Reviews

Russell Mulcahy

USA, 1994

Credits

Review by Victoria Large

Posted on 21 June 2013

Source Universal Studios DVD

Categories Failed Franchises

Sometimes when there isn’t a notable sports game on, restaurants equipped with televisions will tune in to a movie that’s playing on TV. The movie is usually on mute, but patrons who idly glance up can often get the gist of what’s on screen: a Good Guy, a Bad Guy, a Love Interest, a Fight Scene, a Love Scene. I’ve always found this experience kind of comforting; the familiar story plays on, oblivious to an audience that’s either not looking or not fully comprehending. For reasons I’ll get to, I was reminded of that situation a lot while revisiting 1994’s attempted-blockbuster The Shadow.

The pedigree for The Shadow perhaps helps to partially explain the film’s struggle to find an audience. Its titular character was popularized in pulp novels of the Thirties and Forties, as well as a long-running radio series that initially starred a young Orson Welles. But aside from some relatively obscure movies and serials, The Shadow hadn’t proliferated onscreen in the way that heroes like Batman and Superman had. So while The Shadow still lingered in the minds of older audience members in 1994, and the radio show’s catch phrase, “The Shadow knows!” was still part of the popular consciousness, the film and its marketers had the task of introducing the character to a lot of people who knew next to nothing about him.

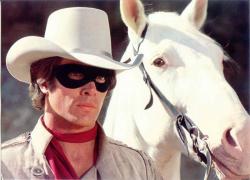

They got some things right. Alec Baldwin, with his rich, distinctive voice and icy eyes, feels like just the right casting choice for a man who is an otherworldly vigilante by night and a handsome playboy, Lamont Cranston, by day. The sumptuous retro production design is also seductive, and I was surprised at how well some of the visual effects hold up, including a flying dagger with a gilded handle that bites. The trouble comes with the storytelling. David Koepp’s script is messy, with an inconsistent tone and action that too frequently feels disjointed. One can watch it - as I did, with notebook in hand - paying close attention, and still end up feeling like someone who has only just looked up from a their salad to see a half-understood scene on TV.

The Shadow is actually an early iteration of what we now call a superhero, predating Batman and Superman, and he has the power to “cloud men’s minds,” which means that he can disguise his identity or even appear invisible (except for his shadow) when fighting crime. He can also pull Jedi-like mind tricks on people as a means of protecting his identity. Koepp gives the character some extra backstory for the film, introducing him as a murderous American opium lord in Tibet (complete with scraggly hair, talon-like fingernails, and an elaborate robe, all of which look kind of comical on Baldwin) who is kidnapped by a mysterious holy man and forcibly convinced to atone for his sins. It’s tough to carp about the fact that the film skips over most of Cranston’s rehabilitation—a lengthy training sequence could have been a really tedious and cliché-ridden addition — but by giving The Shadow such a bloody past, Koepp makes it harder for us to embrace the character, particularly since he isn’t willing to go beyond a few superficial references the evil that lurks in the heart of our protagonist. (Maybe he was saving the heftier character development for the sequel.)

For his part, erstwhile Highlander director Russell Mulcahy seems much more interested in the film’s luxe reimagining of 1930s New York than The Shadow’s vague Eastern origins, reveling in the film’s artificial-but-immersive backlot streets and matte painting skyline. (As others have noted, there are touches of Tim Burton’s Gotham City here.) There’s some great gee-whiz set design, especially where our hero’s hidden lair is concerned. The Shadow is very much an exercise in style, and its pleasures have more to do with how well Baldwin wears a tux, or how perfect his co-star Penelope Ann Miller’s lipstick is, than anything to do with their characters or chemistry.

There’s promise in the film’s premise, and in the ideas behind its individual set pieces, but it too often squanders its own potential. For instance, a scene where Cranston gets trapped in a water tank may sound cool on paper, but onscreen it feels flat and unnecessary, and the Lady from Shanghai-inspired climax was left truncated and confusing due to issues with schedule and budget. Many of the peripheral characters also feel superfluous, including Ian McKellen going mostly to waste as a daffy scientist, and the usually wonderful Tim Curry doing his best with scant screentime as a broadly written secondary villain.

One of the film’s brightest spots is Hong Kong-born actor John Lone, who plays the film’s Big Bad Shiwan Kahn, a descendant of Genghis Kahn who possesses the same powers as The Shadow and is (of course) bent on world domination. Shiwan Kahn could easily be nothing more than a depressing Yellow Peril stereotype, but Lone makes the absolute most of the role, bringing wry humor and considerable charm to what could have been a thankless part. Knowing that he played the vastly different role of Song Liling in David Cronenberg’s adaptation of M. Butterfly in 1993 only makes me appreciate his work here more.

Lone and Baldwin prove best at tapping in to the film’s sly comedy, including a cheeky product-placement parody where the two discuss Cranston’s Brooks Brothers tie. Deadpan comic touches like Kahn hiding, E.T.-style, among some suits of armor, or Cranston ruining a romantic moment by confessing that he dreams about tearing his own face off, ease the frustrations of the muddled story, though the film’s corniest bits are played too straight to really be funny, but too cartoony to be taken to heart.

It’s been reported that, years prior to Mulcahy’s take on The Shadow, Sam Raimi had hoped to make a film based on the character (with Bruce Campbell as the rumored lead!). Failing to secure the rights, Raimi reimagined The Shadow as Darkman, a film that now ironically enjoys a better reputation than its big budget doppelganger. One can’t help but wonder what a big budget Shadow with a young Raimi at the helm would have been like, if he could have maintained a more consistent tone, fusing the film’s inherent gloominess (the hero invades people’s thoughts, and can drive them to madness or self-harm, after all) with the surprising humor that marks his best work.

According to Box Office Mojo, The Shadow, which didn’t make the kind of money that justifies a sequel, was far out-grossed in ‘94 by The Mask, a similarly retro-flavored and special effects-laden fantasy that pursued a more fully comedic style, as well as The Crow, which offered a tortured pulp antihero more in-tune with the pop culture zeitgeist of the time. Today, The Shadow really does feel orphaned, perhaps because its failed plans for world domination are so baldly apparent. It’s clearly meant to be the first of many adventures, as well as a launching pad for action figures, trading cards, and merchandizing of all kinds. The end title music, a song called “Original Sin” belted out by singer Taylor Dayne, is an obvious bid for cross-platform promotion, a preexisting power ballad that was rewritten to include extra lyrics obliquely referencing The Shadow’s plot. Indeed, it feels like more attention was given to selling the film than securing a script worth the big budget gamble, which is actually too bad. The Shadow is a tough film to wholly dislike, even if it does too often seem at a loss about what to do with its own lavish resources. Its familiar trappings give it a comfort food appeal, but there just isn’t enough happening beneath its flashy surface.

More Failed Franchises

-

Captain Kronos - Vampire Hunter

1974 -

Doc Savage: Man of Bronze

1975 -

Zorro

1975 -

Flash Gordon

1980 -

The Legend of the Lone Ranger

1981 -

The Adventures of Buckaroo Banzai Across the 8th Dimension!

1984 -

Supergirl

1984 -

Dune

1984 -

Masters of the Universe

1987 -

Howard the Duck

1986 -

Willow

1988 -

Dick Tracy

1990 -

The Rocketeer

1991 -

V.I. Warshawski

1991 -

The Shadow

1994 -

Godzilla

1998 -

The Zero Effect

1998 -

The Mod Squad

1999 -

Hulk

2003 -

Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World

2003 -

John Carter

2012

We don’t do comments anymore, but you may contact us here or find us on Twitter or Facebook.