Reviews

Ying hung boon sik / True Colors of a Hero

John Woo

Hong Kong, 1986

Credits

Review by Rumsey Taylor

Posted on 24 July 2012

Source Ais BRD

Categories John Woo’s Hong Kong

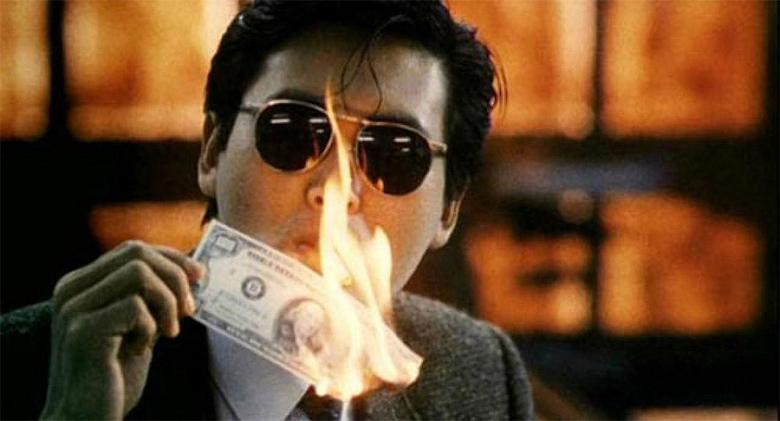

Mark Lee is characterized by a cherubic grin, which invariably sits beneath a pair of gold-rimmed Ray-Bans. It befits his job as a gangster, italicizing his nefarious interactions - particularly, exchanging briefcases full of counterfeit U.S. bills for authentic Chinese currency - and depriving them of any sinisterness. His partner, Ho, is more solemn. His receding hairline suggests more wear in his experience, and when he smiles his face strains into a network of wrinkles. Of this pair, one represents the prestige of a capitalistic triad, and the other its debilitating personal expense.

Ho’s constant forlornness isn’t solely the result of his experience, however. The only time he’s genuinely relaxed is when he’s in the presence of his younger brother, Kit, a well-to-do chap unadulterated by the responsibility and suspense Ho faces on a regular basis. Kit, as it so happens, is also in a police academy, and has no knowledge of his brother’s affiliation with the criminal underground. Ho’s anxiety is exacerbated by this, in deceiving his brother for the purpose of maintaining their family’s goodwill.

A Better Tomorrow is initially distinguished by this pair of contrasts: between Ho and his younger brother, and between Ho and his more chameleonic partner, Mark. Ho personifies the tension between Mark’s life of crime and Kit’s earnest endeavor to repress the same. But being as he has a pronounced allegiance to both men, and until he’s in the party of both late in the film, his anxiety burgeons.

Ho resolves to come clean, promising his employer one final job before he retires, and disabling any possibility that his brother will discover his awful truth. He relays this plan to his bedridden father, who recalls that the two used to play cop and thief when they were children. “I don’t want you to play the same game again,” the father laments, and Ho understands.

This is Ho’s better tomorrow: a future free of deception of those whom he values most. This endeavor is shortly compromised in absolute fashion, resulting in a three-year jail sentence and a brother, now a graduate of the police academy, in sudden and great moral opposition to him. Prior to Ho’s capture, the brothers’ father was attacked by a member of Ho’s gang, and Kit, in defending his elder, bears witness to his father’s revelatory final words, that he must forgive his brother.

A Better Tomorrow’s essential conflict apexes at this moment, and for the brothers their professional allegiance gives reason for their personal conflicts. Ho’s position is delicate, however, for he has access to the gang that has both deceived him and is to his brother unknowably powerful. The only recompense available to him, given that Kit harbors great distrust for him, is to disable the gang with which he was previously affiliated, and for Kit to perceive their conclusion as an elaborate apology. It is, for Ho, one commensurate with the severity of his deception.

This will come to the fray in a final shootout that finds Ho newly reteamed with Mark, and Kit in the middle of it all. The three are flanked on all sides by members of the triad, with whom they dispense in piecemeal but not without some cost. This climax is rendered with greater effect because at this point it is clear what’s at stake, and unlike other action movies in which the enterprise is contrived by greed or wrath, here the shootout seems a necessary if extremely uncertain hardship the practitioners do not desire. When they shoot at each other it is not with adrenaline-charged precision, but desperation, for they are posited against an oppressor so tremendous that it warrants the risk of their own lives.

This scene is populated by more people than I can reliably count, but it’s staged with clear iconography. The primary villain is outfitted head-to-toe in a white suit, and his henchmen are in all black. (This fashion’s dual purpose is clear once that white suit becomes covered in blood.) As the scene progresses it’s told in medium and wide shots, and the camerawork dollies about the premises fluidly. Only Ho and his compatriots are found in closeups, and these emphasize the moments between gunshots. Their faces are sweaty and bruised, their pupils distended as if in some attempt to review more of the dangerous periphery.

In his ensuing Hong Kong films, Woo’s shootouts would grow more elaborate, even cartoonish, but they’re nonetheless an expression of some sort of moral ultimatum. In some instances, the film’s moral narrative is forgivably undermined for these scenes’ exaggerated hallmarks. But this exaggeration describes the dramatic scenes as well. Kit, for example, has a new girlfriend whose niceties - as when she meets Ho for the first time - are quickly subverted by her shouty impatience, which is totally insensitive to the brothers’ reunion. And in their interactions, the brothers tease each other in a manner that’s almost homoerotic. This is not to mention the aforementioned thugs, who’ll flank their boss in a dart shape as if they’re migrating somewhere.

To draw attention to these things, however, is to deprive a John Woo movie of its playful spirit, and he employs these aspects as a means of advancing the principles of the narrative in shorthand. In A Better Tomorrow, the relationship between Ho, Kit, and Mark remains ever at the fore, and Woo’s later films would similarly pivot around some fraternal relationship. This describes his American films as well, even if they tend to be more propulsive action enterprises.

A Better Tomorrow was Woo’s first blockbuster in a career that’s spawned many around the globe. It is additionally his first collaboration with Chow Yun-fat, who would anchor his two most renowned Hong Kong films, The Killer and Hard Boiled (in the former film, it is Chow who’s outfitted in a discrepant white suit). All of Woo’s Hong Kong movies draw from the same palette, one demonstrated in its earliest mature form in this film: an unprecedented Asian blockbuster, and a catalyst for the great influence Woo would exert over the action genre in the years hence.

More John Woo’s Hong Kong

-

Heroes Shed No Tears

1986 -

A Better Tomorrow

1986 -

The Killer

1989 -

Bullet in the Head

1990 -

Once a Thief

1991 -

Hard Boiled

1992

We don’t do comments anymore, but you may contact us here or find us on Twitter or Facebook.