Reviews

She Let Him Continue

Noel Black

USA, 1968

Credits

Review by Victoria Large

Posted on 09 September 2013

Source 20th Century Fox DVD

Well into the twentieth century, the Nashua River, which runs through central Massachusetts and up to New Hampshire, used to change color. The paper mills along its shores polluted it with dyes, and one can still search online and find surreal images of the river running red. My mother, who grew up in the area, still talks about the once commonplace sight of the Nashua’s unnaturally colored waters. Director Noel Black artfully toys with the image of the polluted river in 1968’s Pretty Poison, which was filmed along the Hoosic and Housatonic Rivers in western Massachusetts, but seems to take inspiration from the dye-laden Nashua. The imagery is apt when it comes to the film’s appealingly toxic storyline, which follows Dennis Pitt, a thirtysomething man attempting to rebuild his life after years of psychiatric institutionalization. Dennis secures a job at a riverside chemical plant that routinely discharges red liquid waste into the nearby water, anticipating and underscoring the bloodshed that soon disrupts his return to the outside world.

Black’s underrated work feels like nothing so much as the missing link between Psycho and Heathers: it stars Anthony Perkins, just eight years removed from his initial turn as Norman Bates, as the disturbed, yet somehow sympathetic, Dennis, who begins obsessing over a high school girl named Sue Ann. He eventually makes contact with her, claiming he’s from the CIA and needs her help for a secret operation. Dennis has some trouble distinguishing fantasy from reality, which makes it a little difficult to determine how much he believes his own lies, but he ultimately seems pretty well aware that he’s putting Sue Ann on. But when Dennis’ roleplaying fantasy gets out of hand — and people start dying — Sue Ann appears much too at-ease with the developments. “You’re sweating,” she says to Dennis as they stand over a victim. “You’re cool,” he replies. It becomes unclear who is playing who, and since we know from the outset that our protagonist is lying about (and perhaps to) himself, it’s difficult to place our trust in any of the characters.

Forty-five years after Pretty Poison’s release, it’s still a deeply disconcerting picture, in part because of its perverse, and very dry, sense of humor. The stereotypically girly trappings of Sue Ann’s bedroom, including a poster of ballerinas, stand in ironic contrast to the film’s murderous plot twists, and Tuesday Weld invests the character with just the right level of teenage ennui and offhand cruelty. For instance, just after Sue Ann and Dennis have sex for the first time, Weld finds just the right indifferent tone in which to ask, “When can we do something exciting?” Perkins also proves adept at handling the film’s deadpan style, such as when Dennis quips that the reason he reports to a parole officer is because he once performed “unlicensed tree surgery.” This is the type of movie where murder confessions are so awkwardly executed that they become comic. It generates genuine laughs, but uncomfortable ones.

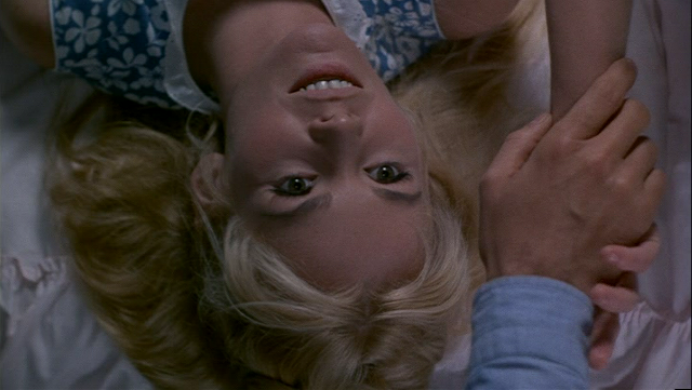

Black also creates a squirmy, voyeuristic atmosphere, framing Perkins and Weld in tight two-shots that make the viewer feel like an intruder, and favoring intense close-ups that nearly break the fourth wall. Other shots demand that we peer past various obstructions in order to see the characters. Like Peeping Toms, we watch through tree branches and dirty windows, from behind a row of drinking glasses or a police car’s protective barrier. These subtle touches create an illicit atmosphere, implicating us in the depravity onscreen. Small wonder that when a character raises a gun during a climactic scene, it appears to be trained on the audience.

Pretty Poison’s daring approach will perhaps always limit its appeal, but it has never quite gone away, lingering on the minds of film lovers much as the brightly hued Nashua River has never quite left my mother’s memory bank. And the film has aged well, with cryptic, repeated cutaway scenes that would be at-home in a modern production, and a tone that’s bound to resonate with cinephiles who long ago embraced the Coen brothers and David Lynch. It’s self-aware but not smug: there’s a scene that’s highly reminiscent of Psycho’s post-murder clean-up sequence, but this time there’s a couple involved, and they start bickering about the process. Too many films are timid in execution or overly enamored of their own cleverness. Pretty Poison has neither problem: it’s brilliant, biting, and never labored.

We don’t do comments anymore, but you may contact us here or find us on Twitter or Facebook.