Reviews

Brett Ratner

USA, 2000

Credits

Review by Michael Nordine

Posted on 23 May 2012

Source Universal BRD

Categories Favorites: Transformations

This one included, I’ve now prefaced no fewer than three pieces with an admission of my affinity for Nicolas Cage. This speaks not only to the obvious fact that I have a soft spot for the actor, but also to his perception among discerning cinephiles and casual moviegoers alike: oddball, eccentric, batshit insane. Also that he’s in a lot of bad movies. None of these things are untrue, and yet for me part of Cage’s appeal lies in just how terrible so many of his projects end up being: the awfulness of The Wicker Man, Season of the Witch, and more than a few others in recent years ultimately serves to bring his singular talent into relief. No matter how ill-conceived the project, how fundamentally flawed the execution of a film’s every other element, here is an actor who never phones in a performance. His eccentricities - the Elvis obsession, the self-taught school of acting he calls Nouveau Shamanic, the massive debt - make a case for him not “selling out” with some of his choices but rather expressing a large, vital part of himself that none of us are likely to ever fully understand.

So to say I’m a Cage apologist wouldn’t be quite accurate, because I don’t think there’s anything to apologize for—he’s less a guilty pleasure and more a sometimes-misunderstood figure who deserves praise for always laying it all out on the line. Enter The Family Man, which ultimately lands closer to his best movies (Raising Arizona, Leaving Las Vegas, Adaptation.) than it does to his worst and is also one of his more subdued efforts. Not unlike one of its primary reference points, Frank Capra’s It’s a Wonderful Life (there’s even a bell motif), the film offers its protagonist a glimpse of what his life would have been like had he lived differently—or, in this case, reversed a single decision. There are other key differences as well: here, Cage’s Jack Campbell is wealthy in his “real” life but has no one to share it with; too, his glimpse accounts for the majority of the film’s runtime and isn’t an affirmation of the choices he’s made. Indeed, Jack’s eventual conflict is that, the more he sees of what could have been, the more he comes to appreciate it.

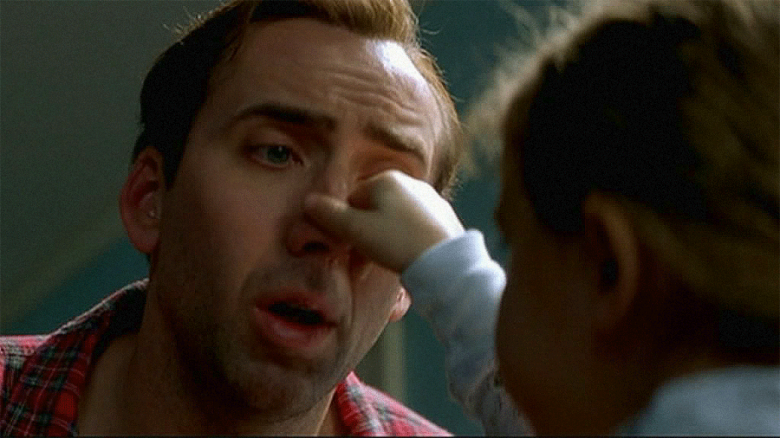

Bookended by airport scenes covering both ends of the fateful decision alluded to above, the film proper starts with an explication of Jack’s apparent dream life: waking up next to some fresh young thing in his penthouse apartment, driving to his corporate job in Manhattan, readying a multibillion-dollar merger. Jack sings opera as he dresses for work and embraces his lack of interpersonal attachments. “You’re a credit to capitalism,” his boss tells him as he works into the night on Christmas Eve and harangues others for their lack of enthusiasm in doing the same. Later that night, after ignoring a message from an old girlfriend named Kate and a chance encounter with a man we can only assume is an angel, he goes to sleep. Upon waking, he finds himself in the house he apparently shares with Kate and their children in New Jersey. This is the real world for everyone else, and the only odd detail is the look on Jack’s face at the moment he realizes where he is.

Seen through the lens of this transformation, The Family Man is something of an oddity. Jack is thrust into a life not at all his own but forced to keep up the act lest he appear insane; save for his precocious young daughter, no one has any sense of what’s happened to him and why he’s acting so strangely. Much of the film thus charts his gradual easing into this new role of father/husband/tire salesman and the many conflicting emotions that come with the territory—all of which is par for the course for a story of this sort. Where it manages to distinguish itself, then, is in the under- and overtones of melancholy coursing throughout every half-smile and downward glance. Like a kid at summer camp, Jack is pained at his arrival and and distraught upon his exit—for the first time in his life, he’s seen something he can’t have.

What the film most taps into, early and often, is the simple question of “What if?” It’s often on the nose (and certainly sentimental) in its handling of the many ways in which the simple act of getting on a plane irrevocably altered its hero’s life, but it’s also a heartfelt evocation of longing and regret. With neither of his two lives fully satisfying him, Jack spends much of the film battling - with himself, with his disappointments and shortcomings - and being reminded by Kate of things he already knows on a certain nonvocal level. A key scene finds him wanting to buy a $2,000 suit, her pointing out the ridiculousness of the idea, and him launching into a tirade: how he could have been so much more, how she should be as disappointed in their shared life as he is. Kate doesn’t see it that way. Her measure of success is vastly different from his, her countenance much more zen. It’s in the tension and interplay between the mostly happy couple that The Family Man finds its most rewarding material and, though certainly a bit rough around the edges, its emotional core makes it easy to appreciate as a classical (if not classic) entertainment. Brett Ratner is hardly nuanced as a director, ditto the film as a whole, but it nonetheless works well enough on a visceral level for none of that to matter much.

If I’m being honest, though, much of its appeal to me has always been its use of Chris Isaak’s “Wicked Game.” (Not coincidentally, this also accounts for part of my love for Wild at Heart.) The song plays over an early scene in which, their two kids asleep, Jack and Kate have a rare opportunity for intimacy. Suddenly feeling guilty for taking advantage of her emotions, Jack pretends to nod off. It’s arguably his first moment of conscience we see from him, as well as a turning point in the film. One of the saddest, most affecting aspects of The Family Man is the fact that it takes Jack longer than anybody else to realize he’s a genuinely good person.

Not to mention the almost zero-sum (“bittersweet” doesn’t quite describe it) note the film ends on. There may be hope for some version of this life together in the future, but this one - the kids, the house, the dog - is gone. (It’s come to my attention recently that many consider the final scene a hopeful one, but I’ve always felt that the conversation shared between the two leads is to be their last.) We’re left wondering whether everything we’ve just seen was a dream, parallel reality, or induced hallucination. Did the people who populated it have thoughts and dreams of their own? If they exist at all, it’s only as part of someone else’s dream—a strange fate.

More Favorites: Transformations

-

Altered States

1980 -

Alien: Resurrection

1997 -

In the Mouth of Madness

1994 -

Now, Voyager

1942 -

Honey, I Shrunk the Kids

1989 -

The Toxic Avenger

1984 -

Teen Wolf

1985 -

Teen Wolf Too

1987 -

An American Werewolf in London

1981 -

The Curse of the Cat People

1944 -

Face/Off

1997 -

That Obscure Object of Desire

1977 -

Now, Voyager

1942 -

From Beyond

1986 -

The Beast Within

1982 -

The Family Man

2000 -

Starman

1984

We don’t do comments anymore, but you may contact us here or find us on Twitter or Facebook.