them in such a negative light.

In his attempt to exact revenge on Hollywood, Eszterhas doesn’t appear to be concerned about burning bridges. But it wasn’t the film’s blatant attacks that severed Eszterhas’ Hollywood ties; rather, it was the fact that it was one of the most spectacular flops in history. The film effectively ended the careers of Eszterhas and Arthur Hiller, and it also marked the end of its film studio, Cinergi Pictures. It’s as though the film succeeds at antagonizing those whom it satarizes, and in result it is so noxious that few have opted to encounter it.

We don’t do comments anymore, but you may contact us here or find us on Twitter or Facebook.