Credits

Feature by: Adam Balz, David Carter, Leah Chamberlain, Matthew Derby, Veronika Ferdman, Leo Goldsmith, Glenn Heath Jr., Jordan Holtane, Victoria Large, Michael Nordine, Thomas Scalzo, Rob Weychert, and Rumsey Taylor

Posted on: 30 September 2012

It is at this point every year that the change in season is exhibited in everyone and everything around. The temperature begins to drop and people bundle up a little more as if bracing themselves for whatever discomforts the Fall will conjure. And the Sun, the sole celestial provider of warmth, sets earlier, hastening the dark and cold of the night.

This transition has also a cerebral symptom, one to which we have administered in the celebration of the horror genre. It is a practice that has become our custom, one decidedly in respect to the holiday that sees this season’s climax thirty-one days hence.

2012 marks the ninth consecutive installment of our perennial 31 Days of Horror. Its characteristics should be familiar: for the entirety of October, we will publish a review of a horror film each day. Some of these will not be mainstays of the horror genre, although they possess aspects of the genre’s more salacious or famous entries to which they will be associated. These will span the body of cinema, with particular focus on low-budget scares from the 1970s and 1980s, as well as resurged horror efforts from the ensuing decades. In addition, this year’s installment will see three sidebars that isolate the following sub-genres and filmmakers:

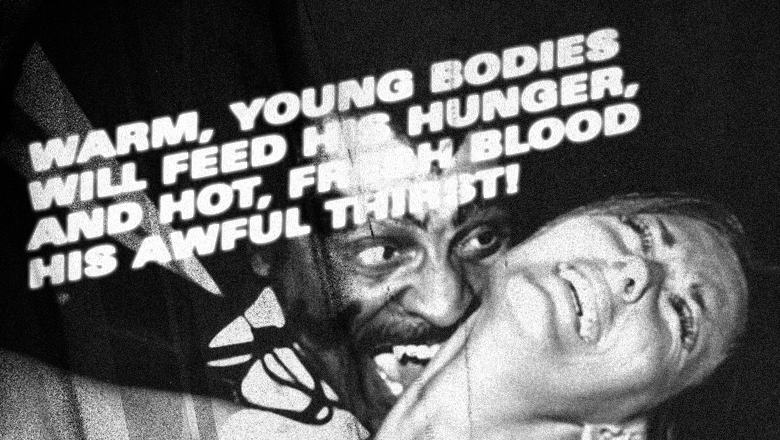

Black Vampires

When Bram Stoker’s Dracula was published in 1897 it introduced the world to what would become one of literature’s – and cinema’s – most iconic monsters. The monster drew immediate comparisons to historical figures like Elizabeth Bathory and Vlad the Impaler, but Stoker’s inspirations for the archetypical vampire seem to have been more contemporaneous: immigrants from continental Europe and epidemics that followed in their wake.

Stoker, however insensitively, was adapting social conditions in turn-of-the-century Britain for use in his novel, investing in his many characters, especially Dracula himself, a complex and touchy metaphorical utility. This utility, over the last few decades, has made its way into Dracula’s cinematic depictions, used extensively by writers and directors of all creeds and colors, including – to much variety and entertainment – African-Americans. On Thursdays throughout the month, we will examine the role of vampires as metaphors, as well as how those metaphors have shifted and changed according to evolving American social mores.

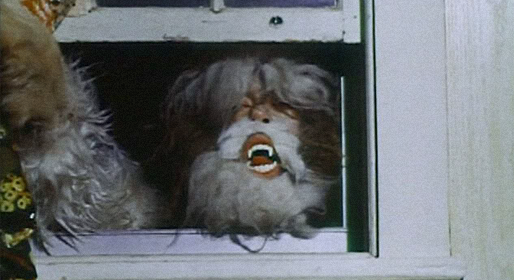

Sasquatch Cinema

When the first European settlers arrived in North America they brought a rich tradition of folklore. The import of such mythology meant that vampires and werewolves would have a place in the fears of the new world. Unbeknownst to these settlers, however, was the knowledge of a hirsute and evasive creature lurking in the wilds of what would become the United States and Canada: the Sasquatch. Known under a variety of regional names but commonly called “Bigfoot,” the creature, according to native North Americans, was either a ferocious predator or a gentle nature spirit, but all concurred on the beast’s inherent elusiveness. Sightings of the creature date into the 1800s, but a debate persists as to what Bigfoot actually is: the fabled “missing link,” an undiscovered species of ape, or simply an endless stream of misidentifications and hoaxes. What is certain is that as one of the only monsters indigenous to North America, the Bigfoot has been woefully underrepresented in American horror cinema. On Fridays throughout the coming month we’ll be taking a look at some of the high and low lights of Sasquatch cinema.

Bill Rebane

Bill Rebane: if you know him, you know The Giant Spider Invasion. And if you know The Giant Spider Invasion, you most likely know the Mystery Science Theatre 3000 version, with its running commentary of good-natured mocking. While it’s certainly true that Rebane’s work, Spider Invasion in particular, is a treasure trove of ridicule-friendly horror, the man should not be dismissed as a mindless moviemaking hack. He may have routinely lacked for funds, but a thorough examination of his output shows a man with an obvious fascination with fantastic tales, and a fierce determination to bring those tales to life. Whether that determination led to relying on hokey special effects or dialogue heavy screenplays, Rebane found a way, time and again, to tell his stories. And that’s what makes Rebane’s films resonate, despite their obvious shortcomings: they are his films. They are labors of love, filled with a charming purity that can only be achieved by an independent artist following his vision. On Sundays this month we’ll take a look at four features from this low-budget auteur from Wisconsin.

By Adam Balz, David Carter, Leah Chamberlain, Matthew Derby, Veronika Ferdman, Leo Goldsmith, Glenn Heath Jr., Jordan Holtane, Victoria Large, Michael Nordine, Thomas Scalzo, Rob Weychert, and Rumsey Taylor ©2012 NotComing.com

Reviews

-

The Addiction

1995 -

Psycho III

1986 -

Wake in Fright

1971 -

Blacula

1972 -

Big Foot

1970 -

Trollhunter

2010 -

Invasion from Inner Earth

1974 -

In the Company of Men

1997 -

Happy Birthday to Me

1981 -

I Drink Your Blood

1970 -

The Legend of Boggy Creek

1972 -

Maximum Overdrive

1986 -

The Giant Spider Invasion

1975 -

Ganja & Hess

1973 -

Not of This Earth

1957 -

Let’s Scare Jessica to Death

1971 -

Next of Kin

1982 -

Def by Temptation

1990 -

Shriek of the Mutilated

1974 -

The Manster

1959 -

The Alpha Incident

1978 -

The Bride

1985 -

Planet of the Vampires

1965 -

The Hole

2009 -

Vampire in Brooklyn

1995 -

Sasquatch: the Legend of Bigfoot

1977 -

Mad Love

1935 -

The Demons of Ludlow

1983 -

Habit

1997 -

Elephant

1989 -

The Blair Witch Project

1999

We don’t do comments anymore, but you may contact us here or find us on Twitter or Facebook.