Reviews

Michael Anderson

USA, 1975

Credits

Review by David Carter

Posted on 04 June 2013

Source Warner Archives DVD

Categories Failed Franchises

Superheroes are identified as the modern Western equivalent of cultural myths. Comic books tell of the exploits of gods, goddesses, heroes, and heroines in much the same manner as The Iliad, the tale of Gilgamesh, or The Mahabharata. In the case of these examples and, indeed, all of classical mythology, the version which has endured into the present day is likely an adaptation of some work that came before it, now long since lost to antiquity.

But the source text for most superheroes is not lost, but is in fact quite well known: Lester Dent’s Doc Savage. Conceived originally to capitalize on the success of The Shadow, Doc Savage was a wholly benevolent version of Street & Smith’s violent and deceptive vigilante. Doc Savage is the American ideal - physically perfect, highly intelligent, incredibly wealthy, and morally pure - traits that would go on to form the basis of the superhero archetype.

Doc Savage waited some forty years to make his big-screen debut, decades after descendants such as Superman and Batman had been adapted into serials, and James Bond, which owes a considerable debt to Doc as well, had become a cinematic franchise. Doc Savage: The Man of Bronze was released in 1975 and was clearly intended to be the start of a Doc Savage filmic franchise: the film even boldly announces its sequel, Doc Savage: The Archenemy of Evil, at the film’s close. However, poor reviews and worse box office receipts quickly scuttled those plans. Man of Bronze had a number of setbacks, primarily a lack of studio support, but matters were not helped by the fact that it debuted in many markets at the same time as Spielberg’s Jaws. While its status as a commercial flop cannot be argued, Doc Savage: the Man of Bronze is much more a victim of circumstances beyond its control than it is a cinematic failure.

We first meet Clark “Doc” Savage, Jr., as he enters his “Fortress of Solitude,” a hideaway in the frozen wastelands of the Arctic Circle. Raised by a team of scientists to reach the limits of human potential, Doc Savage retreats to the Arctic to further his knowledge in various disciplines and to work on inventions to benefit the human race. Savage returns to his New York penthouse for a meeting with the “Fabulous Five” - his multi-talented team of assistants - and learns of the death of his father in the Central American republic of Hidalgo. Savage receives a package from his father mailed shortly before his death, but an assassination attempt prevents him from learning what his father’s final message was. Doc Savage and the Fabulous Five resolve to leave for Hidalgo in the morning to investigate the truth behind the elder Savage’s death.

The arrival of the famous Doc Savage to the small nation draws the attention of adventurer Captain Seas, who invites the Savage crew to dinner on his massive yacht. After bristling when Savage refuses to indulge in alcohol, tobacco, or women, Seas reveals that his invitation was a ruse to assassinate the bronze-skinned hero. The villain’s plan fails, but it strengthens Savage’s resolve to discover what happened to his father, and he leads the Five into the mythical “Valley of the Vanished,” where his father was reportedly living with the lost tribe of Quetzamal. Once there, the team is confronted by Captain Seas again, who has enslaved the Quetzamal to access their endless pool of molten gold. The Fabulous Five are captured and subjected to the “Green Death,” forcing Savage to single-handedly take on Seas’ men and rescue his friends.

Doc Savage: The Man of Bronze is a perfectly serviceable adventure film, neither better nor worse than was typical for the time period. It takes on the format of the standard comic book “origin story” yet the narrative is atypical for the genre. Doc Savage is already at the pinnacle of human achievement - his “superpowers” for lack of a better term - when we are first introduced to him, the particulars of how he became that way are only referenced in a bit of throwaway dialogue. Furthermore, it is implied that heroism is nothing new for Savage and the Fabulous Five, and that the adventure shown in Man of Bronze is merely another chapter in their already storied careers. As a narrative technique, beginning in media res works well for the film, allowing even unfamiliar viewers to accept the more outlandish aspects of the plot, such as Doc’s seemingly bulletproof skin and incredible strength. Doc Savage unfortunately skews towards unsuccessful high camp too often, giving the (incorrect) impression that the film is aimed toward children. This, which includes the Fabulous Five’s groan-worthy attempts at comic relief, emerges as the only major flaw in the film.

But most of the reasons for Doc Savage’s failure are external to the film itself, and chief among these is its timing. Man of Bronze was technically the first non-serialized American superhero film since 1951’s Superman and the Mole Men. Unlike Superman, who has never waned in popularity since his introduction, the original run of Doc Savage pulps ended thirty-six years prior to Man of Bronze’s release, and the character had only appeared in brief comic book runs in the ensuing years. Though reprints of the pulps continued to sell well until the late sixties, Doc Savage was an unknown commodity to most people, not nearly well-known enough to draw theatergoers on name-recognition alone. The filmic Doc Savage’s closest peer, ABC Television’s Batman, had ended its run nearly a decade prior, meaning that the film was poorly conceived in both subject and format.

The cultural climate of America in 1975 was also particularly ill-suited for a patriotic do-gooder described by his creator as manifesting “Christliness.” Doc Savage was released into a post-Vietnam, post-Watergate America, one with little interest in a period-piece starring a hero from the early 1930s. The country was a vastly different place in 1975, and Savage’s unparalleled goodness would have seemed more naïve than admirable. Public faith in American institutions was at an all-time low, and this was particularly of law enforcement: 1975’s Church Committee hearings revealed those who we entrusted to uphold the law were regularly breaking it with impunity. Audiences were looking for films that mirrored their own cynicism (One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, Dog Day Afternoon) or offered them an escape from it (1975’s Jaws, 1977’s Star Wars). In this milieu, Doc Savage would have been interpreted as a painful and unwanted reminder of an innocence lost.

One could say that Man of Bronze was an ill-timed film, but a less-cynical way of phrasing it would be to call it “ahead of its time.” Doc Savage: the Man of Bronze predates Richard Donner’s Superman by three years and the current spate of box office dominating superhero films by decades. The argument could be made that the filmic Doc Savage has proven as influential as his pulp counterpart, albeit more as an example of what not to do.

More Failed Franchises

-

Captain Kronos - Vampire Hunter

1974 -

Doc Savage: Man of Bronze

1975 -

Zorro

1975 -

Flash Gordon

1980 -

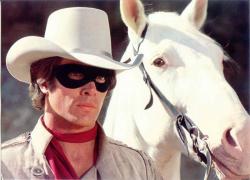

The Legend of the Lone Ranger

1981 -

The Adventures of Buckaroo Banzai Across the 8th Dimension!

1984 -

Supergirl

1984 -

Dune

1984 -

Masters of the Universe

1987 -

Howard the Duck

1986 -

Willow

1988 -

Dick Tracy

1990 -

The Rocketeer

1991 -

V.I. Warshawski

1991 -

The Shadow

1994 -

Godzilla

1998 -

The Zero Effect

1998 -

The Mod Squad

1999 -

Hulk

2003 -

Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World

2003 -

John Carter

2012

We don’t do comments anymore, but you may contact us here or find us on Twitter or Facebook.