Reviews

Gary Graver

USA, 1987

Credits

Review by Adam Balz

Posted on 19 October 2008

Source Trans World Entertainment VHS

Categories 31 Days of Horror V

“I mean nobody – nobody – goes off on their honeymoon with war buddies.”

The box covers of horror films are notoriously deceptive. They lie for attention—to be picked up off video-store shelves, looked at, absorbed with interest, and purchased. The disappointment that follows is unimportant, at least to the stores and studios: You’ve already bought it, probably for cheap, and probably used, so there’s no chance of it being brought back for a refund; worst case scenario, it’s either thrown away or sold for even less at a garage sale or thrift store, forever caught in a cycle of lies begetting letdowns. For viewers, though, the disappointment is twofold: Not only have we been duped into buying something we didn’t want or wouldn’t expect, but the movie we did look forward to seeing doesn’t exist, and probably never will.

Gary Graver’s Moon in Scorpio is no exception. The videocassette box has a fascinating front cover: An artistic rendering of a yacht with torn sails motionless in the open sea; to its back are clouds assembled in the shape of a skull, and floating in the waves is the silhouette of a scorpion. And, best of all, the sailboat and title are raised—an overused innovation in commerciality that makes anything written by Stephen King or R.L. Stine so fascinating to have and hold. Run your fingers across the dimensional cardboard and you’re immediately intrigued.

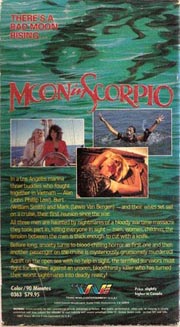

The back cover, on the other hand, is a canvass of irregularities and outright deceit. The price in the bottom-left corner is $79.95—an amusing number if accurate, considering I bought the tape online for little more than a buck. (According to the bottom-right corner, this price is “slightly higher in Canada.”) The write-up of the film’s plot, those ever-tantalizing and often vague paragraphs of hints and nudges and misused exclamation points, assures us this is the story of “three buddies who fought together in Vietnam…and their wives” stranded at sea with a killer; there is even a still photograph of one of the women sprawled across the deck, throat slit and blood pooling messily around her.

One of the other stills in the center of the back cover is of a Vietnamese man – his face pickled and rotten, his arms outstretched – rising from the sea. Taken with the short paragraphs about the film’s plot, this image seems to feed perfectly the idea that, once the tape slips into our VCR and the film begins, we’ll be offered ninety minutes of zombie-led bloodshed—a tale of at-sea revenge. And yet, as the closing credits roll, we’re abandoned—this decomposing man, as well as the horde of other undead innocents we’ve imagined, is never seen. There are no zombies, no great army of slaughtered men and women and children rising from the waters for the sake of retribution, no spine-tingling showdown between past and present. Instead we have a dull, borderline hokey story of a sailing vacation gone awry, one populated by terrible acting, bad sets, lazy cinematography, ridiculous dialogue, and an unimaginative story.

For instance, the six passengers are barely a mile or two from the shore. In more than one scene, as the characters begin to fall apart under the threat of death, their expressions revealing a panic over being “adrift at sea” (according to the back cover), with no key to the engine and all communication cut, Pacific-coast mountains are visible in the distance, and we’re forced to wonder why they don’t swim away from the boat or shoot a flare or even just call across the water for help. Or, for that matter, why no one on shore has noticed this yacht, its sails down, inactive for days, and called the Coast Guard. When the killer strikes, it happens with a certain level of farce: Three of the characters, almost in assembly-line fashion, are standing on the deck when the killer stabs them with a kitchen knife and slits their throats using what appears to be a modified harpoon—a glove-like contraption with extendable blades that, for whatever reason, goes completely unnoticed in one of the ship’s few cabinets earlier on.

Even before our characters set out to sea, the film doesn’t hesitate to demonstrate what a wreck it is. The Vietnam War, offered in flashbacks, is fought in what appears to be a Northern California forest mid-autumn, and the innocent Vietnamese our war buddies mow down are dressed in bright, spotless clothes directly from a Sears catalogue. This image is accompanied by another, of Allen stumbling in a shallow river and becoming entangled in a skeleton; and in what should be one of the film’s most horrifying moments – inoffensive Allen struggling with the body of someone more than likely killed by American soldiers – we are instead reminded of the scene in Ed Wood when Bela Lugosi, as portrayed by Martin Landau, is forced to lie in a cold pond and flail the lifeless tentacles of a fake octopus.

And the flashbacks, oh the flashbacks! To diagram this film based on its supposedly coherent timeframe is to commit one’s self to understanding a helplessly convoluted chronology. We open with a shot of Linda, our heroine with the heavy dialect, muttering about the “moon in Scorpio,” and sitting in what appears to be an asylum, her arms held tightly against her chest and bars of light – from, we presume, a door or window – splayed across her body and across the wall. We are then transported back in time – or are we? – to our killer escaping the very same hospital. Dressed in black, this figure kills a doctor and nurse before entering the hospital’s parking structure, gutting a pharmaceutical salesman, and taking his car. By the very next scene the hospital administration has asked an eccentric and sexually lascivious police detective to track the killer down.

Within seconds – the very next scene – the detective boards the yacht and encounters Linda quivering with fear below deck. Approaching her, she lashes out and stabs him in the gut – with the killer’s weapon, we soon discover – and the moment cuts to her sitting in the office of Doctor Torrence, where she relates her story at his request, prompting the start of flashbacks within flashbacks, each one compounding the next until the entire film becomes a muddled, unimportant, snowballed collection of unreliable memories and memories-of-memories.

I said “Or are we?” about the killer’s introduction, not because there is a chance at first that Linda is the killer, though the plot’s numerous holes do leave this open as a possibility, but because, taken as something that happens only days before the buddies’ sailing trip, it makes little sense come the closing revelations—that the killer is the wife of Mark, one of the vets and a writer whose new novel, as it turns out, contains a chapter in which a sister-figure has her throat sit and is repeatedly raped. His wife is a seductress who introduces her fellow vacationers to the idea of the moon being “in Scorpio,” a concept she explains but no one seems to understand.

And yet this woman, who we discover is an escaped psychopathic killer, is also, according to both the box cover and the film itself, Mark’s loving wife. And so, not only did she escape from the hospital by killing three people, but she also managed to find Mark, marry him, make arrangements for the boat trip by talking to the other veterans’ wives, pack food for the trip, and create an entire relationship history in a matter of hours. Or we could argue that she and Mark have been married for years, that he knows she’s a homicidal maniac with a love of hybrid fishing weaponry, that he helped her escape the confines of the hospital by sneaking her a knife and a change of clothes, that he kept knowledge of her from all his friends – this is their first reunion since the war ended, we’re told – while staving off hurried questions from the police as to where she might be, now that she’s fled her room and left a trail of blood. Still, no matter who she is or how she is linked to Mark, her demeanor is too bizarre and outlandish, and we as the viewer suspect her immediately.

There is a certain nostalgic quality to deceptive box covers. With the advent of the Internet there is very little risk – or, if you like, opportunity – to be swindled by studios looking to make a quick buck with misleading plot summaries, foreign images, hypnotic artwork, a cast of recognizable A- or B-listers, or self-bloating praise from critics. If we don’t know what a film is about, or if we don’t trust what we see, we Google the movie, and in less than a second we are offered a buffet of reliable and semi-reliable thoughts—praises, criticisms, warnings—all about that specific work. It takes the gamble out of watching movies like these – bad movies, forgotten movies – but it also takes out much of the fun, especially when uptight viewers begin tossing around the phrase “truth in advertising.” Am I sore that Moon in Scorpio was paraded in front of me under a cloak of small fibs? I suppose I am, to a degree. But then again, as some have noted, sometimes the best part about a horror movie is the cardboard cover wrapped around the videocassette, and Moon in Scorpio is no exception.

More 31 Days of Horror V

-

The Dead Don’t Die

1975 -

The Brides Wore Blood

1972 -

Alligator

1980 -

Girl in Room 2A

1973 -

Zombie High

1987 -

Deathdream

1974 -

Link

1986 -

The Witching

1972 -

Nude for Satan

1974 -

Rock ‘n’ Roll Nightmare

1987 -

The Strangeness

1985 -

Brides of the Beast

1968 -

Seven Deaths in the Cat’s Eye

1973 -

The Curse of Bigfoot

1976 -

Dark Night of the Scarecrow

1981 -

Chopping Mall

1986 -

The Jar

1984 -

Killer Workout

1986 -

Moon in Scorpio

1987 -

The Legend of Hell House

1973 -

Cronos

1993 -

Black Christmas

1974 -

Grave of the Vampire

1974 -

Rana: The Legend of Shadow Lake

1975 -

Blood Voyage

1976 -

Fiend

1981 -

Anguish

1987 -

The Chilling

1989 -

Attack of the Beast Creatures

1985 -

Humanoids from the Deep

1980

We don’t do comments anymore, but you may contact us here or find us on Twitter or Facebook.