Reviews

L.Q. Jones

USA, 1975

Credits

Review by Budd Wilkins

Posted on 07 August 2013

Source Sling Shot Entertainment DVD

Categories Favorites: The Apocalypse

A Boy and His Dog was written and directed by L.Q. Jones. Perhaps better known as an actor, a regular member of Sam Peckinpah’s repertory company, Jones adapts Harlan Ellison’s award-winning novella of the same name into a blackly humorous post-apocalyptic fable about loyalty and survival. A Boy and His Dog opens with a proverbial bang as mushroom clouds fill the frame. The opening crawl matter-of-factly informs us:

World War IV lasted five days. Politicians had finally solved the problem of urban blight.

America in 2024 is as harshly divided as the diametrically opposed landscapes against which the film’s action takes place—the barren aridity of life aboveground and the ersatz fecundity in the “downunder” called Topeka whose citizens cling desperately to outmoded forms of collective existence. These contrasting topographies aren’t only physical landscapes; each one also tweaks a different aspect of sanctimonious American doublespeak.

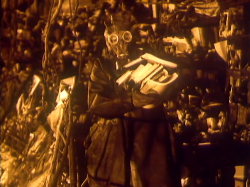

Aboveground represents the worst case scenario for the frontier ideal of rugged individualism, a vision of life in the desert of the real, with isolated “solos” wandering the mud-packed plains, fighting off packs of marauding rovers, foraging for whatever supplies they can find, and ravaging any unprotected females they happen across. A solo like our hero Vic is a dying breed, assisted in his daily struggle for survival by a hyper-intelligent dog called Blood with whom he has a special telepathic link. In this brave new world, women are little more than commodities prized for their scarcity, but never esteemed above their use value. When Vic and Blood run across the remains of a woman who’s been mangled and manhandled by a pack, Vic grumbles: “They didn’t have to cut her! She could have been used two or three more times!”

Even in a society where life is this nasty, brutish, and short, mass entertainment isn’t entirely dead, although post-apocalyptic popular culture seems to have devolved to the point that it’s little more than softcore pornography and shoot-‘em-ups with titles like A Fistful of Rawhide. (In a deprecating self-reflexive jab, some of the battered footage on the screen was culled from Jones’s directorial debut The Devil’s Bedroom.) Then again, maybe the scene is more of a commentary on contemporary film culture. On the DVD commentary track, Jones remarks how easy it would have been to play up the T&A factor and the violence, before pointing out that George Miller’s Mad Max approached comparable material “from the commercial angle.” True enough, Jones’ film doesn’t go out of its way to win over viewers with an ensemble cast of uniformly unlikeable characters. About this, Jones jokes, “The dog’s the only human in the picture!”

The flipside of the aboveground “war of all against all,” Topeka instead offers the surreal spectacle of small town America petrified in amber. Viewers are treated to a visual compendium of Americana: marching bands, picnic tables heaped with corn and apple pies, the soothing sounds of a cappella quartets, all the appurtenances of bland Middle American contentment. Only the citizenry have their faces plastered with pancake make-up. It’s as though George Romero had brought to undead animation one of Norman Rockwell’s iconic images. Adding to the uncanny quality of these festivities is the fact that they take place under cover of perpetual night. Indeed, all the scenes set in Topeka are rendered eerily claustrophobic by the simple means of swathing them in shadows.

Topeka is ruled by the Committee, an oligarchy in Pollyanna attire whose homespun proclamations are broadcast nonstop via loudspeakers positioned everywhere around the town. As with some of the best socially-minded melodramas of the 1950s like Bigger Than Life and All That Heaven Allows, the presentation of this society keys into the conformist underbelly of an often idolized (and idealized) decade. Any deviation from the Committee’s blinkered vision of normalcy is met with condign punishment. “Lack of respect, wrong attitude, failure to obey authority” is the Committee’s unwavering verdict when sentencing malcontents, handed down with all the casual indifference of a fait accompli. Offenders are promptly “put out to farm,” which is the Committee’s nifty little euphemism for summary execution.

Far from being the barbarian at the gates, Vic has been lured underground by a girl called Quilla June at the behest of the Committee because, despite the apparent aura of affluence, Topeka’s citizenry lacks one key resource: Dwelling underground has rendered the men infertile. Initially overjoyed at the prospect of servicing the womenfolk, Vic discovers that his raging libido will be subjected to the ruthless rationality of modern mechanization. He’s hooked up to an electro-ejaculation machine and “married off” to a succession of young women, each of whom receives a test tube’s worth of his semen, in a grotesque travesty of holy matrimony. The minister nervously demurs “Can we please keep to the schedule?” as the doctor continues checking names off the list chalked up on a blackboard.

A Boy and His Dog has caught a lot of flak over the years for the questionable taste of its finale, as well as the perceived misogyny underlying its punning final line. Certainly such a reading remains available should you require it. But the point the filmmakers are trying to make is that this particular woman is false, not that all women necessarily are. Vic has to make a choice between mendacity and shamelessly shammed affection on the one hand, and real love and loyalty on the other. The fact that he chooses his dog shouldn’t leave a bad taste in anybody’s mouth.

More Favorites: The Apocalypse

-

The War Game

1965 -

On The Beach

1959 -

Where Have All the People Gone

1974 -

A Boy and His Dog

1975 -

Bug

1975 -

La Soufrière

1977 -

Escape from New York

1981 -

The Road Warrior

1981 -

Le Dernier Combat

1983 -

Night of the Comet

1984 -

Threads

1984 -

The Terminator

1984 -

Def-Con 4

1984 -

Letters From a Dead Man

1986 -

Miracle Mile

1988 -

Last Night

1988 -

Last Days

2005 -

The Rapture

1991 -

Southland Tales

2006 -

Idiocracy

2006 -

The Happening

2008 -

The Road

2009 -

Cosmopolis

2012

We don’t do comments anymore, but you may contact us here or find us on Twitter or Facebook.