Credits

Feature by: David Carter, Victoria Large, Thomas Scalzo, and Rumsey Taylor

Posted on: 31 October 2011

Related articles:

Features

31 Days of Horror VIII

John Wintergate claims that it started innocently. He and his girlfriend Kalassu wanted to make a comic spoof of horror films, but knowing that their limited abilities would require countless retakes, they chose to shoot BoardingHouse (1982) on the cheaper and easier to manage video format rather than film. Wintergate admits that he intended the film to be bizarre, but it is unlikely that he was aware at just how far BoardingHouse strayed from the bounds of traditional horror—or cinema itself. Stephen Thrower called the film “cinema from another dimension” in Nightmare USA and went on to say, “It’s probably a good thing after all that there are so few films like BoardingHouse: we might get used to them, and never enjoy a coherent movie again.” A wholly unique cinematic experience, BoardingHouse also has the distinction of being the first shot-on-video horror film and helped establish the pattern of incoherence and insanity that would come to typify the genre.

In 1983, Sony and JVC released the first consumer “camcorders” to the public at large. Previously, shooting on video was limited primarily to television production due to the size and expense of the equipment, and the new camcorders offered the dual benefit of being battery powered and operable by a single person. While this was certainly a large technological milestone, it was a particularly important development in the world of independent filmmaking. The release of affordable 8mm and 16mm cameras had swelled the ranks of independent features in decades prior, but the formats still had technological challenges (the expense of developing film footage, for one) and required the purchase of other equipment for editing or transferring. The Sony and JVC camcorders eliminated practically all of these hurdles and marked the first time that truly anyone with enough initiative could make their own movie.

Video was the perfect format for the horror genre, which was the traditional home of low budgets and neophyte filmmakers. The genre was slow to take off in the wake of BoardingHouse, however. The next known SOV horror film was David A. Prior’s 1983 effort Sledgehammer. It is unknown whether Prior was aware of BoardingHouse, but Sledgehammer closely resembles a traditional slasher film filtered through the demented illogic of Wintergate’s film. It is important to note that while BoardingHouse received a theatrical release after being blown up to 35mm (director Wintergate states that it was programmed with Jaws 2 in some markets), Sledgehammer was released direct-to-video. The commercial success of either film is unknown, but perhaps some insight can be gleaned from the fact that Prior went on to direct such horror/exploitation classics as Killer Workout and Deadly Prey and Wintergate released no other films. The commercial success of the next SOV horror film would be substantial enough to usher in the genre’s boom period and move independent horror cinema’s headquarters far away from Hollywood or New York.

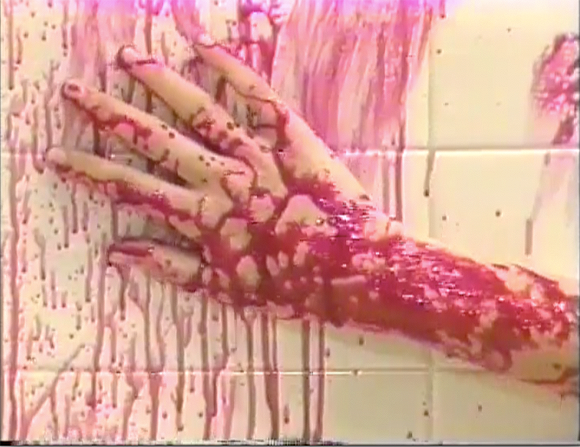

Christopher Lewis, son of Oscar winning actress Loretta Young, filmed Blood Cult (aka Slasher) in Tulsa, Oklahoma, in 1985. Blood Cult begins in much the same way as Hollywood’s slashers: a sorority house, a showering co-ed, and a lengthy POV shot culminating in a meat cleaver murder. The dog cults, bloody dismemberments, and stilted dialogue that followed showed how great the divide between Blood Cult and its more polished compatriots truly was, however. Lewis’ film tempered the insanity of BoardingHouse and Sledgehammer with more gore, and to much success. It was more coherent than its predecessors, but only by a small degree, and although later SOV horror films would match or better Blood Cult’s level of gore, a tendency for the bizarre would come to describe the sub-genre in whole. Lewis would go on to make another entry into the SOV horror canon, The Ripper, starring special effects wizard Tom Savini, but opted to shoot Revenge, a sequel to Blood Cult starring Patrick Wayne, on 16mm.

Both SOV horror and direct-to-video horror were emerging at the same time, and a multitude of one-release filmmakers and one-release video companies soon followed. Of those companies that would become established, Camp Video is the one most closely associated with SOV horror and survives into the present day, releasing many of the same films on DVD. Camp, like many other labels, supplemented its SOV horror titles with a plethora of low-budget horror, exploitation, and foreign titles, and it was also not uncommon for SOV horror filmmakers to handle their own distribution.

Shot-on-video horror’s life was a brief but memorable one. The genre faded away not because of any single factor but a combination of many, both artistic and economic. First and foremost, filmmakers’ tenures in the genre were typically brief; some moved to bigger, non-video projects, but for many one SOV horror film would be the only one they would produce. Secondly, technological advances rang the death knell for SOV rather quickly—the first digital camcorders were introduced just six years after the first video camcorders and by 1995, DV became the standard for independent filmmaking. Furthermore and perhaps most importantly, the slow decline of the independently owned video store sped up SOV horror’s demise. Chain stores were far less likely to give their valuable shelf space to films like Splatter Farm or Gore-Met, the Zombie Chef from Hell, effectively eliminating their market.

The weird, wild world of SOV horror is therefore a fitting way for us to end the eighth installment of 31 Days of Horror. Join us as we journey through the genre’s highs and lows and, much like the films themselves, it’s guaranteed to be an unforgettable experience.

Introduction by David Carter

Sledgehammer

- USA / 1983

- Directed by David A. Prior

- Intervision DVD

Sledgehammer occurs predominantly in a cabin in a wooded area, or so it’s described by the teenagers who enthusiastically seek leisure in it in the second part of the film. More aptly, it is a completely normal, templated apartment, the sort that constitutes a tower complex on the rim of an urban suburb. The kitchen has contemporary appliances, the walls are clean and empty, and the doorknobs, trim, and mirrors are all bereft of the mossy patina that describes all cabins in the woods everywhere.

This discrepancy between the actuality of the film’s setting and the characters’ and filmmakers’ conception of the same is in service to Sledgehammer’s constant illusion. It is decidedly oblivious, like most cheap, on-the-fly horror films, to its modest craft, aiming whole-heartedly for scares and suspense becoming of a film many orders of magnitude higher than its level of capability. Sledgehammer is at first a textbook slasher, opening with a flashback that will conclude in revelation at the end, but it culminates with ambiguity. This ambiguity differentiates it from other cheap teenagers-in-a-cabin horror films with which it is customarily associated.

I attribute its ambiguity to the constraint of its setting and cheap production. For one, the video footage is edited prosaically, its chief stylistic flourishes being slow-motion and cross-fading. The killer is a shape-shifter, and he’s established many times in a shot that blends into his form as a young boy, the same one from the film’s violent preface. And when he’s seen in closeup, the image is strewn forgivably in rows of fuzzy resolution that make it near impossible to identify him as someone we saw earlier in the film.

Sledgehammer was the first film from the Prior brothers, Ted (the actor) and David (director), who would produce heaps of cheap action movies in the 1980s and 90s. In the two Prior films that I’ve seen (another of their early horror films, Killer Workout, I enthusiastically recommend) the male characters are all hulked up. If this seems a peculiar observation, know that Ted, for one, spends half the film shirtless and often at seemingly inopportune moments—when he’s grappling with the slasher killer, the shirt is suddenly gone and his muscles become the film’s paramount feature in contrast to the killer’s comparatively normal build. It comes as no surprise whatsoever that he will emerge victorious, after a battle that leaves him with little more than a limp, but the victory is uncertain. The final shot pans up as Ted and the lone female survivor limp victoriously out of that cabin, and rests on the image of the slasher killer, looking at them from a second-story window, that they so greatly endeavored to disable.

Review by Rumsey Taylor

Blood Cult

- USA / 1985

- Directed by Christopher Lewis

- VCI VHS

In the winter of 1985 one of the strangest series of murders in recent history shocked a small mid-western college campus.

Blood Cult establishes its atmosphere of disquiet in the above preface, which is rendered wholly unnecessary once the murders have ensued. The film contains plenty of them to satisfy its reasonably lean 90 minutes, and most each of them are depicted with the same strategy: told in the killer’s POV, his black-gloved hands grabbing out from behind the composition, these sequences sketch the killer via his implements of harm, framing a poised meat cleaver, for example, or composing his hands in closeup as they strangulate one of the more resistant victims.

This strategy should be familiar, as it’s not unlike that of a giallo film or other cheap American slashers. As such, Blood Cult is formulaic to a fault, but it retains some modest prestige in – paradoxically, like other cheap horror films – how devoted it remains to its flimsy, familiar premise. This, and its shot-on-video aesthetic which does well to disguise its ineptness. At times this aesthetic lends the proceedings an air of camp: the local sherif, somewhat isolated in his determination to identify the serial killer, checks the time on a late-night stakeout, and he announces it out loud because the closeup that frames his wristwatch is so fuzzy we can’t read it. The murders, however, are uncharacteristically grisly, and the blood that strews the crime scenes glistens starkly as if it is fresher – as if it is realer – than what we are normally accustomed to in other horror films.

The film’s cinematography seems to feature a range of optical filters – the night scenes inherit a blue hue, for one – and the composition has a fish-eye halo about it, as if the whole story is from the perspective of an omnipresent character. This further enhances an aspect of realism that becomes Blood Cult’s paramount hallmark. And like other films that share its modest, unpretentious manufacture, viewing it on VHS is its optimal form of exhibition.

Review by Rumsey Taylor

Gore-Met, Zombie Chef from Hell

- USA / 1986

- Directed by Don Swan

- Camp Video VHS

Throughout my childhood and adolescence, Friday night meant a trip to the local VideoXpress, where I invariably would make a beeline for the horror section. It changed little week to week, but nevertheless I would methodically scan each box in hopes that some new form of terror would catch my eye. Frequently I would be drawn to the Camp Video release of Gore-Met, Zombie Chef from Hell. My knowledge of the film was strictly limited to what was on the VHS box, which was emblazoned with a severed arm that had neatly been sliced like deli meat by a large cleaver. Helped by the tagline “The devil incarnate must have human blood to perpetuate his evil existence,” Gore-Met practically leaped off the rack and grabbed you by the collar and demanded that you watch.

It was not to be, however. The same effective marketing campaign that drew me to the film raised a red flag for my parents: Gore-Met would have to remain forbidden fruit. Even then, I knew enough about how the film industry worked to know that I couldn’t expect to sneak out of bed and catch Gore-Met on Cinemax one late night either. Once I was old enough to make my own decisions about video rentals – and drive myself to the store – VideoXpress was long gone, driven out of business by the flashy new, Gore-Met-less Blockbuster Video down the street.

By my college days, Friday nights had changed only slightly and involved a map, a handwritten list of “must-sees,” and the “V” page of the local phonebook I had appropriated from a phone booth. Many trips on the back roads of neighboring cities and towns were successful, but perhaps none as much as when I finally laid my hands on Gore-Met, Zombie Chef from Hell. Despite having read the box hundreds of times and waiting almost a decade to see it, I was ill-prepared for what awaited me.

The basic plot is simple. Writer/director/producer/music supervisor/distributor Don Swan’s film borrows heavily from Blood Feast and others with its story of a cannibal who serves his victims to the unsuspecting customers of his restaurant. Swan takes this formula far beyond those earlier films, however. The titular Zombie Chef is Goza the Philosopher, a 13th Century cultist condemned to immortality for the crime of eating the high priest. The ironic – or inane – twist on his curse is that he must continue to eat human flesh to live. Goza’s former cult members apparently are immortal as well, and his nemesis Azog attempts to stop Goza using his telekinetic powers, and the ensuing invisible battle between the two immortals is perhaps the most bizarre fight sequence in the history of cinema. A weakened Azog passes the job of defeating Goza to a librarian/high priestess named Sara, who ultimately defeats the cannibal by super-gluing his lips shut.

If this written outline of the narrative sounds like a bizarre fever-dream, please understand that watching it unfold is one of the greatest cinematic challenges in the horror genre. Gore-Met rivals BoardingHouse in terms of SOV indecipherability. One wonders what Swan’s intentions for the film were. There are hints that it was meant as a comedy, but the film’s most laughable moments are played with deadly seriousness. Several sequences appear as if Swan merely left the camera running during an average night at the bar where it was filmed. The majority of the film’s seventy minute running time is irrelevant to the plot, but as the minutes tick by it becomes increasingly hard to look away.

My inclination to look for a film’s meaning makes this jumbled nonsense infinitely compelling and I’d wager that most viewers will have a similar reaction to the film. Even though my cinematic excursions frequently take me to the outer fringes of cinema, Gore-Met will always hold a high position on the list of the strangest things I’ve ever seen. The film has an odd quality that I wouldn’t have appreciated when I was younger; Gore-Met was definitely worth the wait.

Review by David Carter

The Last Slumber Party

- USA / 1988

- Directed by Stephen Tyler

- Amazon Instant Video

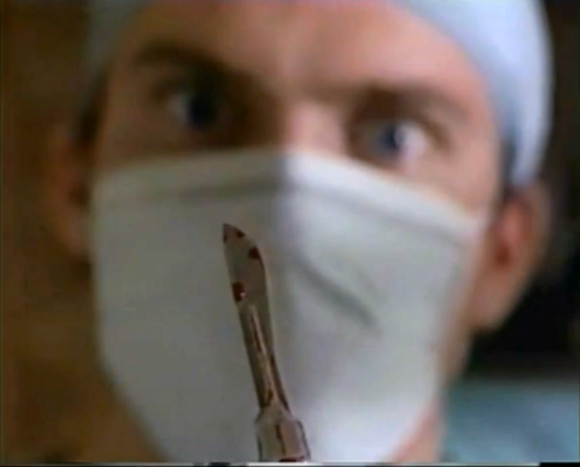

The Last Slumber Party is derivative slasher nonsense with low-rent effects and a fairly incomprehensible storyline, the kind of thing that enters people’s lives via late night video store runs and bargain DVD bins. It’s a movie that requires patience, and doesn’t do all that much to reward it. But somehow, when I was watching it, I couldn’t help noticing that Slumber Party’s writer-director Stephen Tyler (who also plays this slasher’s requisite bug-eyed maniac, and who is not Steven Tyler, the lead singer of Aersomith) seems to have a sense of humor about his project.

Take, for example, the opening scene in which a high school science teacher offers his students a rambling end-of-the-year goodbye speech in which he deadpans, “I know that I’ve certainly been an inspiration to all of you,” or the Sesame Street poster that cheekily appears in the background of countless shots. Even the characters feel oddly parodic: their obliviousness to the fact that a scalpel-wielding escaped mental patient in doctor’s scrubs is stalking around one particular house and offing people is so silly that it begins to feel like a running joke. The characters themselves are so nasty and dopey (speaking mostly in homophobic and misogynistic insults) that they seem like intentional caricatures of the kinds of horror movie characters that viewers just want to see dead. Tyler seems well versed in his genre, lifting rather heavily from Halloween, and somehow Slumber Party lacks the guileless sincerity of, say, an Ed Wood picture.

But at the same time, the movie is cheap and wobbly enough – at one point we can actually see an actor squeezing his own squib – that it becomes easy to doubt whether the humor is intentional at all. My favorite moment from The Last Slumber Party comes early on, and is for me emblematic of the entire project. A doctor and nurse share the following exchange about Tyler’s bug-eyed mental patient:

NURSE:

He said he’d kill you or anybody else that tried to cut out part of his brain.DR. SICKLER:

Which is just exactly why we have to do just that.

The way the actor playing Dr. Sickler stumbles over the line, and the silliness of the exchange itself, makes me smile, and I have no idea whether it was meant to be funny or not. I like to think that it was, though. That more or less sums up The Last Slumber Party, a shoddy but strangely amusing piece of work from a bygone era of low budget filmmaking.

Review by Victoria Large

Woodchipper Massacre

- USA / 1988

- Directed by Jon McBride

- Camp Motion Pictures DVD

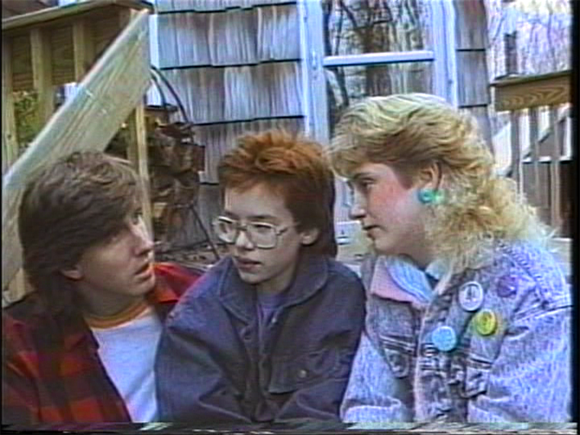

If you’ve never settled in for an evening of Shot-on-Video horror, it may be hard to understand how a film like Woodchipper Massacre could ever be recommended viewing. The distractingly digitized credit sequence, the tedious opening scene of a young man feeding branches into a woodchipper, the persistent hiss on the audio track, the obvious non-actors either stumbling through their lines or grievously overacting, the list goes on and on. In other words, anyone on the lookout for high-quality production values, a gripping storyline, and realistic gore, will be sorely disappointed if they choose Jon McBride’s shoestring Connecticut creation for their evening’s entertainment.

In order to properly appreciate – and enjoy – a labor-of-love effort like Woodchipper Massacre, however, you must first adjust your expectations of what constitutes quality horror-themed entertainment. Concerns about narrative logic must be immediately brushed aside. Technical gaffes should be expected and actively sought out. Acting incompetence and dialogue delivery snafus should be welcomed with open arms. And oddities of characterization must be celebrated. Only then can you begin to understand the appeal of SOV horror, and appreciate why Woodchipper Massacre deserves 80 minutes of your time.

The story, initially, is relatively straightforward: a single father’s business responsibilities require him to leave his three children – Jon, Denise, and Tom – in the care of their crotchety Aunt Tess. Through an unfortunate series of events – including young Tom somehow ordering a lethal hunting knife through the U.S. Mail – Aunt Tess is killed. And that’s when things take a turn for the unexpected, and launch Woodchipper Massacre into the realm of black comedy horror. Unsure of how to handle the situation, the kids, afraid of getting in trouble for inadvertently killing their aunt, chop her into bits and send her through the woodchipper.

Admittedly, this story shift took me by surprise. When considering the potential implications of the film’s title, never did it cross my mind that the titular machine would be operated by a trio of desperate kids attempting to dispose of a member of their family. Yet even in the midst of watching Aunt Tess being dismembered and subsequently sent through the chipper, the surprisingly morbid elements of the horror story did not endear me to the film as much as the ludicrous and charming non-horror elements surrounding them.

First up is the unparalleled fun of staring at young Tom, he of the inordinately large head and oversized glasses. Aside from wondering how he was able to order a huge, deadly knife through the mail, we can’t help but be curious as to exactly how old he’s supposed to be. He looks like he’s 8, but he often acts like he’s the only adult in the house. And there’s something so unpleasantly ungainly about him – maybe it’s his orange hair mullet, or his uncoordinated air guitar solos – that I was half inclined to shut my eyes every moment he was onscreen. But of course, I did not.

Next in line is the joy of listening to every word uttered by teenaged Denise. Not dissuaded in the least by her thick braces, feathered bangs, or goofy hoop earrings, Denise earnestly shouts her way through all of her conversations, whether standing next to her brother at the mailbox, or addressing her Aunt Tess as they clean up the kitchen together. The intensity of her delivery makes even the most mundane statement loaded with unintended importance, and makes you wonder if the actress was in need of some aural augmentation.

Once the deed of disposing of Aunt Tess is done, and the siblings attempt to find a way out of their mess, the film reaches a crescendo of inanity with Denise enthusiastically chatting on the phone with her boyfriend, and her brothers trying frantically to remind her that the dead body in the kitchen should be dealt with before inviting over any guests. Couple such ridiculousness with moments like the interminable long shot of a car backing out of the driveway, driving down a long, tree-lined street, putting on its blinker, turning right, and finally driving out of frame, and the camp appeal of Woodchipper Massacre should be evident.

And yes, it is camp. But it is camp in service of an actual horror storyline. Writer/Director/Producer Jon McBride may not have had the most competent actors at his disposal, or the most competent crew, but we never feel that his goal was to create a comedy with some horror elements. On the contrary, from start to finish, Woodchipper Massacre has the hallmarks of a film envisioned as a genuinely dark horror film, but one that had the good sense to segue into comedy when the narrative or production conditions demanded it. The end result is a charming horror adventure, full of ridiculous characters, overblown dialogue, and an engaging, low-budget spirit that’s hard to resist.

Review by Thomas Scalzo

By David Carter, Victoria Large, Thomas Scalzo, and Rumsey Taylor ©2011 NotComing.com

We don’t do comments anymore, but you may contact us here or find us on Twitter or Facebook.