Reviews

John Landis

USA, 1981

Credits

Review by Victoria Large

Posted on 11 May 2012

Source Universal DVD

Categories Favorites: Transformations

An American Werewolf in London is one of those movies that I’ll never really be through with: there’s always going to be a next time, and I will never fail to sit watching it on cable even though I have it on DVD. It’s found its way under my skin.

Part of the film’s appeal is the fact that so many aspects of it sound infelicitous – indeed, willfully so – on paper, yet manage to work onscreen. Writer-director John Landis famously mixes seemingly clashing tones throughout. Dry, humorous dialogue and downright silly comedy (like a police inspector fumbling with a set of nesting bedpans or the lead actor racing around naked with only some stolen balloons to cover his most delicate parts) commingle with fearsome suspense sequences, throat-tearing gore, and well-chosen snatches of pathos. This is why Roger Ebert argued that “the laughs and the blood coexist very uneasily in this film†back in 1981 (it wasn’t a compliment), but it’s also the source of American Werewolf’s cult cool.

Indeed, like its eponymous monster, the film itself a shapeshifter, genial in one instant and vicious in the next. It begins with a likable pair of American tourists joking around as they travel through northern England and then brutally switches gears when the two young men are attacked on the moors under a full moon. One of them, Jack, is killed. The other, David, survives but is severely wounded and – no big spoiler, this – fated to transform into a wolf.

American Werewolf contains one of cinema’s most famous creature transformations, a tour-de-force of special effects that won Rick Baker the first competitive Academy Award for achievement in makeup. It starts with David leaping up from reading a book after an extended sequence of pacing and worrying in anticipation of the full moon. Shouting, “Jesus Christ! Jesus Christ! What?†before tearing at his clothing, he sweats and cries out in pain, then looks on in horror as his limbs begin to stretch, twist, and sprout hair. David writhes on the floor and we hear what sounds like cracking bone. It’s a far cry from the fade-in transformation of Lon Chaney Jr. in 1941’s The Wolfman (a film that gets name-checked and referenced throughout American Werewolf). This transformation looks like it hurts. It’s also held up quite well in the more than thirty years since the film’s release, though I should confess an eighties child’s bias in favor of practical effects over too-slick CGI.

Yet while the transformation scene is remarkable as a grisly technical watershed, it is also, and perhaps more importantly, a pitch-perfect centerpiece for American Werewolf’s brazen genre-bending style. The diegetic sound of the transformation scene is all creaks and cries and groans, but Landis’ twisted sense of humor comes out in the pop tune on the soundtrack: Sam Cooke’s gentle take on “Blue Moon.†Funnier and loopier still, Landis briefly cuts away from David’s agonizing change in favor of a close-up of a little Mickey Mouse doll standing on a table. And in the moment that comes close to summing it all up – funny and freaky and heartbreaking all at once – David calls for his dead friend Jack while in the throes of a transformation, apologizing for an earlier insult.

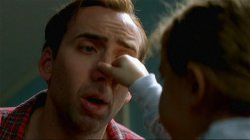

This may be the right time to mention that David’s transformation is not the only one in the film, and, if I’m honest, it’s not even the one that I find the most interesting. Jack reappears after his gruesome death, and he’s transformed, too—into a decaying corpse. He shows up in David’s hospital room with a clawed face and a glistening, shredded throat, still the cheerful, faithful friend that we met at the beginning of the film. It’s just that now he’s the undead harbinger of bad news, warning David to kill himself before the next full moon.

Jack’s transformation works so well – is so tragicomic and haunting and memorable – in large part because of Griffin Dunne’s performance. The actor (who has often mentioned how depressed he became on set while watching himself decompose) plays the dead Jack as joshing and upbeat, delivering a performance made up of tiny moments that are somehow sweet and horrible at once. We see Jack taking toast from David’s breakfast tray with a bloody hand and casually dunking it in an egg yolk or pausing to smell a flower before once again exhorting his friend to commit suicide. Jack’s transformation is in some ways an extended sight gag, but it also gets literally and figuratively closer to the bone than David’s change into a wolf. Jack’s not a mythical creature. He’s just dead. Perhaps it’s telling that the idea of a friend returning from the grave was actually what sparked Landis to write the screenplay in the first place.

Jack may remind us of our mortality, but David embodies our anxieties about what we might be or become. At the heart of his story is guilt. It isn’t just that David is unable to save Jack from the wolf at the beginning of the film; it’s that he doesn’t really try. In the scene on the moors, Jack pauses to help David up after the latter has slipped and fallen – that’s when he’s attacked – but once Jack is pinned down by the monster, David immediately runs from the scene, not turning back until it’s too late. It may be tough for the audience to blame him (self-preservation instincts are going to kick in when a werewolf attacks), but it’s easy to see why he might blame himself for his friend’s death.

Viewed in this light, it makes pointed thematic sense that David, played with boyish amiability by fresh-faced former Dr. Pepper pitchman David Naughton, spends so much time in the film worrying that he is a monster. He frequently examines himself in the mirror – before the transformation sequence, for instance – and his nightmares are mostly about being an aggressor rather than a victim. (A notable exception is the dream in which David’s family is attacked by demons that look like Nazi stormtroopers, one of a few places where the film rather explicitly speaks to, or perhaps from, the collective psychic scars of the twentieth century. In another instance, Jonathan Woodvine’s Dr. Hirsch, who has been established as a WWII veteran, cryptically tells David, “You’d be surprised what horrors a man is capable of.â€)

The guilt and anxiety doesn’t dissipate; it just builds to a crescendo, consistently undermining the film’s romantic subplot. After David has gone home with his sympathetic hospital nurse, Alex, and enjoyed a Van Morrison-soundtracked romp with her in the bedroom (and shower), he wakes in the middle of the night and finds his dead friend lurking in the bathroom mirror—a great stinger of a scare that’s been imitated ever since). Of course Jack is there. In the wake of the attack, David can’t simply be a young man enjoying a surprise love affair in London, not without consequence. (It’s worth noting that, in contrast to other horror films, sex is not the source of disaster here. The boy was doomed before he met the girl. He can’t escape the tragedy that he survived.)

David and Alex’s relationship is always slightly off—“I find you very attractive, and a little bit sad,†she tells him, seemingly drawn to David’s damaged qualities. Scenes of Jenny Agutter’s affectionate and protective Alex simultaneously mothering and flirting with the young American in her care (“Shall I be forced to feed you, David?â€) take the relationship into vaguely uncomfortable territory early in the game, but it’s the film’s shatteringly unsentimental conclusion, complete with harshly insensitive end title music (“Blue Moon,†again, this time The Marcels’ raucous doo-wop take) that really slaps us for even imagining that love could be the answer. It doesn’t even bother to apologize, either; it just ends and leaves us to cope.

All of which is pretty heavy for a film from the director who had thus far been best known for Animal House and The Blue Brothers, a film that, furthermore, contains such sprightly, quotable lines as “A naked American man stole my balloons!†And that’s kind of the point. American Werewolf is the spiritual godfather of comic horror films like Edgar Wright’s Shaun of the Dead, funny genre pieces that don’t pull their punches. Yet as influential as Landis’ film has become, it still feels bold and deeply, wonderfully strange. It remains one of cinema’s ultimate misfit toys, and I love it to death.

More Favorites: Transformations

-

Altered States

1980 -

Alien: Resurrection

1997 -

In the Mouth of Madness

1994 -

Now, Voyager

1942 -

Honey, I Shrunk the Kids

1989 -

The Toxic Avenger

1984 -

Teen Wolf

1985 -

Teen Wolf Too

1987 -

An American Werewolf in London

1981 -

The Curse of the Cat People

1944 -

Face/Off

1997 -

That Obscure Object of Desire

1977 -

Now, Voyager

1942 -

From Beyond

1986 -

The Beast Within

1982 -

The Family Man

2000 -

Starman

1984

We don’t do comments anymore, but you may contact us here or find us on Twitter or Facebook.