Reviews

Fritz Lang

Germany, 1919

Credits

Review by Jared Eisenstat

Posted on 06 March 2014

Source Kino DVD

Categories Silent Lang

On the eve of a great boat race across the Pacific, the elite of society gather in a swanky hotel in San Francisco for a lavish banquet. The guests are gussied up for the white-tie soiree, the men debonair in coattails and slicked back hair while the women exude elegance in soigné dresses and perfect coiffures. They sit at dining tables decked out in white linen, the fine china laden with delicacies and the crystal glasses heavy with wine of choice vintage. It’s a perfect picture of American blueblood social life circa 1920. All that’s missing from the image, and the single empty chair at the table, is the dashing hero of the thrilling adventure film about to unfold: the strapping, virile, well-bred Kay Hoog (Carl de Vogt). Hoog is a leisure-class sportsman, globetrotting explorer, and eligible bachelor of impeccable manner and visage. A pure fantasy ideal of masculinity.

When Hoog finally arrives at the hotel—where his cape and cane are swiftly whisked away by attendants—he sits down and casually thumbs through a newspaper, utterly at ease and in no rush to join the party upstairs. Instead, the party comes to him, as the guests descend the staircase, and Kay finally explains the cause of his delay to the rapt assembly of social aristocracy. While cruising around in his yacht earlier in the day, he found a floating bottle with a message inside. Sent by a desperate castaway, it tells the coordinates of an island off of Peru where a lost civilization survives, hidden from view. There, they guard treasures beyond imagination.

So begins—excepting a brief prologue, in which we see the haggard old castaway write the message and hurl the bottle into the sea—the first episode of the Fritz Lang silent German serial Die Spinnen (The Spiders). It was Lang’s third film, and is the oldest extant movie directed by the Vienna-born filmmaker. His previous two, Halbblut (Half-blood) and Der Herr der Liebe (The Master of Love), both from 1919, are lost to history, or perhaps moldering away in some forgotten corner of a neglected archive or attic.

The Spiders was intended as a four-part epic, along the model of the French serials by Feuillade, such as Fantômas and Judex, and the Pearl White weekly shorts such as The Perils of Pauline. From the launch of episode one in October 1919, the new series was a commercial success. Lang had been slated to direct The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, but had to abandon that project because the spectacular performance of The Golden Lake sped up the timeline for the next episode of The Spiders. The German press applauded the first film, with a critic in Der Kinematograph gushing over “the sensational effects which strain the spectators’ nerves to their utmost.” The effects might have lost some of their potency over the years, but they are still a pleasure to watch. The critics also heralded the film as a sign of the nation’s resurgent film industry, and its readiness to take on the Hollywood-dominated world market. But Lang only got to finish the first two parts of the series before abandoning the project. He chafed at his treatment by the film studio Decla, under Weimar producer nonpareil Erich Pommer, severing ties there and leaving the final two episodes forever unrealized. Lang was both director and sole author of the two parts of The Spiders that were completed, Der Goldene See (The Golden Lake) from 1919 and Das Brillantenschiff (The Diamond Ship) from 1920, making the series an especially valuable resource for gleaning insight into his early film aesthetic and thematic obsessions.

What do we find in this nearly three-hour, halfway-realized series? It’s a mad dash of good and evil across the globe, and a succession of thrills and attractions spiced with backroom scheming and chicanery. In Lang’s vision, the mystique of the ancient world blends with the bustling novelties of modern times. He plays with the line between science and the occult, the natural world and rational society, history and fantasy. Inca warriors collide with high-tech gadgetry and pagan rituals brush up against the rites of urban life. Through it all, a lone virtuous man of action vies single-handedly against an intercontinental cabal of unsavory criminals calling itself The Spiders. Led in part by the devious femme fatale Lio Sha (Ressel Orla), Hoog’s nemesis, its ranks are filled with rapacious capitalists and ethnic others, all caricatured with evident delight by Lang.

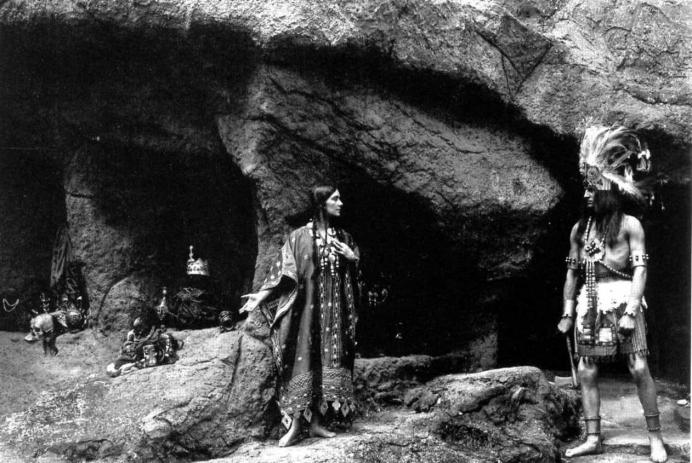

In the brisk, 69-minute The Golden Lake, Kay Hoog sets off on a journey to a mysterious Inca island in a race against Lio Sha and her Spider henchmen. Once he arrives there, he comes across the beautiful Naela (Lil Dagover), a native priestess brimming with innocence and purity of heart. Dagover, alluring even in her ankle-length poncho, is the most nimble actor here, as she glides across the caves and makes subtle, graceful gestures. She is perhaps the most expressive as well, though sometimes this finds her in the theatrical pose of shifting her body and eyes toward the camera for emphasis. As the Inca begin their bloody rituals, and The Spiders descend upon the Inca caves, Hoog must defeat both enemy factions while also saving some among them.

Police raids and underground cities, pirate treasure and a cave with poison gas, and a hypnotist yogi and a four-fingered man: these are just a small sampling of what the second episode of The Spiders bundles together. The Diamond Ship begins in a major US city, and we are swiftly plunged into the midst of a robbery. Much of the scene unfolds in a stylized long take, with a high angle shot of masked thieves in top hats and derbies prowling about a room as a security guard makes the rounds. The elevated view allows viewer’s to see past the grid of partition walls and into each office. A tense yet comic scene ensues as the burglars rush from office to office to evade detection. Finally, they jump the guard, break into the safe, and make off with the loot. We soon learn that the heist was all part of The Spiders’ latest scheme. They seek a powerful diamond in the shape of a Buddha, reputed to grant the power to wrest control of Asia away from foreigners and give dominion to whoever holds the stone.

Carl de Vogt and Ressel Orla return in part two to reprise their leading roles as Kay Hoog and Lio Sha. De Vogt has the physique, good looks and imposing presence needed for the role of Kay Hoog. He spends nearly the entire series, though, within the narrow emotional spectrum ranging from “Very Serious” to “A Little Happy, But Still Pretty Serious.” There are few of the little gestures and signs of a lively interior that could make Hoog the more persuasive, appealing character that Lang seems to intend for the role. Yet, de Vogt does have fine moments, as when he acts sly while incognito, or betrays in a flash across the face an almost cruel pleasure when he bests an opponent. For her part, Orla imbues Lio Sha with a palpable petty malice, and exudes the sense that a host of long-forgotten slights and distant traumas motivate her depravity. Still, there’s a plainness and lack of imagination to her movements and gestures. Orla’s Lio Sha lacks sensuality and charisma even in the scene when she tries to seduce Hoog. After these films, neither de Vogt nor Orla would ever assume a leading role in such a major movie. Kay Hoog and Lio Sha remain the parts for which they are best known.

The Golden Lake is the shorter of the two episodes, and it is both more compact and conventional. In heftier 104-minute The Diamond Ship, the story gets more tangled. It may at times lose its hold of the viewer, but it is a more ambitious film. Plot twists accrue, characters multiply, and Lang omits details to inject some ambiguity where before there was clear logical progression between scenes. He also grafts more social commentary onto what had been a bare-bones adventure story in episode one, further emphasizing issues of geopolitics and the rampant greed of society. There is also more formal experimentation, as with the bolder use of split screens, off-angle shots, shadows, complex cross-cutting, and superimpositions and fades. These changes are due in part to Karl Freund, who was the primary cinematographer on the second episode. Freund was an innovator in lighting, camera tech and shooting, and would go on to photograph Lang’s Metropolis and Browning’s Dracula.

These films are chock full of adventure-story cliché and spectacle, with Lang out to best Hollywood by cramming in sensational scenes and plot details. Exotic locales, ethnic caricature, human sacrifice and death-defying escapes abound. We travel over land, sea and air, and Hoog gets to parachute out in both episodes. Gunfights, swordplay, high-speed chases, and good old-fashioned pugilism enliven the action. It is a vision of a mostly bygone era, a mythologized age of adventure where setting foot in the unknown was a prelude to conquest and colonization.

But spare of literary high-art pretension, The Spiders is intent on entertaining with a rip-roaring yarn filled with action and intrigue rather than encoding deep messages about life. The effect of it all is rather similar to the Indiana Jones series. Where Spielberg and Lucas pay homage to action-packed 1950s B-serials of their childhood, The Spiders is in part a tribute to the stories and imagery of Lang’s youth: the titillating penny dreadfuls and serials by the likes of Jules Verne, Charles Dickens, Arthur Conan Doyle and German author Karl May. May wrote wildly popular Westerns, and helped launch a craze for “cowboys and Indians” in Germany that lasts to this day. Sensationalized tales in the popular press about real-life explorers and adventurers, enriched with photographs, added further to the creative texture of Lang’s boyhood. Perhaps exemplary is the case of Hiram Bingham, whose exploits were celebrated around the world when Lang was a young man gadding about Europe. Bingham, a Yale professor and explorer, was hailed as the discoverer of the lost city of Machu Picchu, the ancient Inca capital. The first episode of The Spiders revolves around a lost Inca city, and Bingham and his story may be an inspiration. The Yale professor is also rumored to be an inspiration for the character of Indiana Jones.

While there are multiple versions of The Spiders available now, all of them derive primarily from a damaged print recovered in the 1970s. Prior to that, it was thought the series was completely lost. Although it was shot on black and white film, there is significant tinting, and the color can change dramatically between scenes and sometimes between the shots in a single scene. The Spiders is most widely available in the U.S. in a digitally remastered version released in 2012 by Kino Classics, with a light new musical score by silent film accompanist Ben Model. The Kino version includes some scenes that were apparently missing from early cuts of the restored film, along with some different tinting and frame rates.

The Spiders were made just after the Great War, in a devastated Germany traumatized by its loss and beset by internecine fighting between radical and reactionary forces over the future shape of the nation. The Sparticist uprising exploded in Lang’s adopted city of Berlin in early 1919, until it’s bloody end several months before filming of The Spiders began. Lang was likely working on the script for the serial around this time, or shortly afterward. Amidst this divisive tumult, it is perhaps unsurprising that Lang chose to set the series outside of real-world events, and even outside of Germany and continental Europe. Still, there is a pervasive sense of dread in these films, of nefarious elements that threaten society and a vast underworld that is veiled by the surface of things. Anybody, at any level of society, may be corrupt, or corruptible through greed. Therefore, nobody is to be trusted.

This is emphasized by Lang’s fixation on surveillance in the two films. Everybody seems to be watching and being watched in turn, and the camera angles and positions elevate the sense of rampant secret observation. At any moment we may be spied, and Lang shows us all the different places and ways this might happen. Optical devices such as magnifying glasses and telescopes abound, and there are even small screens that presage closed circuit monitors. Lang was an aspiring painter while living in Brussels and Paris in his twenties, and during the First World War distinguished himself on perilous scouting and reconnaissance missions in service to the Austro-Hungarian army. This endless looking and observation—even his chosen affectation of a monocle—hint at Lang’s obsession with ways of seeing, and being seen.

Sources:

Eisner, Lotte H. Fritz Lang. New York: Oxford University Press, 1977

Gunning, Tom. The films of Fritz Lang: allegories of vision and modernity. London. British Film Institute, 2000.

Koller, Michael. “Kitsche, Sensation — Kultur und Film: Die Spinnen.” Senses of Cinema. Cinématheque Annotations on Film, Issue 21. Accessible at: http://sensesofcinema.com/2002/cteq/spinnen/

Lang, Fritz, and Barry Keith Grant. Fritz Lang: Interviews. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2003.

McGilligan, Patrick. Fritz Lang: The nature of the beast. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1997.

More Silent Lang

-

Harakiri

1919 -

The Spiders

1919 -

The Wandering Shadow

1920 -

Destiny

1921 -

Four Around the Woman

1921 -

Dr. Mabuse the Gambler

1922 -

Die Nibelungen

1924 -

Metropolis

1927 -

Spies

1928 -

Woman in the Moon

1929

We don’t do comments anymore, but you may contact us here or find us on Twitter or Facebook.