Reviews

Shatranj ke Khilari

Satyajit Ray

India, 1977

Credits

Review by Ian Johnston

Posted on 26 June 2006

Source Kino Video DVD

The Chess Players is famously Satyajit Ray’s first film not in his native Bengali language; it’s in Urdu, the language of the Muslim rulers of northern India (and subsequently the official language of Pakistan), which, along with closely-related Hindi, appear to have been effectively foreign languages for Ray: he wrote the screenplay originally in English and had it translated, as he did with his only other non-Bengali film, the 52-minute TV film Sadgat/Deliverance that he made in Hindi in 1981.

The film is sometimes singled out as something different for Ray because of its historical setting, but in fact this was not the first Ray film to have such a setting. Charulata takes place in the late nineteenth-century (a specific setting Ray would return to in his last great masterpiece Home and the World), Devi/The Goddess in the 1860s, Distant Thunder during the Bengal Famine of 1943-44, and other Ray works, being based on literary texts often decades-old, frequently have the feeling of being set in an earlier time. The first two Apu films Pather Panchali and Aparajito, The Music Room and Three Daughters, are examples of this.

But it is true that The Chess Players contains more of a history lesson than the other films. The historical subject is the British annexation in 1856 of the Kingdom of Oudh and its capital Lucknow and the forced abdication of its decadent ruler, Wajid Ali Shah. The early part of the film gives us an explanatory voice-over illustrated with maps, documents, historical paintings, and even a rather bizarre tone-breaking piece of simplistic animation. This portrays the British Governor-General Lord Dalhousie gobbling up cherries, each one representing territory taken over by the British East India Company, with Oudh being the one last cheery waiting to be swallowed. All this backgrounder is no doubt useful, but it does give a rather forced tone to the proceedings, and it doesn’t address the precise relationship between the East India Company and the British Crown, which I suspect nowadays is a big unknown to most viewers.

Andrew Robinson (Satyajit Ray: The Inner Eye) and Darius Cooper (The Cinema of Satyajit Ray: Between Tradition and Modernity) have both detailed the distance Ray travelled in his screenplay from Premchand’s original 1924 short story. Premchand’s tale focuses centrally on the chess obsession of the two nawabs (aristocrats) Meer and Mirza and is critical and censorious of the decadent self-centred society that they represent. Ray has expanded on these two central protagonists by adding parallel scenes of the royal court and, most significantly, of Oudh’s British Resident (the East India Company’s representative, wielding considerable power) General Outram, played by Richard Attenborough in a rather strained and not entirely successful performance.

The scenes with Outram are the means by which Ray introduces the British perspective, their criticism of the king as an effete and irresponsible ruler, their machinations to effect the takeover of the kingdom, and their simple lack of comprehension of the virtues that Wajid Ali Shah may have. The latter features most prominently in an early scene when Outram quizzes his adjutant Captain Weston on the character of the king, and Weston details the poetry, the songs, the dances, the operas, and the concubines; “rather a special kind” of king, Weston concludes, to which Outram responds: “I’d have said a bad king. A frivolous, effeminate, irresponsible, worthless king.”

Ray doesn’t deny the negative features of Wajid Ali Shah’s personality, nor his shared responsibility for the loss of his kingdom to the British, but he doesn’t make the king the target of any kind of explicit political/historical critique either. Similarly, the nawabs Meer and Mirza, whose chess obsession at best diverts them from and at worst blinds them to the realities of both their domestic lives and the political events in the outside world, are treated with a certain ironic sympathy. This is only to be expected from the director of The Music Room. In that film Ray clearly showed both the necessity for the zamindar way of life to pass on and at the same time a regret for the aesthetic virtues that would be lost through that passing.

As far as The Chess Players is concerned, Ray himself talked about “a certain ambivalence of attitude” and added:

I didn’t see Shatranj as a story where one would openly take sides and take a stand. I saw it more as a contemplative, though unsparing view of the clash of two cultures—one effete and ineffectual and the other vigorous and malignant. I also took into account the many half-shades that lie in between these two extremes of the spectrum… You have to read this film between the lines.

To be honest, The Chess Players doesn’t quite live up to the depth of characterisation that Ray promises here. Certainly, he doesn’t offer a one-dimensional critique of either the British or the Oudh aristocracy, but the premise underlying the film of the parallels between the private chess games and the political machinations taking place simultaneously is rather obvious, the characters are flat, and there are problems of tone—in particular, the documentary voiceover and the animation seem out of keeping with the rest of the film, and Ray also doesn’t appear comfortable with the coarser, more farcical aspects to his script. In the end, this is a minor Ray film.

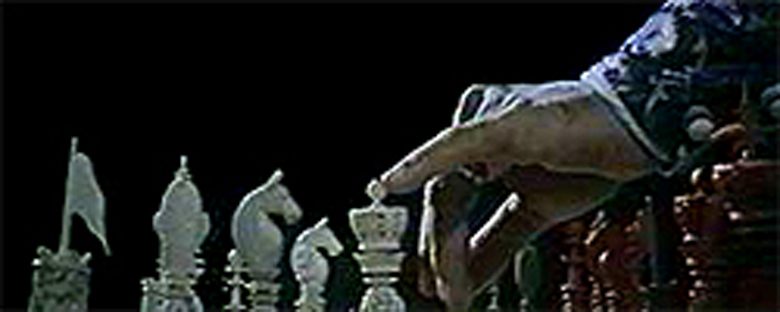

For all the historical backgrounding and the parallel story of the political events around Wajid Ali Shah and General Outram, the focus of The Chess Players is on the two friends, Meer and Mirza, and their chess games. The very first shot is a close-up of the pieces of an Indian chessboard, white lined up on the left, bright-red on the right, against a background of dark black filling up most of the screen. Slowly, deliberately, one richly-costumed arm moves from the right into the frame to move a piece, followed by another doing the same from the left. This is our introduction to Meer and Mirza (as the narrator sets the ironic tone with his “Look at the hands of the mighty generals deploying their forces on the battlefield”), and the way the chess players themselves are outside the shot establishes how the chess game is built on the exclusion of the off-screen. This exclusion is a political one, Meer and Mirza’s blindness to and/or denial of the historical events they are in the middle of, but it operates first on the level of their private, personal lives.

Both men’s wives are neglected in their all-consuming obsession with the chess game. Mirza’s wife is jealous and frustrated and tries luring him away in the middle of one of the games, attempts but fails to seduce him, and subsequently steals the chess pieces—which the players simply replace with other objects. But the distractions are too great, so the game moves to Meer’s house, where a sex farce is played out as Meer discovers his wife’s young lover under the bed without being able to “read” what this means; just as they’re not “reading” what’s happening in the world outside. For these men the chess game is an emasculating activity—Mirza is effectively rendered impotent, Meer is cuckolded—with clear parallels with the king and his obsessions and neglect of his princely duties. But just as with the king, there’s a clear sense that the two friends’ devotion to their game appeals to the aesthete in Ray.

As the historical forces at play start to impinge on their world, the two friends make their escape outside the city in order to continue their game in peace. But Mirza’s loss of this game played out in the rural peace and quiet leads him to take his revenge by revealing to Meer his wife’s adultery. Meer pulls out a pistol and at the moment a young local boy announces “The British are coming!” fires, the bullet piercing the edge of Mirza’s cloak. This act of violence is a comic, parodic reflection of the lack of resistance which takes place in the wider world; for Wajid Ali Shah has disarmed his own troops and the British are walking in, unopposed.

When Meer returns, chastened, he can only comment, “The British take over Oudh while we hide in a village and fight over petty things.” Both of them now acknowledge their pathetic situation, their weakness and indolence, yet they also indulge in it, while now adjusting themselves to the new realities. “Let’s have a fast game,” suggests Mirza, and what they turn to now is the British version of the game which had shocked the two nawabs when they were told about it earlier in the film. The takeover is complete, and the film leaves us with the image of these two impotent figures sitting alone in the shade of the tree, ineffectively swatting at the mosquitoes, and continuing on with their game of chess—British, and not Indian chess.

We don’t do comments anymore, but you may contact us here or find us on Twitter or Facebook.