Reviews

Phillipe Mora

USA, 1982

Credits

Review by Jonathan Foltz

Posted on 22 May 2012

Source Netflix VOD

Categories Favorites: Transformations

There is a wonderful moment in Roman Polanski’s The Tenant, when Trelkovsky, reclined on the bed of a young woman, wonders, “At what precise moment does an individual stop being who he thinks he is?” If he loses a limb? Or two? Vital organs? Only when he removes his head, Tralkovsky reasons, in this oddly morbid snippet of pillow talk, does an individual lose their identity. Still, he protests: “What right has my head to call itself me?” As taken as I am with The Tenant, and Trelkosvky’s obsession with existential disintegration, this is a question much more fully addressed in the gory terrain of horror film than in Polanski’s signature brand of psychological thriller. Horror’s enduring spectacles of monstrosity and bodily harm, with its images of ripped tissue and the bright effluvia of blood and puss, play out Trelkovsky’s anxiety on a sublimely visceral level. Film, of course, is a medium with a special tie to physical reality, which means, too, that it is drawn to the deformed tactility of special effects and the power they have to monumentalize physical mutation. The changed, violated bodies of horror films are also something else: a fantasy that death is as unreal as the actor’s make-up, and a reminder our bodies are not really our own. Our bodies stretch, sweat and flake off, peel, pulse and grow feeble, all without our permission. Nails, skin, ligature and hair: the body is continually at work in a grossly material tectonics that is one of the chief signs of our contingency, our vulnerability, and our animal abjection.

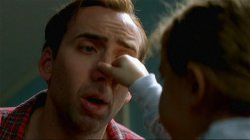

Few films capture the sheer nonsense pleasure of the distended body on film as powerfully as Phillipe Mora’s 1982 puzzler, The Beast Within. Part of the strength of this film is the centrality it gives to its display of special effects, orchestrated here by Thomas R. Burman, the make-up guru who had worked on Planet of the Apes, Paul Schrader’s Cat People and who would go on to do Teen Wolf and Teen Wolf Too. But unlike these slicker productions, in which the scenes of physical transformation are neatly tucked into narrative arcs, in The Beast Within it is as though the visual spectacle of transformation is itself the film’s climax, and that its convoluted story was devised retrospectively in order to make sense of the indeterminate creature that its main character turns into. This is not true, of course - the film was based on a novel - but The Beast Within is so short on explanations for what is happening, and why, that when we finally encounter Michael, pulling off his restraints in a hospital bed, his entire head bulging and peeling, and a troubling slit opening on his shoulder blades where a new mountain of cartilage presses out from the broken skin, we don’t wonder why everyone else in the room just stands there watching it happen. No one, either in the film or in the audience, seems to have any idea what he is turning into (more on this later). The complicated, viscous body that Michael assumes commands such attention that we might forgive ourselves for ceasing to care about any kind of psychological interpretation. Conventional wisdom would suggest that “the beast within” is a thin metaphor for a Freudian well-spring of sexual desire and violent aggression which the mild-mannered Michael keeps locked inside his wavy hair and letterman jacket. Though this remains true at a certain level, what is interesting about the film is how inconsequential this pop-psychological reading actually proves to be. The Beast Within is ultimately not about characters, but about the allure and the irrationality of bodies.

The film follows the beleaguered MacCleary family and their tragic misadventures in the forgotten town of Nioba, Mississippi. In the opening scene, Eli and Caroline MacCleary take a wrong turn on their way to Jackson, and when their tires get stuck in the mud (that old cinematic hand of fate) the husband leaves his wife in the car to go get help. The situation gets worse when Mrs. MacCleary’s spooked dog bolts into the woods and she decides to go after it. When Mr. MacCleary finally returns with help, the dog has been eviscerated and his wife assaulted and raped by a mysterious beast. Skipping seventeen years into the future, we discover that the child born of this violent union - the unassuming Michael - has been suffering from an unknown illness: a “chemical imbalance, an occult malignancy in his system,” says the stilted, uninformative doctor, “a pituitary gland that has gone crazy, out of control!” (This is a diagnosis that understandably prompts Eli to ask in disbelief “What kind of medicine are you practicing here, doctor?”) But Michael is not just crippled by illness; he is also visited by recurring dreams about an empty, decrepit house where a threatening presence menaces him from a locked cellar, asking to be released. But this is not a symbolic cellar - the icon of repression - it is a memory, but not his, of a house in back in Nioba. And Michael doesn’t just dream of going there, he actually escapes from his doctor’s care and, as if possessed, drives up to Nioba, where (coincidentally) Eli and Caroline have also gone to investigate into the identity of Michael’s father in the hopes that something in his genetic make-up will help cure Michael’s illness. But while his parents begin to uncover the criminal secrets of this small town, Michael begins to commit a series of murders that are connected to the crimes and cover-ups that his parents are investigating. In fact, the more we understand about Michael’s murderous urges (“You’re the hungriest, droolingest somebody I ever did see!” remarks one of his folksier victims), the more we understand that he is no longer himself but the reincarnation of Billy Connors, man who raped his mother, who has come back to Nioba in order to take revenge on his tormentors, the Curwin family.

As you might be able to ascertain from this small, and mercifully incomplete, synopsis, The Beast Within has a plot so convoluted that if graphed it would look like a somersaulting Southern Gothic double helix. We eventually find out that Billy Connors, whose consciousness has infected Michael’s, fell in love with Lionel Curwin’s wife, and that when the affair was discovered Curwin killed his wife and locked Billy Connors in the cellar for so long that he turned into… a murderous insect-like beast, which like a cicada, is capable of emerging from his husk every seventeen years. It doesn’t make more sense from the mouth of Judge Curwin in the film’s penultimate scene:

He killed her alright. Yeah. But that wasn’t good enough, ah no. He had to take Billy, lock him up in that cellar. And he kept him there, and he kept him there, and he kept him there! Till Billy couldn’t take it no more, till he was starvin’! And then Lionel, he opened up that cellar door. And he says, Billy… Billy… You still want her, well now you can have her! And he throws her body down. After that it was easy: Lionel, the town undertaker robbing his own coffins to feed Billy his flesh, the human flesh that he needed to live. It was easy!

That anyone would want to keep his dead wife’s lover locked in a cellar, and that he would keep him alive by feeding him human flesh, makes about as much sense as the notion that feeding on human flesh will turn you into an insect-monster (last time I checked, cicadas don’t eat human flesh!). The Beast Within tries to outrun its irrational plot by dolling out information as indirectly as possible. It is common wisdom that cinematic creatures remain frightening so long as they are not shown too directly—The Beast Within takes the same approach to narrative explication. This may explain why Billy Connors is also said to have had “cicada-like” attributes even in his youth, long before his diet of flesh is supposed to have spurred his mutation. The town doctor remembers Billy a “a strange boy—beautiful to look at, though. Tall, silent when he moved. Loved the woods and everything in ‘em. He could talk to the animals, it was said that even the bugs would answer him.” And Billy’s old friend Tom, who recognizes Billy’s voice through Michael’s appearance, muses:

I remember Billy and me listenin’ to my daddy. Used to play a game. ‘Hey Billy, can you do the magic like the locusts and the cicadas? Can you get through anything, by becoming somethin’, somethin’ else? Changing, reborn?’ You believe that shit? Hah hah hah hah!

This “injun palaver” and “local Nioba nonsense,” as the Doctor calls it, is the purest expression of the film’s plot, which clutches so tightly to the cicada metaphors that it is possible to lose sight of the fact that when Michael descends into a murderous rage, he is really taking Billy’s revenge and not acting out a primal, animal instinct. When the young Amanda, Michael’s erstwhile love interest, pricks her finger, Michael smells the blood and the rattle of insect wings rises on the soundtrack. “The cicadas…,” he murmurs as sweat gathers on his forehead and his breathing increases, “they’re in the trees now… in the branches… soon they’ll be shedding their skins… !” Somehow, the overly trusting Amanda - who is a Curwin herself - doesn’t sense that something is wrong, even when Michael rips the handle off her bedroom door and bursts into the room when she’s changing.

The Beast Within is awash with incongruities, but capitalizes on its narrative confusion in the climactic scene in which Michael finally transforms into Billy Connors, or rather, into the cicada-like beast that Billy also transformed into. With his parents, the doctor, and the sheriff all crowded around him, Michael thrashes his face in the throes of his development. But his creaturely transformation seems to have little resemblance to the beast he later becomes. The boils that throb hideously on his face later disappear; the growth sprouting out of from the back of his neck would seem to be wings—but we never see them. At one moment, Michael looks completely inhuman, more like a mole or a rodent than an insect—two seconds later he looks like a standard humanoid monster. It is a testament to the power of Burman’s wizardry that we are less interested to see what Michael becomes, than to bear witness to the sheer eruption of flesh, the sublime inconsistency of Michael’s changing body. Standard werewolf logic would suggest that this transformation is only another way of thinking about the development of the body in adolescence. But in the contorted logic of The Beast Within, we are seeing Michael give birth to the vengeful insect that his father had become. We are of course also watching the film cannibalize its own mixed metaphors, before leaving them all behind, like the husk of Michael’s body which is later discovered in the woods. But rarely has the self-destruction of narrative logic made for such engrossing spectacle!

More Favorites: Transformations

-

Altered States

1980 -

Alien: Resurrection

1997 -

In the Mouth of Madness

1994 -

Now, Voyager

1942 -

Honey, I Shrunk the Kids

1989 -

The Toxic Avenger

1984 -

Teen Wolf

1985 -

Teen Wolf Too

1987 -

An American Werewolf in London

1981 -

The Curse of the Cat People

1944 -

Face/Off

1997 -

That Obscure Object of Desire

1977 -

Now, Voyager

1942 -

From Beyond

1986 -

The Beast Within

1982 -

The Family Man

2000 -

Starman

1984

We don’t do comments anymore, but you may contact us here or find us on Twitter or Facebook.