Reviews

Mick Jackson

UK/Australia/USA, 1984

Credits

Review by David Carter

Posted on 15 August 2013

Source BBC TV DVD

Categories Favorites: The Apocalypse

Now, this madness of war is once more spreading through the world and our brave country must again prepare itself to survive against great odds.

The above quote is an excerpt from a speech prepared in March of 1983 for Queen Elizabeth II in the event of war between the countries of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and those of the Warsaw Pact. Recently made public under the stipulations of Britain’s “30-year-rule,” the speech is a solemn reminder of just how real the threat of international conflict was during the early eighties. Hostile rhetoric between the United States and the Soviet Union was at unprecedented levels and would, ironically, peak in the months following the preparation of the Queen’s speech. President Ronald Reagan famously referred to the USSR as “an evil empire” in a speech arguing against nuclear freeze talks between the two nations. On September 1, 1983, the Soviet Union shot down Korean Airlines Flight 007 as it flew over Soviet airspace. Georgia Congressman Lawrence McDonald was among the 269 killed, and the incident brought the Cold War to a level of tension not seen since the Cuban Missile Crisis.

Fear of a coming nuclear war rippled through society, and reflections of this inevitably made their way into pop culture in the form of apocalyptic art. Gone was the innocence-via-ignorance of the “duck-and-cover” days, as post-apocalyptic cinema accepted as given that nuclear war would completely destroy global civilization. As tensions increased in 1983 and 1984, post-apocalyptic cinema changed as well, moving away from the action and horror themed entries of the late seventies towards a more realistic - and more frightening - vision of the future. Focus shifted from life after the “big event” to the big event itself.

US television led the way towards a style of post-apocalyptic cinema that can be described as “reality-based”—a preferable and more apt term than docudrama. The trend began with the 1982 NBC miniseries World War III, a strongly pro-war pot-boiler in which a peace-making US President outsmarts the USSR and deploys a first strike1. NBC would again tackle nuclear war with their 1983 broadcast of Special Bulletin, from which the 1984 HBO film Countdown to Looking Glass borrows its format. 1983 also saw the broadcasts of PBS’ Testament and ABC’s The Day After, an anti-war film that had a profound effect on US and Soviet policymakers, with Ronald Reagan in particular giving the film credit for changing his opinions on nuclear war. Each of these films was impactful in its own way, but it would be a 1984 BBC broadcast that emerged as the most realistic and truly terrifying of this cycle of films. Barry Hines and Mick Jackson’s Threads avoided the rampant nationalism of its American counterparts to give a precise, almost clinical, depiction of nuclear war and its effects.

On screen titles give the date and setting of the film prior to the introduction of any characters: Sheffield, England, Saturday, March 5. Young couple Jimmy and Ruth are the de facto main characters, and we are first introduced to them as they quarrel and then reconcile on a hill overlooking the city. We see Jimmy and Ruth’s relationship escalate quickly over the coming days via an unplanned pregnancy. This rapid escalation is mirrored by the escalating tensions between the US and USSR, who are locked in a standoff in Iran. Scenes of the couple starting their lives together are intercut with Britain’s war preparations. The Sheffield City Council are moved into a bunker to serve as a provisional local government should war occur, and the UK begins food rationing and the arrest of “known subversives.” All of Britain begins preparing for nuclear attack after a limited nuclear exchange occurs in Iran.

At 8:30AM local time on May 5, the Soviet Union detonates a warhead over the North Sea, hitting the United Kingdom with an 80 megaton blast and instantly killing between two and nine million people. The resulting pulse destroys all electronics, rendering all vehicles and communications equipment useless. Jimmy and Ruth search for one another amidst the chaos, but moments later the USSR begins striking key NATO installations, including Sheffield. By the day’s end, approximately 30 million people in the United Kingdom - over half the population - have been killed.

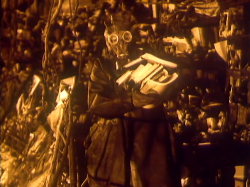

Ruth survives the attacks and is faced with the grim task of living in the post-apocalyptic world. Nuclear winter blankets the atmosphere with ash, causing perpetual darkness and freezing temperatures. The narrative style of the pre-apocalyptic section gives way to a more traditional documentary style, and voice-over narration provides the context for the horrific scenes of the short lives of the survivors. The leaps between time periods becomes greater; days turn to weeks then to months until we are finally given a look at Ruth and her child ten years after the nuclear war. Rather than giving hope for the future, Threads ends on a chilling note that implies the first decade was only the beginning of the horrors.

Threads is based on the real contingency plans Britain had in place for war and scientific modeling of life after full nuclear war. The use of real projections coupled with the UK setting allowed Threads to avoid the politics present in other reality-based nuclear war films. The scenario in the film in one in which the UK is a third party to the conflict, not a direct participant, removing the aggressor/victim dynamic that would be present had it been set in the US or USSR and allowing the suddenness of the escalation to be more readily shown. Therefore Threads breaks from its American counterparts by never entertaining the then politically popular idea of a “winnable” nuclear war. The film is quite clear on the point that ideas like first strike capabilities and retaliatory strategies are meaningless: once nuclear war breaks out, all parties involved will be destroyed. Threads makes this point bluntly and repeatedly, doing so in a manner that makes it inarguable.

Threads avoids politics at the nation-state level, but I would argue that it is very concerned with politics at an individual level. While Jimmy, Ruth, and their families are fretting and arguing over their predicament, the US/Soviet conflict is literally background noise. The audience only hears snippets of it on radio and TV broadcasts, or as headlines in news shops. As stand-ins for all Britons and, to a degree, all people, Threads conspicuously makes the point that they do not care about the conflict until it directly affects their lives. An anti-nuclear demonstration is shown in the days before the war, but it is framed as a futile gesture, one done too late to make a difference. The second half of Threads is a strong argument against nuclear war, but I believe the first half to be an equally compelling argument against leaving that decision solely up to the politicians. While it doesn’t belabor the point, Threads’ anti-apathy message is as powerful as its anti-nuclear one.

If the film has a flaw it is in its focus on the young couple and, later, on Ruth alone. It is an attempt to make the unimaginable horror of nuclear war more relatable by tying it to the fate of a single individual, but it often has the opposite effect, diminishing the scope of the event through its focus on Ruth. As mentioned above, Jimmy and Ruth are oblivious to the coming war, a fact that paints them in an increasingly negative light in the minds’ of the audience as the film progresses. One imagines the film would have been more poignant had both perished in the war. I will, however, admit that Ruth’s survival allows a narratively expedient way to explore the differences in pre- and post-apocalyptic life. The scenes with Ruth’s child are less well-realized and the lack of narration or titles may cause some viewers to be confused as to what is occurring. The ideas conveyed by the film’s ending are clear, but the freeze-frame zoom and scream combination is quoted from innumerable slasher films and thus appears to be a cheap, exploitative ending to an otherwise somber work.

Threads is perhaps the strongest anti-nuclear film ever made, the closest thing available to a documentary on post-apocalyptic life. The film takes its title from the concept that all life on earth is interconnected as if by invisible “threads.” The ultimate message of the film is that nuclear war is not simply an issue for politicians to debate, or for just the major nuclear powers. The threat of nuclear war affects all individuals equally and, as such, each individual is responsible for doing something about it. Even in the post-Cold War world of today, it is difficult to imagine anyone viewing Threads and not walking away from the film with that massive burden in the forefront of their minds.

- Peter Watkins’ 1965 The War Game is of course the first reality-based nuclear war film developed for television. However, since it was pulled from broadcast and shown in theatres, it is not part of this cycle. It would eventually be broadcast in 1985, after the shows discussed here had aired.

More Favorites: The Apocalypse

-

The War Game

1965 -

On The Beach

1959 -

Where Have All the People Gone

1974 -

A Boy and His Dog

1975 -

Bug

1975 -

La Soufrière

1977 -

Escape from New York

1981 -

The Road Warrior

1981 -

Le Dernier Combat

1983 -

Night of the Comet

1984 -

Threads

1984 -

The Terminator

1984 -

Def-Con 4

1984 -

Letters From a Dead Man

1986 -

Miracle Mile

1988 -

Last Night

1988 -

Last Days

2005 -

The Rapture

1991 -

Southland Tales

2006 -

Idiocracy

2006 -

The Happening

2008 -

The Road

2009 -

Cosmopolis

2012

We don’t do comments anymore, but you may contact us here or find us on Twitter or Facebook.