Reviews

The Last Battle

Luc Besson

France, 1983

Credits

Review by Steve Macfarlane

Posted on 13 August 2013

Source Sony Pictures DVD

Categories Favorites: The Apocalypse

It jostles the mind to realize that Luc Besson was 23 when he wrote and directed Le Dernier Combat. While the film’s heart is syrupy-sentimental (who’s shocked?), its surfaces are clean, incremental, reverently silent—appropriate, given that the film takes place in a desert wasteland where there are about ten times as many men as there are women, and humankind has lost its ability to speak. Besson never attempts to explain what happened on either score, and that’s to the film’s credit—like the epic magic realism of Children of Men, Le Dernier Combat sees an elegantly simple apocalypse concept strung out to its fullest implications for a handful of characters, less concerned with some specious exposition-dump than the gritty contours of its fallout. (For the exact opposite approach to these tectonic crises, consult the first 40 minutes of pretty much any tentpole release this past summer.)

None of Besson’s hardscrabble road warriors have any dialogue, nor names. Whatever shit-talk the filmmaker has wracked up over the last three decades for adulterating traditional French cinema with U.S.-leaning bombast like Subway and Nikita (to say nothing of his own dalliances with Hollywood proper), this film is constructed more in the lineage of Jacques Tati or Sergio Leone. The opening shot is a pip: the camera pans around an empty, dessicated floor of a high-rise office building with wind rustling its slackened blinds. Evidence of human life is strewn everywhere, a man (Pierre Jolivet, Besson’s cowriter) is moaning softly in the background. As the camera tracks up to Jolivet’s feet sticking out under a bed the implication of sex is clear, but just as Besson’s frame crests up and hits Jolivet’s shoulders we realize he is having sex with an inflatable mannequin, and by the time this fact has sunk in, the balloon is popped—she wheezes herself down to nothing and Jolivet returns to the real world. Crude stuff, maybe, and a little too perfect in its technique, but the first of many instances that see Besson’s filmmaking swinging for the fences.

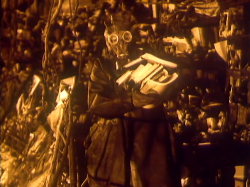

The next scene witnesses a homunculoid steampunk being shoved into a deep, dark desert mine, extracting tiny vials of an indeterminate liquid - alcohol? oil? - for a swarm of hideously haggard men in tattered suits, living in their cars. Besson’s vision of a piecemeal post-apocalyptic sub-micro-economy makes for a veritable daisy-chain between the men, absurd when viewed at large (i.e. through Jolivet’s binoculars) but fraught and hyperreal in its intimacy. And these long passages, like riffs on the mundane details we all take for granted in our pre-apocalyptic day-to-day lives, are ultimately Le Dernier Combat’s left hook. Any schmuck in Hollywood with a laptop can envision a pretty good doomsday, but Besson is solely concerned with rendering a shellshocked, tone-deaf aftermath. Besson creates a world - here strewn with the leftovers of unexplained, disappeared millions - that gets proportionately more dangerous as the space between people is extended.

Jolivet manages to break into a walled-in pseudo-hospital where a doctor reveals an anesthetic-modified treatment that could, potentially, restore both men’s voices. And better still: a beautiful young woman, locked in maximum security, carefully fed and otherwise ignored by the doctor—cultivated, as it were, for mankind’s big comeback. Jolivet’s melancholy fixation on her spindly feminine hands reaching through her prison to receive lunch is but one of many of Besson’s mixed ethical signals. The “last battle” promised by the title is of course an inversion, a final duel between Jolivet and his semi-rival Jean Reno (credited as playing “The Brute”). Again, Besson draws an absurd miniature with huge political implications - two men fighting over a woman whom neither has ever fully seen. The skirmish sees them carelessly destroying most of the manicured interior world of doctor’s hospital, colliding through bookshelves, lawn furniture, pots and pans, detritus. The worst critique one could make is that Besson’s freakish attenuation to minutiae is more rewarding for tone than story, but what apocalypse scenario hadn’t been burnt to the ground already by 1983?

Postscript: Besson’s 11-minute prototype for this film, L’avant Dernier, is available on YouTube in full and highly recommended. The short version also stars Jean Reno and Pierre Jolivet, and is simultaneously bleaker and less fixed in its dramatic mode, thanks in part to Eric Serra’s smooth jazz soundtrack. Indeed, by having Jolivet listen to Serra’s music on cassette tapes in Le Dernier Combat, Besson handily collapsed the easy narratives of pre-apocalyptic life into nostalgia and regret, giving added oomph to Serra’s sometimes inappropriate squealing horns and synth-bass.

More Favorites: The Apocalypse

-

The War Game

1965 -

On The Beach

1959 -

Where Have All the People Gone

1974 -

A Boy and His Dog

1975 -

Bug

1975 -

La Soufrière

1977 -

Escape from New York

1981 -

The Road Warrior

1981 -

Le Dernier Combat

1983 -

Night of the Comet

1984 -

Threads

1984 -

The Terminator

1984 -

Def-Con 4

1984 -

Letters From a Dead Man

1986 -

Miracle Mile

1988 -

Last Night

1988 -

Last Days

2005 -

The Rapture

1991 -

Southland Tales

2006 -

Idiocracy

2006 -

The Happening

2008 -

The Road

2009 -

Cosmopolis

2012

We don’t do comments anymore, but you may contact us here or find us on Twitter or Facebook.