Reviews

John Cassavetes

USA, 1968

Credits

Review by Chet Mellema

Posted on 07 March 2008

Source The Criterion Collection DVD

Related articles

Reviews Husbands by Teddy

At the beginning of John Cassavetes’ Faces, the viewer follows Richard Forst, an aged and somewhat apathetic high-ranking executive of a powerful investment firm, into a film screening room where he is pampered by three female assistants. The level of servitude is almost embarrassing—at one point an assistant literally puts a cigarette in his mouth, lights it, and then removes it at his command, all without the executive lifting a finger. Forst’s ego is suffocating, yet his assistants treat the procedure as necessary—they’ve been through it many times. The executive is soon joined in the screening room by a kettle of the film’s backers and an elderly, skeptical investor who asks, “What are you going to sell us this time?” to which she receives the simple reply, “Money, of course.” The viewer is witnessing the shameless commodification of film and an absurd coddling to potential investors all too prevalent in 1960s Hollywood. The pitch continues as the salesmen describe the film they are about to screen with asinine taglines like “the Dolce Vita of the commercial field … but not a crude film,” and “an impressionistic document that shocks.” They understand that art cinema without qualifiers like “but not a crude film” will not sell. Hearing enough talk, Forst commands that they get on with the screening and the lights go down.

Cassavetes holds nothing back in the opening scene of Faces. It is certainly a mockery of the Hollywood studio system and the soulless control it wields over the filmmaker. The cynicism and conversational detail prevalent in this scene lead to a credible assumption that it is at least somewhat autobiographical. And if not a verbatim recreation of Cassavetes’ experiences with Hollywood, it is no stretch of the imagination that such screenings and ridiculous pitches were common occurrences in the 1960s, if not today. It is also possible to read the opening scene as a sarcastic wink from Cassavetes to his supporters, at least those who admire a principled and independent manner of filmmaking and believe in cinema as an art rather than a commodity. In that regard, the scene takes on a comedic tone, especially in the qualifications used to describe the film and pacify the investors prior to the screening. These guys just don’t get it.

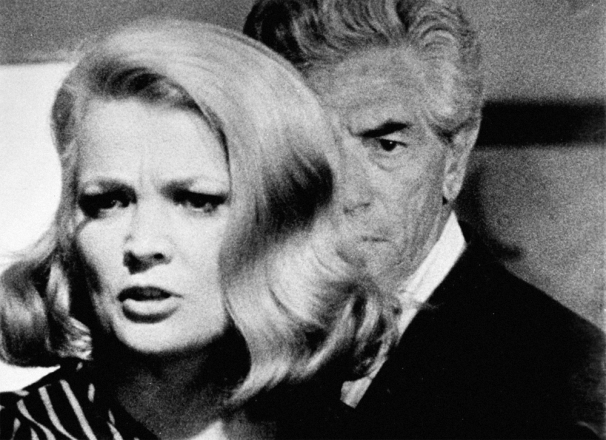

This opening scene is, however, more than just a thumb-of-the-nose at studios and financiers. It is an emphatic announcement to the viewer that this film is breaking from preconceived limitations in every way. Cassavetes intentionally employs an unpolished and grainy, black and white photography that presents a startling contrast to the glossy and sophisticated look of conventional studio films, especially in 1968. Nevertheless, Faces’ calculated ugliness produces an almost unmatched and inexplicably realistic beauty. This effect can be partially explained by the utilization of virtually unknown or first-time actors who, with the exception of Gena Rowlands (Jeannie) and perhaps Lynn Carlin (Maria Forst), would never be hired for their looks. The everyman appearance and qualities of each actor floods Faces with a realism undoubtedly ill-preferred by the mainstream. It’s too real to be escapist entertainment: we know these faces, people, conversations, and blemishes.

The film’s most defining characteristics are the constant employment of its actors’ wonderfully imperfect faces in close-up and the seemingly haphazard composition of its shots. Cassavetes understands that the lives of the people in the film are of greatest importance. As a result, each scene makes use of an extraordinary number of close-ups. The overall narrative and meanings to be gleaned from the film arise from the physical eccentricities, glances, and various nonverbal expressions found on or suggested by each actor’s face, as opposed to some arbitrary plot. I can recall no other film that so effectively tells its story through the idiosyncrasies and emotive faces of its actors.

Similarly, to stress the importance of the lives of those inhabiting Faces, Cassavetes uses a lively camera to relentlessly follow his actors everywhere—inside, outside, through hallways, up and down staircases. Little attention is given to whether the actors “hit their mark” or if the camera drifts slightly in and out of focus. Rather, the actors are given a chance to breathe and develop scenes organically. A pointed example of this technique is when Dickie (that is, Richard) and Freddie, business colleagues and old friends, playfully sing and dance for Jeannie at her apartment. The two men begin by taking turns flirting with and inconspicuously propositioning Jeannie, but when Freddie realizes he is the odd man out, the feel of the scene drastically changes from lighthearted to one of anger and melancholy. Cassavetes captures the action with a handheld camera—paying little attention to whether the actors are in perfect focus, or if the lighting is just right—that permits the audience up-close and unfettered access to the emotional development and mood swings of the characters. As a result of this and similar scenes, Faces conveys a genuine sense of pleasure in creation and the creative process. But the improvisational feel of the film clearly comes at the cost of painstaking deliberation. Making something appear improvised and “real” is much harder than replicating the melodramatic contrivances that audiences generally associate with cinematic “realism.” Shooting from behind furniture, partially obscuring actors with various objects in the room or other people, and a stubborn reliance on diegetic lighting, all allow Cassavetes to inject Faces with a fly-on-the-wall sensation that adds to the “too real to be entertainment” feel of the film. The effect is truly remarkable.

Faces takes place during one California evening and night, centering on the rapidly disintegrating marriage of Richard and Maria Forst. As Richard finds fleeting companionship with Jeannie, a prostitute, Maria and her troupe of housewives seek youthful revival at a dance club and are escorted home by Chet, a young hustler. Through seductions, infidelities, and lasting uncertainties, Richard and Maria find themselves at a crossroads. Notwithstanding these generic details of its plot, Faces is about communication, and notably the lack of communication existing in middle class marriages. The film’s characters, especially Richard and Maria, completely lack the faculties and earnest desire to effectively communicate with one another. Their conversations and interactions are littered with juvenile jokes, veiled laughter, and superficial advances in the form of, for example, dancing or banal small talk. Early in the film they giggle and romp their way through a conversation made up entirely of tongue twisters and non sequiturs, acting as relationally content as ever. Moments later, however, Richard is demanding a divorce—obviously a disconnect exists in the lines of communication. Perhaps they think they are engaging in meaningful discourse and effective communication but lack the awareness necessary to see past their own façades. They are only fooling themselves. Cassavetes’ script expertly captures his characters’ inabilities through plentiful, but entirely empty dialogue, like trading tongue twisters and other stale attempts at conversation. There is a lot of talk, but no one is talking. On the contrary, everyone seems to be playing the roles—or wearing the masks, if you will—established by their comfortable but unfulfilling relationships and societal positions.

So when a character removes his mask or steps out of her comfort zone with pointed, dramatic interaction, the effect is shocking not only for the other characters in the scene, but also for the viewer. When Dickie returns to Jeannie’s apartment later in the evening, a man named Jim has invaded his territory with desires on Jeannie’s companionship for the evening. Cassavetes allows the tension between the two lusting males to slowly build, each bolstering his position by reciting his attributes and social standing, only to be abruptly pierced by Dickie’s eventual domination. And immediately following declaration of the winner, we are witness to one of the quickest feud-turned-friendship scenarios I can recall. Within the scope of one scene we feel suffocating tension, a burst of genuine emotion, and a return to normalcy that is more of a veiled truce than mature progress. The genius of Faces lies in Cassavetes’ ability to slowly lull his characters in such scenes—and therefore the audience—into an extended, pleasant sense of ease before pulling out the rug. He structures Faces around these showstoppers and at least one such example can be found in each extended sequence of the film. Their shocking effect acts as a slap in the face to the previously impotent interactions and cumulatively underscores the need we all share for sincere communication with others.

Another notable aspect of Faces is the devastating vulnerability continuously conveyed by its characters. Months and years of faux-communication have drained these individuals of their self-confidence and replaced it with debilitating insecurities. Almost every character in Faces is achingly desperate for attention. While not all such sentiments are expressed overtly, underneath the masks and behind the roles exist real and pitiable despondencies. Quite possibly the best example of this forlorn and frantic desire for attention is displayed by Maria’s friend Florence, an older housewife with a crush on Chet. After making a series of inebriated advances on the younger man, Florence simply solicits a kiss, but does so with a naked despair that cries out for empathy. After he momentarily eases her pain, Florence asks for a ride home, realizing the fantasy has passed. I find it difficult to feel anything but sadness during Florence’s solicitation and its aftermath. She likely experienced a moment of fleeting euphoria, yet the distressing realization of what lies ahead for Florence quickly saps the moment of any lasting joy. While Florence openly displays her vulnerability, most of the other characters remain realistically guarded. Nonetheless, with a careful and discerning eye, the nuances and subtleties in each character’s facial expressions, glances and body language—expertly captured by Cassavetes’ close-up and wandering camera techniques—reveal more about their weaknesses and insecurities than they would otherwise willingly share.

In highlighting the characters’ perpetual inability to communicate and this masked but boiling vulnerability, Cassavetes has fashioned in Faces a film that confronts frighteningly genuine problems. It addresses age-old maxims in a truly inimitable style described perhaps as intentionally artless art. However one may choose to interpret Cassavetes’ film, it provides a rewarding moviegoing experience, one with no easy answers and a dependency on the subjective views of each audience member. The final shot of the film is an illustration of such dependency on the subjectivity of the viewer, as it finds Richard and Maria seated on the interior staircase of their home on the morning after a series of unforgettable and lamentable events. They are facing opposite directions and near opposite ends of the stairs. While the characters head off in different directions as the film concludes—Richard heads down toward the kitchen and Maria up to the bedroom—the anger and disdain from the previous evening seem to have eroded slightly. An ambiguity exists as to whether this erosion is the result of an acceptance of the inevitable end of their marriage, or a silent acknowledgment, one to the other, that each has made a mistake. The answer may lie in the individual cynicism or optimism of the viewer, but even an optimistic interpretation could not predict a sudden ability to communicate or a renewed sense of self-confidence for these despondent characters.

We don’t do comments anymore, but you may contact us here or find us on Twitter or Facebook.