Credits

Feature by: Rumsey Taylor, Tina Hassannia, Leo Goldsmith, Thomas Scalzo, Steve Macfarlane, David Carter, Adam Balz, Sam Bett, and Matthew Derby

Posted on: 01 February 2013

External links:

I. Fossils

Repeat compulsion, that old workhorse of the psychology business, sees a patient experiencing the same trauma ad nauseam until it either dulls itself down or grows to dominate his entire life. How else, then, to introduce the Godzilla franchise, which has permitted nearly six decades’ worth of Japanese movie lovers – mostly children – to witness the obliteration of Tokyo over and over again? Godzilla – or, by his original name, Gojira, a portmanteau of the Japanese words for “whale” and “gorilla” – was originally a sharply polemical response to American militarism during and after World War II. The beast was conceived by Ishirō Honda, director of the monster’s 1954 debut and godfather of the kaiju (giant monster) genre, who spent the War’s last year as a prisoner of the Chinese. Legend has it that he was driven through the firebombed ruins of Tokyo, agog at the vastness of its devastation. As a response to such an atrocity, the images in Godzilla didn’t just evoke the ashes of Japan’s great cities, they replicated them on a harrowingly convincing scale.

Following the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the United States had specific plans for Japanese industrial power. Eisenhower’s “atoms for peace” policy was both an economic cudgel against Soviet expansionism and a tacitly cruel reminder of the putatively benevolent Americans’ bottom line: effectively, atoms or war. 1954 was a critical year for selling the program in Japan, but popular backlash played no small part in Godzilla’s phenomenal success. Just as the arch-conservative new parliament began budgeting for reactor contracts with companies like General Dynamics, a U.S. bomb test in the Pacific eclipsed a Japanese fishing boat – the Lucky Dragon #5 – and contaminated both the fishermen and the fish. One radio operator died. By the time it arrived back at the mainland, press had called the event “the second atomic bombing of Japan.”

The tragedy laid ground for what became, in effect, the worldwide anti-nuclear movement, which accordingly fed into the anti-Vietnam movement and May ‘68. An appeal begun by some housewives in the Suginami section of Tokyo would ultimately see 32 million citizens – one-third of the population – petitioning against the hydrogen bomb. For both leftists and nationalists, atomic energy was seen as the vanishing point for postwar obsequiousness, a Faustian gamble that could easily see another mushroom cloud over another Japanese city. The iron was hot: eight months after the Lucky Dragon #5, Honda’s cameras were rolling on the Toho soundstages. The film would open, accordingly, with a retelling of the Lucky Dragon #5 tragedy, only the A-bomb test at the film’s beginning irradiates something in addition to the ill-fated fishing vessel: a long-forgotten prehistoric behemoth.

Sketching the sometimes contradictory political landscape of 1950s Japan, Shoriki Matsutaro demands mention. An ex-cop, accused war criminal, and “father” of both Japanese baseball and the country’s largest news conglomerate, Shoriki did more than any other individual player in government to ingratiate the Japanese public as to the promise of nuclear power. Both the top man at the Yoimuri Shimbun – the Japanese equivalent of The New York Times – and first president of the Japanese Atomic Energy Commission, Shoriki blueprinted a campaign to erode public skepticism. Widely speculated to have been on the CIA payroll, he held a massively publicized shinto purification ceremony to “welcome the atom back to Japan” in 1955. Some politicians still clung to the dream of a Japanese bomb, but by and large the “Peaceful Use Of Nuclear Energy” tour worked miracles for public opinion by triangulating atomic energy with fiscal strength and a return to political sovereignty. A hundred thousand spectators turned out to see Shoriki proudly announce that Japan’s first reactor would be up and running by 1956—in Hiroshima.

II. “It’s Godzillaaaaaa!”

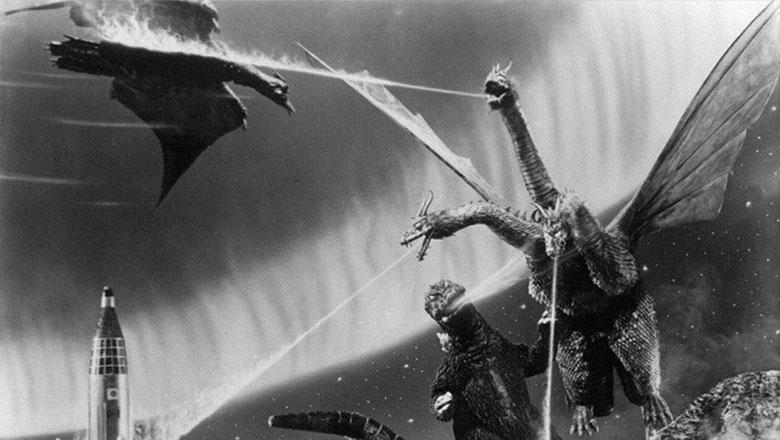

All of this is to say the success of the first Godzilla movie simply would not have been possible in 1953 or 1955. A comparatively weak sequel was churned out in a rush, whereby Godzilla, once an unstoppable force of terror slaughtering innocent Japanese right and left, returned instead as something of an industrial nuisance, blacking out Osaka until a valiant fleet of former fighter pilots dispatch him by burying him under an ice glacier. The film introduced his quadruped ally/enemy Angilas, and ushered in the golden era of lumbering monsters and bitter “versus” deathmatches. The carnage and destruction that gave the original Godzilla its edge over its American drive-in counterparts vanished. This generation was weaned on space exploration, superhero comics and saturday morning cartoons; there was so much money in kaiju pictures that Hondas became patently anti-ideological. At their best, his films from this period – including Matango, Mothra, The Mysterians, Invasion of Astro-Monster and Destroy All Monsters – are genre masterpieces, streamlined modernist sci-fi tales that never once grasp at verisimilitude.

Everyone knows Godzilla; few have actually engaged with the films on their own terms. Most predicate on whether or not a (slightly dopey) Japanese man, working for some interchangeable authority (universities, newspapers, the U.N.), can get the girl while both avoid being crushed by falling rubble. The potency of the series’ violence is strictly monster-on-monster; if seeing Godzilla melt a battalion of tanks like plastic was horrifying for audiences in 1954, it was eliciting squeals of delight by 1962. Humans in costumes played space aliens disguised as humans, piloting mind-controlled gargantuas with x-ray power and candy-colored rocket ships. The reputation that haunts the franchise as a string of quintessentially “bad movies” really starts here, but the aversion has just as much to do with the films’ U.S. distribution.

En route to American shores, more than one of the scripts was painted over with infamously awful dubs featuring actors from New England (mutating “Gojira” again, this time into “Godziller”) and simplifying the dialogue—turning the Japanese protagonists into childlike simpletons. But self-flattering as the Americans’ disdain may have been, it’s not entirely without merit. The showa (1954-1975) period of movies reached its camp summit in the early-to-mid 1970s, when Toho was making them ever-cheaper. The aesthetic went rancid: flat, telephoto closeups of rubbery masks with shrieking noises slathered on in postproduction; the eternal snap zoom; hours of slo-mo explosions; tireless, sluggish wrestling matches. With a newfound goofy countenance, Godzilla danced, talked (in roars, with translation), used his fire breath as an ad hoc jetpack, and shook hands with opponents after a fight. At least a half dozen battles take place on the same roughshod desert backdrop, apparently to minimize civilian casualties (or new set construction.) The music switched from Akira Ifukube’s stern classical marches to Masaru Satō’s brassy rhumbas.

For better or for worse, Godzilla had been infantilized – but these movies are not without their own charms. Jun Fukuda’s abundantly silly Godzilla vs. Mechagodzilla (1974) opens with a stately, languorous tracking shot along a mountain range to reveal the spike-plated Angilas emerging from a fog on all fours, roaring triumphantly. The film is the monster’s last in the series, before he’s brutally murdered by Mechagodzilla (disguised as his ally, Godzilla). The funereal majesty of his introduction reveals much about the genre; kaiju films would always exist as mere plastic wrappers for their outsized creatures, unlikely to frighten anyone older than a toddler but commanding their own bizarre form of respect—foam-rubber deities blown up to restore balance to the planet as it’s imagined onscreen. Nevertheless, the gimmick got old, and Toho closed up shop after Ishiro Honda’s final film, the underperforming, recycled-footage-heavy Terror of Mechagodzilla (1975).

III. Girth Crisis

Ten long years passed before the brand was revitalized for Return of Godzilla in 1984. The entire history of the 60s and 70s vanished; for the first of several times, Godzilla’s lineage went straight back to 1954. Pitting the monster up against a modern Japan, the film ambitiously recast Godzilla as a fearsome villain, a scourge of the “rising” economy who betrayed its nuclear secrets. Maybe more so than any Godzilla film since the first, Return played it straight—and reaped dividends. His look had been updated to make him bulkier, fiercer and more evil-looking, but tracing the monster’s path over the next ten years points inevitably back to the same trend: by the time the heisei saga ended in 1995, Godzilla was half animal, and half cuddly superhero. Each title in the 90s era was a bigger and bigger juggernaut of a movie event, engineered to perform a kind of economic shock therapy on Godzilla’s box office.

These films complicated the mythology in epic fashion: Godzilla vs. Biollante created a strong, haunting new villain who was herself part-Godzilla; Godzilla vs. King Ghidorah established a new origin for the monster, dating back to a revenant dinosaur on remote island during World War II, who attacks a platoon of American soldiers on its beaches—including a “Private Spielberg.” Mothra, Mechagodzilla and Rodan were all reintroduced, plus an adorable five-foot baby Godzilla. The robot nemesis idea was updated in Godzilla vs. Mechagodzilla; instead of an alien threat, Mechagodzilla was human-piloted by members of the Earth Defense Force – EDF – an ever-expanding unit specifically intended to deter giant monster attacks under the aegis of the United Nations. By 1994’s Godzilla vs. SpaceGodzilla, the same team of “Earth Defense Force” soldiers were piloting the M.O.G.U.E.R.A., a 400 foot robot-kaiju that disassembles and reconstitutes itself depending on the task at hand.

It’s impossible to fully examine the franchise without speculating on the EDF. A mix of spies, paleontologists and elite commandos, there can be little doubt that the team – which proudly unveiled a new vehicle/weapon/monster of its own with each new installment – is intended as a kind of military salve on the Japanese conscience; expensive propaganda for combat missions that can’t actually happen. The launching of the EX-1, a generic-looking warship piloted by a stone-faced young cadet in Godzilla vs. Biollante, is buttressed by solemn strings more appropriate to, again, a war film. Almost like accidental satire, the series spun wildly out of control, each installment more bizarre, hyped, and expensive than the last despite diminishing returns. The baby Godzilla grew over two more movies, until the remarkably cynical “last” heisei film, Godzilla vs. Destoroyah. By then, the baby has become a ferocious, forest-green teenager, exploited by the government to lure Godzilla into Tokyo, whereby Destoroyah can kill him and prevent his heart from having an atomic meltdown.

IV. Reverberations

Whether or not Godzilla “died” in 1995 to clear the way for Roland Emmerich’s 1998 Americanization, or because the Japanese series wasn’t lucrative anymore, remains a mystery. The Japanese fan community’s disheartened response to Sony’s Godzilla jumpstarted the most recent act in the franchise, Toho’s “Millennium” sequence that lasted from 1999 to 2004. These films betray an attendant despair: Godzilla appears less onscreen than ever before, with screen time doled out to other monsters but also to the young cadets of the EDF—kaiju as backdrop for Matrix-influenced human action movies. Godzilla’s final sendoff, Final Wars, has the frenetic quality of a video game interstitial designed to fulfill contractual appearance obligations (for monsters) and toggle the fans’ sweet spots within constraints of time and budget, before Godzilla (and, once again, baby) trot off into the sunset at the other end of the Toho water tank. In its farewell, the series had become what its detractors always accused it of being—sloppy.

Looking across the 28-title filmography, the sheer repetition of the phrase “Godzilla vs. X” predicts the big reptile’s victory at the end of almost every match—and indeed, unlike the atom, Godzilla is pretty predictable. Monsters changed, but the format – down to specific shots and moments – has remained more or less the same. The bout of post-9/11 kaiju blockbusters from Hollywood (particularly Cloverfield and Michael Bay’s Transformers trilogy) are contingent on the idea that U.S. filmmakers are getting better at imagining the unimaginable than ever before. But these are speculative exercises at best. (Sure enough, another American Godzilla reboot is due to start shooting in Hawaii next month.) All we can deduce from the bloodshot eyes and craggy skin of Godzilla – and his epochal softening-up – is that the same kind of apocalypse being dreamed up in Hollywood today has haunted Japan for nearly sixty years. Life, mutation, death, rebirth and life again: whether you consider junk CGI an improvement over junk pyrotechnics is just a matter of taste.

Throughout February, we will post reviews of each Godzilla film. Please refer to this page for updates throughout the month.

Introduction by Steve Macfarlane

By Rumsey Taylor, Tina Hassannia, Leo Goldsmith, Thomas Scalzo, Steve Macfarlane, David Carter, Adam Balz, Sam Bett, and Matthew Derby ©2013 NotComing.com

Reviews

-

Godzilla

1954 -

Godzilla Raids Again

1955 -

King Kong vs. Godzilla

1962 -

Mothra vs. Godzilla

1964 -

Ghidorah, the Three-Headed Monster

1964 -

Invasion of Astro-Monster

1965 -

Ebirah, Horror of the Deep

1966 -

Son of Godzilla

1967 -

Destroy All Monsters!

1968 -

All Monsters Attack

1969 -

Godzilla Vs. Hedorah

1971 -

Godzilla vs. Gigan

1972 -

Godzilla vs. Megalon

1973 -

Godzilla vs. Mechagodzilla

1974 -

Terror of Mechagodzilla

1975 -

The Return of Godzilla

1984 -

Godzilla vs. Biollante

1989 -

Godzilla vs. King Ghidorah

1991 -

Godzilla vs. Mothra

1992 -

Godzilla vs. Mechagodzilla

1993 -

Godzilla vs. SpaceGodzilla

1994 -

Godzilla vs. Destoroyah

1995 -

Godzilla 2000

1999 -

Godzilla vs. Megaguirus

2000 -

Godzilla, Mothra and King Ghidorah: Giant Monsters All-Out Attack

2001 -

Godzilla Against Mechagodzilla

2002 -

Godzilla: Tokyo S.O.S.

2003 -

Godzilla: Final Wars

2004

We don’t do comments anymore, but you may contact us here or find us on Twitter or Facebook.