Reviews

Mad Max 2: The Road Warrior

George Miller

Australia, 1981

Credits

Review by David Carter

Posted on 12 August 2013

Source Warner Brothers DVD

Categories Favorites: The Apocalypse

The Road Warrior enjoys the rare honor of being equally esteemed by viewers, critics, and filmmakers alike. The former two groups paid their respects punctually at the film’s release: it became one of the highest-grossing Australian films of all-time, and Roger Ebert, Vincent Canby, and others praised the film as well as Mel Gibson’s performance and George Miller’s direction. As for those filmmakers, The Road Warrior’s success was less immediately evident, but has with time grown affectionately. Miller’s vision of the post-apocalyptic world (as seen in this film and to a lesser extent in its predecessor, Mad Max) has come to define the very concept of the post-apocalypse for many, as evidenced by the innumerable direct references to The Road Warrior in other films. Its success spawned a deluge of copy-cats in American and Italian cinema, and the influence of its iconic characters can be seen across a variety of film genres, television shows, and other avenues of pop culture. So pervasive was its influence that The Road Warrior’s post-apocalyptic wasteland became the accepted version of the future in the minds of many, defining the parameters of post-apocalyptic cinema in the popular consciousness for the next decade.

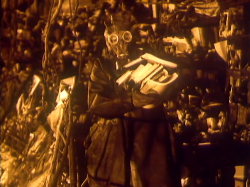

A voice-over provides the back story, spoken over a sepia-toned montage from Mad Max: the “two great tribes” — the US and the USSR — went to war, and the resulting scarcity of resources led to the breakdown of society worldwide. Gas, the most precious of these quantities, is the source of persistent skirmishes in the barren wastelands of the Australian outback, and the film proper opens with Max getting the upper hand in such a fight and subsequently scrambling to capture the leaking fuel from his opponent’s vehicle. Max continues his wandering until he happens upon a makeshift gyro-copter and the strange man who built it. The gyro-pilot tells Max of a “ka-chunk, ka-chunk” — a working oil refinery — a short distance away, and offers to take him there in exchange for his life.

Max and the pilot survey the refinery from atop a rocky bluff. The pilot’s ravings were true. It is a limitless supply of gasoline, and Max begins formulating a plan to obtain it. He’s not alone in in this resolve, however. The forces of the desert bandit “The Humungous” have surrounded the compound, terrorizing and threatening the well-defended village therein. After Max rescues a villager who has been set upon by Humungous’ sadistic assistant, Wez, he uses the dying man to gain entry into the compound, hoping to exchange a life for a tank full of gas. Pappagallo, the group’s leader, has a different idea. If Max will assist them in escaping the desert for the coast, he will be allowed to live with them. Max agrees only to assist them in finding a rig large enough to haul the fuel tanker, but changes his mind about helping them after Wez destroys his vehicle. Max must fend off Humungous’ forces and drive a heavily-armored tanker out of the desert in an effort to save the villagers and perhaps restore his lost humanity.

As influential as The Road Warrior is, it is also a film which readily displays its own influences. The resonances with western and samurai cinema are numerous. Max is a version of the ronin, a masterless samurai, an honorable man that has fallen between the cracks of society. Max’s outsider status is reinforced by the fact that both the innocent villagers and the bandits live in improvised societies, and he refuses to be a part of either. The narrative of the film shares much in common with The Seven Samurai/The Magnificent Seven, with Max filling the role of all seven hired fighters. Stylistically, The Road Warrior echoes many themes from Eastwood’s High Plains Drifter, particularly through Max’s ambiguous morality and the paranoia of the villagers.

It can be argued that the point of The Road Warrior is that Max isn’t a hero by any definition and, that in the context of a post-apocalypse, the concept of “hero” has become irrelevant. Miller’s film rejects most notions of action cinema characterization, such as heroism and villainy, and instead presents a world where survival has replaced any sort of moral code. This is in opposition to the world of Mad Max, where there is still a rudimentary societal code. The Road Warrior, by way of contrast, highlights the fact that there is little difference between Max, Humungous, and Pappagallo. Each is willing to kill the other to get what he wants, or to keep what he has. This can be seen as a critique of pre-apocalyptic society because these attitudes already existed in the men; their current situation has only brought them to the forefront. The underlying message is that war and greed will only beget more of the same, and only selfless acts — such as Max’s piloting of the tanker — can break the cycle.

Above all, The Road Warrior rejects the sentimentality typically associated with action cinema. Death is shown as sudden, pervasive, and meaningless. No one gets a hero’s death in The Road Warrior, and anyone can die at anytime. The film subverts the audiences’ desire to connect with the characters by refusing to give many of them proper names, reinforcing the film’s concept of societal breakdown. Furthermore, the film doesn’t allow the characters to connect with one another either. The only true relationships Max has in the film are with his dog and a feral child from the village, and in these relationships Miller subtly hides another critique of pre-apocalyptic culture. It is implied that since both the dog and the child are “feral,” they lack the selfishness ingrained by society. Therefore they can act in symbiosis with Max for their mutual survivals selflessly. Indeed, Max, the dog, and the child are the only characters in the film which ever make a sacrifice for one another, highlighting that act, rather than violence, as Miller’s concept of true heroism.

The Road Warrior’s ambiguous finale reinforces the idea that it is society itself that is the villain, as it is willing to sacrifice the individual to prolong its own existence. Having realized this, Max refuses the final invitation to become part of the village and join them in their alleged paradise. The Road Warrior’s final scenes invert the endings seen in the westerns from which it has drawn its influence. The villagers, revealed as duplicitous, opportunistic, and — metaphorically, at least — cannibalistic, ride off into the sunset for a life of ease. Max, now clearly shown to be the last honorable and wise man alive, fades slowly into darkness, the road stretching out in front of him, rather than behind. It is a haunting note on which to end a film that precludes sentimentality. We pity the hero because, like him, we realize there is no place for Max in the society the villagers are trying to rebuild. Additionally, like the best of post-apocalyptic cinema, it makes the viewer question their own place in the current society and whether they are delaying or hastening any coming apocalypse.

More Favorites: The Apocalypse

-

The War Game

1965 -

On The Beach

1959 -

Where Have All the People Gone

1974 -

A Boy and His Dog

1975 -

Bug

1975 -

La Soufrière

1977 -

Escape from New York

1981 -

The Road Warrior

1981 -

Le Dernier Combat

1983 -

Night of the Comet

1984 -

Threads

1984 -

The Terminator

1984 -

Def-Con 4

1984 -

Letters From a Dead Man

1986 -

Miracle Mile

1988 -

Last Night

1988 -

Last Days

2005 -

The Rapture

1991 -

Southland Tales

2006 -

Idiocracy

2006 -

The Happening

2008 -

The Road

2009 -

Cosmopolis

2012

We don’t do comments anymore, but you may contact us here or find us on Twitter or Facebook.