Reviews

Joe Johnston

USA, 1991

Credits

Review by Briallen Hopper

Posted on 20 June 2013

Source Walt Disney Home Video DVD

Categories Failed Franchises

I was a bit of a late-bloomer, sheltered and bookish. My hippie parents had raised me in a TV-and-movie-free bubble, and cinema was something we never talked about. Occasionally when I was babysitting at a house with TV I would glimpse a bit of the Friday night movie on PBS - The Last Time I Saw Paris, A Summer Place - and I knew I wanted more, but I had no idea how and when it would ever happen. Then the summer I was thirteen I visited a friend who had permissive parents, and they drove us to the theater, and I finally had my first real big-screen live-action cinematic experience. I lost it at The Rocketeer.

I still remember the thrill of going to the movies for the first time: the plunge into mid-afternoon matinee darkness, the surround sound, the condensation on my paper cup of Coke. But after 22 years all I could remember about the movie itself was that the Rocketeer was handsome and wore a brown leather jacket, Jennifer Connelly’s character was beautiful and wore a white satin dress, and I had a very good time. Even after seeing the movie again, that is still about all I can remember, though luckily I have notes, and there is now an Internet.

The Rocketeer, it seems, is a Disney movie starring Billy Campbell as Cliff Secord, a barnstorming pilot in Depression-era California who discovers an abandoned futuristic jetpack and proceeds to fly around and save the world. Jennifer Connelly is his aspiring starlet girlfriend Jenny, and if they have any chemistry - I couldn’t tell - it might be because Campbell and Connelly also dated for five years in real life. Alan Arkin is Cliff’s trusty mechanic who knows how to patch an injured jetpack with spit, chewing gum, and American ingenuity. The bad guys are Paul Sorvino, a patriotic mobster, and Timothy Dalton, an unlikely Nazi who swashbuckles on filmsets as a day job. The cast was directed by Joe Johnston.

Cliff was based on a retro character created by 1980s artist Dave Stevens, who is said to have brought a dark pulp and bondage sensibility to his independently-published cult comics; he based Cliff’s girlfriend on bondage queen Bettie Page. This edgy sensibility did not translate onto the big screen. In the movie, Jenny is sweet and straitlaced and sans bangs. And unlike all the classic superheroes who have two personalities, Cliff has one to none. In or out of the jet-pack, he is basically a nice guy who likes to fly.

The conventional wisdom on The Rocketeer is that it’s so OK it’s bad. As Owen Gleiberman wrote in his insightful review in Entertainment Weekly:

In Star Wars and Raiders of the Lost Ark, George Lucas and Steven Spielberg took the blandly enthusiastic, B-movie pulp of their youth - everything from Flash Gordon to the old cliff-hanger serials - and gave it a new, hip spin. They seemed to be winking at their material (even as they played it straight). In The Rocketeer, the folks over at Disney do just the opposite: They remove the spin—and what’s left is a piece of blandly enthusiastic, B-movie pulp.

This take is completely true as far as it goes. But the unconventional wisdom on The Rocketeer, or at least my own dissenting opinion a couple decades later, is that there is actually something to be said for cinema without spin—for a take on the pop-culture past that is almost unfiltered, without any of the irony or obsession of Stephen Spielberg or Woody Allen or Todd Haynes or Matthew Weiner or all our other nostalgia artists. In other words, when you take out the wink and the reverence, something is indeed lost, but something is also gained.

The Rocketeer invites a kind of viewing that is utterly un-distanced, with no invitations or indeed opportunities to reflect. It is well-made enough to keep you watching without ever wincing or fuming or wondering why. The cast is high-quality, but the casting is completely generic, with no interesting friction between actors and their roles. The movie’s many verbal and visual references (to Errol Flynn, Hollywoodland, Howard Hughes, the Hindenberg) are instantly gratifying but do not lead anywhere. Like a good first boyfriend, the movie wants to give you a pleasant time for a couple hours and then leave you more or less how it found you. Like a box of Crackerjacks, it has a small, simple, dependable charm.

This slight success is the cause of the film’s failure as a franchise. In the end there is really nowhere for the story to go: the Rocketeer has no villains left to vanquish, no split personality to struggle with or secrets to keep. There is no momentous mythology or backstory to explore—no Kryptonite or spider bites. There is no enduring geography like Gotham City, no social allegory as in the X-Men. There is only a pocket rocket and a happily-ever-after kiss.

Still, for me, The Rocketeer was a pretty perfect first movie. It served as a crash course in the types, plots, and settings of the Golden Age of Hollywood, carelessly blending together the 30s, 40s, and 50s: Depression-era hard times and escapist stunts, mobsters with hearts of gold, villains with an English accent, villains with a German accent, diners, dames, airplanes, inventors, movies about movie-making, and women torn between love and career; everything I would need to know in order to begin plowing through the VHS section of the public library in earnest. And it initiated me into a kind of movie-watching that I practiced for the next decade and still sometimes miss: unblinking, unwinking, too close for camp; the straight-up consumption of old pop culture in a world without Stanley Cavell. As the Rocketeer says about jet-pack flying, “It’s the closest I’ll ever get to heaven.”

More Failed Franchises

-

Captain Kronos - Vampire Hunter

1974 -

Doc Savage: Man of Bronze

1975 -

Zorro

1975 -

Flash Gordon

1980 -

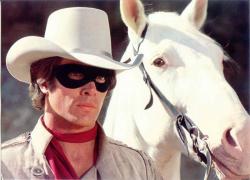

The Legend of the Lone Ranger

1981 -

The Adventures of Buckaroo Banzai Across the 8th Dimension!

1984 -

Supergirl

1984 -

Dune

1984 -

Masters of the Universe

1987 -

Howard the Duck

1986 -

Willow

1988 -

Dick Tracy

1990 -

The Rocketeer

1991 -

V.I. Warshawski

1991 -

The Shadow

1994 -

Godzilla

1998 -

The Zero Effect

1998 -

The Mod Squad

1999 -

Hulk

2003 -

Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World

2003 -

John Carter

2012

We don’t do comments anymore, but you may contact us here or find us on Twitter or Facebook.