Reviews

La Invención de Cronos

Guillermo del Toro

Mexico, 1993

Credits

Review by Simon Augustine

Posted on 21 October 2008

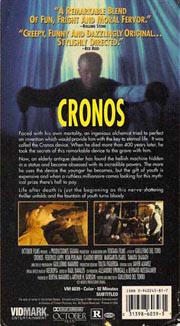

Source Vidmark Entertainment VHS

Categories 31 Days of Horror V

Watching a first or early effort by a filmmaker who later gains fame can provide fascinating insight into how he or she develops the technique and sensibility that appears in polished form in subsequent, more familiar works. I think of Duel, a TV film from the mid ‘70’s that stars Dennis Weaver as a motorist being terrorized by a faceless trucker relentlessly chasing him on the highway. It was the first feature-length film by a young Steven Spielberg, and remains one of the most famous made-for-television movies ever due to its ability to generate true suspense despite being confined to the small screen. A keen sense of how to build tension via music, editing, knowing what to show the audience, and perhaps more importantly, what not to show them, is present in Duel; a couple of years later this sense flourishes in Speilberg’s Jaws, a film comparable to Hitchcock in its emphasis on manipulation of audience instead of reliance on shock or gore. Another film that fits this bill is Dead Alive, a frenetic and ridiculously over the top gore-fest from the early ‘90’s that combines bloody thrills and an absurdist sense of humor—picture the Evil Dead films on steroids. It was made by a budding talent named Peter Jackson, who eventually raised the inventiveness and bravura use of special effects so on display in Dead Alive to spectacular heights in The Lord of the Rings epic. Whether we are interested as critics in how a director’s bag of tricks develops over time, or as filmmakers in tracing an aesthetic approach back to its inception, seeing these freshman efforts is a often a revealing and fruitful exercise.

Which brings me to Cronos, a pleasantly weird debut featuring a singularly odd take on the fountain of youth story. It was made fifteen years ago by Guillermo Del Toro, an auteur known today as a leading force in the fantasy/horror genre because of films like The Devil’s Backbone, Hellboy, and the critically beloved Pan’s Labyrinth. Del Toro is Mexico’s answer to Peter Jackson; along with a portly jocularity that belies a strident perfectionism and obsession with detail, both men rocketed to the stratosphere of fantasy cinema from humble beginnings and budgets based largely on fierce ingenuity. Cronos contains many elements found in del Toro’s later, popular successes: a passion for insectile subjects, in both their beauty and repulsiveness; sympathetic portrayals of young children caught in strange or horrible circumstances; and a renowned eye for the fantastical - in set and art design, creatures, and special effects - that sets him apart from the crowd. As a director he lends a mature, humane vision to a genre often lacking in those qualities, appealing to both old children and young adults. Albeit in germ form, these themes and tools begin to emerge to a measure of success in Cronos. It tells the story of an antique dealer named Jesus Gris, who runs a shop with his granddaughter by his side. Jesus comes across an unusual artifact hidden in the statue of an angel: a small golden orb the purpose of which is not immediately apparent.

The audience, however, knows (via a prologue) that it is the handiwork of a 14th century alchemist (isn’t it always?), who created “The Cronos Device” in order to give himself eternal life. Jesus unwittingly discovers its sinister modus operandi by fiddling with the thing. Suddenly, it “comes alive” and springs mechanical legs like a spider, gripping his hand. (It reminded me a bit of the puzzle-box in the Hellraiser series, another key to the supernatural accidentally awakened) Once attached, another leg emerges to pierce his skin, and before Jesus is able to break its grasp, it has drawn blood. Later, we learn it left behind a stinger, as if it were a metallic bee or wasp. In fact, Jesus has fallen victim to an infection of sorts, because following this first encounter, a bizarre relationship begins between Jesus and the device. He finds it frightening and repugnant, but is nonetheless seduced by the influence it wields, and allows it to “sting” him again, this time on the chest. The device quickly affects radical changes in his behavior: he feels youthful vigor (shaving off his moustache to look younger), and suddenly exhibits a renewed sexual energy and lust for life, as well as a disturbing craving for blood. It is as if he stumbled on a horribly attractive and dangerous drug of unknown origin, and is now made an addict. Jesus has tapped into, or perhaps been attacked by, a fountain of youth—but, as always, one that comes with a cost.

Unbeknownst to Jesus, a decrepit and eccentrically evil millionaire named De La Guardia has been relentlessly pursuing the life-extending powers of the Cronos Device in an attempt to ward off his own impending death. De La Guardia lives in a vast hideout that houses, among other things, his own harvested organs fermenting in huge glass jars, which are scientifically examined and partially consumed by their former host; and a huge replication (in progress) of the interior machinery of the Cronos Device, resembling the industrial guts of a factory or nuclear power plant. It’s a pretty freaky scene, to say the least. When De La Guardia dispatches his nephew and minion, a vicious lout played by Del Toro regular Ron Perlman to snatch the device from Jesus, a struggle ensues and the henchman murders the antique dealer. He is given a funeral and prepared for cremation by an overly casual undertaker in a sequence of gallows humor. But, infused by the power of the Cronos Device, Jesus rises from the dead and reunites with his granddaughter, who welcomes him back with complete acceptance and love, despite his unusual reappearance and rapidly deteriorating state. (These scenes effectively weave both comedy and moving sentiment into the horror tale, another trademark of Del Toro.) Together, they go to De La Guardia’s lair to seek revenge on the mastermind and his nephew. In the process of exacting justice, Jesus is ostensibly murdered again; yet, with the help of his granddaughter, is resuscitated a second time by the Cronos Device. After smashing the relic, Jesus finally escapes his vampiric hunger and artificial life, and dies peacefully in bed at home, for what we can only hope is the last time.

The bits involving the Cronos Device itself are Del Toro at his best, and most characteristic of the skill he exercises in future endeavors. The melding of mechanical instrument with organic, arachnid movements and actions easily holds sway over the imagination; a combination of machine and flesh, with tragic consequences, that is redolent of David Cronenberg’s best work. There is a recurring camera shot that goes inside the small device, showing us the cogs and wheels mysteriously producing the Cronos effect, which stands as the highlight of the film. It is obvious, from an audience’s perspective, that this view of the “engine” within the device is really a conventionally sized set built to simulate a miniaturized interior, but rather than detracting from the effect, the disparity in scale actually enhances our sense of wonder. The fact that a creative choice, which might otherwise have come off as merely a laughably bad special-effect, here plays like an aesthetic provocation tapping into a kind of magic realism, speaks to Del Toro’s skill. He instinctually knows the delicate line between, on the one hand, not revealing enough, which might leave us indifferent; and on the other, revealing too much, which might leave us incredulous, lightly amused, or bored. Somewhere between these two polarities is the conceptual location where a suitable and measured tension can, in the right hands, be exerted on the audience’s mind; one by which our natural spirit of inquiry is given just the sufficient amount of material to be inspired into working on its own behalf, extrapolating cues and filling in rightly-placed gaps and silences with a personalized, individual fancy. The greatest fantasy directors know how to gracefully touch this “sweet spot”—the secret is that they have confidence in the creative powers of the audience as well as their own; they are content to give our imaginations a chance to do some of the “heavy lifting.” As they say, what you imagine is behind the cellar door is usually much worse than what is actually there. A well-deployed game of perceptual hide-and-seek subtly enlists the viewer as an active participant, and culprit, in building the metaphysical elements of a story - always the most difficult to elicit: that is, a mood, an atmosphere, an ambience, the suggestion of concepts. It is also a primary tool for building suspense – “suspense” not only in the sense of leading us to a “gotcha” moment, but also in terms of a “suspension” of disbelief, By seducing the audience into contributing to its own fear, excitement, dread etc., a context is established that puts disbelief in a kind of mental parenthesis, making it easier to coax it into adopting, at least temporarily, the esoteric reality of the story. If a film is a conscious performance, then the mind watching becomes like a new sub-conscious; commenting and responding to the reality of the story in ways of which it is not even fully aware. Spielberg knows this, as does Jackson. And Del Toro can be confidently added to that list.

Call it the “Jack-In-The-Box Principle:” the skill of a director who knows precisely how much information to withhold (or distort), and how much to give away; i.e., the ability to frighten or bewilder or even awe an audience by not keeping Jack in his box too long (or too often), but also not letting him pop out too early - lest he lay there slack, and become laughable. The art of manipulating the flow of information, while anticipating the way the mind receives that information, is not unlike the tricks and feats practiced by magicians, or mentalists, or even con-men. (Orson Welles described filmmaking along these lines, as a grand “fakery,” and Citizen Kane is famous for playing with perception to produce its startling “special effects.”) With Del Toro, use of this art points toward a perverse Pandora’s Box in your own mind, one that invites you further in; it has less to do with manufacturing jump-out-of-your-seat scares or white-knuckle anticipatory preludes. His interest lies in bringing an overall design and look to a film, imbuing an unusual object or phenomenon with a gravity that tugs on the viewer’s curiosity. The spin-doctoring is in the details. At the beginning of the story, we see cockroaches clambering out of the stature in which the Cronos Device is hidden; later, we find out that the device itself once contained a living insect, which served as a “filter” through which its supernatural powers were exerted (And indeed, later, we see a larva of some sort is growing in its confines.) Such hints, never completely explained, taunt logic; yet never demolish it to the extent that it disappears completely, lest its absence prevent the director from substituting his own brand of logic into the proceedings, just when you aren’t looking.

Del Toro attempts this kind of tease, this artistic chicanery, throughout Cronos, but it is seldom as effective as in the scenes involving the device itself. Much of the narrative lumbers—always leaning forward, but perhaps in too understated a manner for its own good. It has the dignified, if limpid, aura of a famous poem or play translated awkwardly to the screen. However, Cronos is an original piece written by Del Toro; I suspect the reason for this stifled feeling is that he has simply not grown into his full expressive abilities yet. It required several more films before he brought to the cinema a mastery of magic realism worthy of his literary forbears in South America. But there is no mistaking its early mark on Cronos. For instance, in the climax of the story, after he has “died,” but before he rests in peace, Jesus’s skin starts to peel off in disturbingly large segments; it oozes a sticky film, and as Jesus pulls at the skin on his stomach, he reveals something beneath that looks white and bulbous. Perhaps it is the belly of an insect in a larval stage (?!). Is Jesus in danger of becoming a creature modeled on the Cronos Device’s insectile inhabitant? What is happening? We never find out: for now, the jack goes back in the box.

Information from VHS Sleeve

Year

1992

Run Time

92 minutes

Director

Guillermo del Torro

VHS Distributor

Vidmark Entertainment

Relevant Cast

Ron Perlman

Relevant Crew

[none]

Tag Line

[none]

Rating

R

Clamshell?

No

Quote

“Great Macabre Gusto… Exotic… Very Stylish and Sophisticated.”—The New York Times

Masterpiece?

No

More 31 Days of Horror V

-

The Dead Don’t Die

1975 -

The Brides Wore Blood

1972 -

Alligator

1980 -

Girl in Room 2A

1973 -

Zombie High

1987 -

Deathdream

1974 -

Link

1986 -

The Witching

1972 -

Nude for Satan

1974 -

Rock ‘n’ Roll Nightmare

1987 -

The Strangeness

1985 -

Brides of the Beast

1968 -

Seven Deaths in the Cat’s Eye

1973 -

The Curse of Bigfoot

1976 -

Dark Night of the Scarecrow

1981 -

Chopping Mall

1986 -

The Jar

1984 -

Killer Workout

1986 -

Moon in Scorpio

1987 -

The Legend of Hell House

1973 -

Cronos

1993 -

Black Christmas

1974 -

Grave of the Vampire

1974 -

Rana: The Legend of Shadow Lake

1975 -

Blood Voyage

1976 -

Fiend

1981 -

Anguish

1987 -

The Chilling

1989 -

Attack of the Beast Creatures

1985 -

Humanoids from the Deep

1980

We don’t do comments anymore, but you may contact us here or find us on Twitter or Facebook.