Reviews

Peter Neal

UK, 1970

Credits

Review by Tyler Wilcox

Posted on 09 December 2012

Source YouTube

Categories Rock Follies II

“What inspires your music?” asks the reporter in the opening minutes of the Incredible String Band’s lone foray into filmmaking, Be Glad For The Song Has No Ending.

“Oh … everything,” answers Mike Heron, one of the band’s founders, cosmically. “Everything.”

Coming from any other 60s musician, this might seem like the ultimate in shallow hippie-dippie sentiments. But more than many of their countercultural peers, the Incredible String Band could back such a statement up, and still cast a spell all these decades later. The ISB’s first LPs — from the self-titled debut to the double album masterpiece Wee Tam and The Big Huge — are stuffed with “the message of centuries rolling,” as one of their songs memorably puts it. At its best, the group conjured up a global village of the imagination, with room for a wide cast of mytho-historical characters. One of the ISB’s most powerful creations, “Maya,” sets Jesus, Hitler, Richard the Lion Heart, the Three Kings, Moses and Cleopatra, among many others, all in “the great ship of the world.” Blakean visions, puckish humor, universalist spiritual questing, Carroll-esque wordplay, gnostic philosophy — it all had a place in the Incredible String Band’s universe. You probably want to throw a healthy dose of hallucinogenic drugs in the mix too.

The ISB were canny sonic craftsmen as well, able to fit an astonishing range of multi-ethnic instrumentation and song forms into the grooves of their albums, fully utilizing the then-brand new multi-track recording technology of the day. In his recent, outstanding overview of British folk from Ralph Vaughn Williams to Talk Talk, Electric Eden, Rob Young writes that the group “captured [the] elemental essence of music as an intimate rite in the flickering light, imparting sacred mysteries to rapt ears in the sapphire deep of night.”

Still sounding hippie-dippie? Well, sure. The Incredible String Band was kind of the ultimate hippie band — though they famously bombed at Woodstock, their delicate acoustic ramblings wilting in front of the stardust masses. But as their inclusion in that festival’s bill suggests, they were also, weirdly enough, a commercially successful group for a time there, inspiring a devoted following and praise from the era’s ultimate tastemakers — the Beatles, the Rolling Stones and Bob Dylan. As the 60s drew to a close, the ISB had some money to burn. Hence, Be Glad For The Song Has No Ending.

All things considered, the 50-minute film (filmed in 1968, not completed until 1970) is not as self-indulgent as it might have been. Indeed, much of Be Glad is a straight documentary, featuring the band performing live and rehearsing, being interviewed, visiting exotic instrument makers, wandering in the forest and generally looking as though they’ve just stepped out of Tolkien’s Shire. Idyllic, pastoral images abound. The live footage is particularly good, capturing vital versions of classics like “Mercy, I Cry City,” “The Iron Stone,” and “Koeeoaddi There,” and showing off the group’s peculiar brand of onstage whimsy, with poetry readings, papier-maché masks, and stoned banter aplenty. “I’ve just been sent a letter that says we’re between Manitas de Plata and Jimi Hendrix,” Robin Williamson tells the audience. “Just so you know what you’re seeing.” The band members also prove themselves to be experts at the gnomic, Dylan-esque interview rejoinder. “How would you describe your songs?” asks an interviewer. “If I could describe my songs, I wouldn’t have to sing them,” answers Williamson, with only a trace of smugness.

Aside from the occasional random jump cut to some found footage, the opening sections of Be Glad For The Song Has No Ending wouldn’t be out of place in any BBC doc of the time. In fact, much of the film was originally filmed for the BBC’s Omnibus program, before the ISB hijacked their efforts with the elaborate fantasy sequence that takes up Be Glad’s latter section.

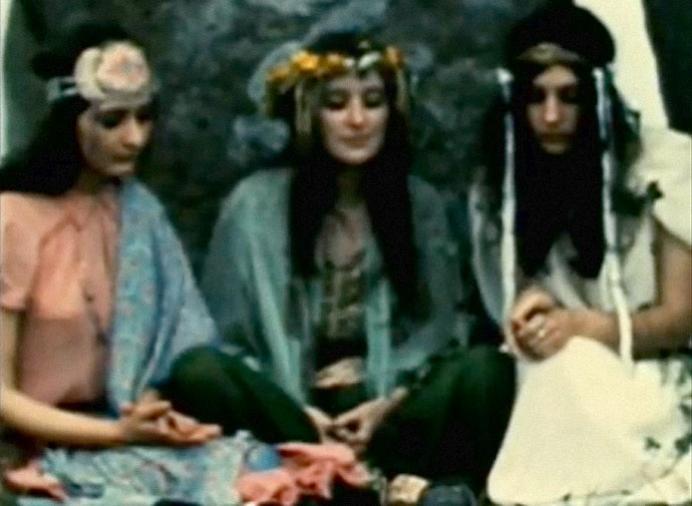

Entitled “The Pirate & The Crystal Ball: A Fable,” this is where Be Glad gets trippy. Filmed mostly on location at Pentre Ifan, a neolithic dolmen in western Wales, the sequence has a handmade feel that enhances the storybook, dreamlike qualities of the tale, The plot revolves around a pirate who comes into possession of a magic crystal ball, only to incur the wrath of a pair of woodland gods (played, perhaps not coincidentally, by Williamson and Heron). I think the pirate is then reincarnated in modern day England — but I might be wrong. Things get pretty psychedelic there at the end.

Your enjoyment of this 20-minute short film-within-a-film will depend on your tolerance for amateur Victorian theatrics, proto-Wicker Man pagan vibes, mystic maids, men dressed as turkeys and laughably bad fake facial hair. Apparently, my tolerance is extremely high. I find “The Pirate & The Crystal Ball” — and Be Glad For The Song Has No Ending as a whole — to be a charming and fairly successful cinematic representation of the Incredible String Band’s idiosyncratic vision.

More Rock Follies II

-

Big Money Rustlas

2010 -

Be Glad for the Song Has No Ending

1970 -

The Rutles: All You Need is Cash

1978 -

Cool As Ice

1991 -

Idlewild

2006 -

Masked and Anonymous

2002 -

Never Too Young to Die

1986 -

Leningrad Cowboys Go America

1989 -

Son of Dracula

1974 -

Under the Cherry Moon

1986 -

Purple Rain

1984 -

Graffiti Bridge

1990

We don’t do comments anymore, but you may contact us here or find us on Twitter or Facebook.