Reviews

Peter Weir

USA / Australia / UK, 2003

Credits

Review by Daniel Schwartz

Posted on 01 July 2013

Source 20th Century Fox DVD

Related articles

2000—2009: The Decade in Review The Best Movie of the Decade that You Probably Didn’t See

Categories Failed Franchises

Director Peter Weir has admitted that, although it performed “well… ish at the box office,” Master and Commander: The Far Side of the Word “didn’t generate that kind of monstrous, rapid income that provokes a sequel.”1 The film derives from Patrick O’Brian’s Aubrey-Maturin series of novels, which follows Captain Jack Aubrey and his surgeon sidekick Dr. Stephen Maturin during the Napoleonic Wars. O’Brian’s series has, to date, spanned twenty books and sold well over two million copies, calling into question the failure of Weir’s film to capitalize on the popularity of O’Brian’s franchise.

Unlike numerous other big-budget failed franchises, Master and Commander was not unprofitable. The film brought in $212 million on a budget of $150. Furthermore, the film was nominated for ten Academy Awards and won two. On the other hand, the movie exceeded its initial budget, made only $93 million domestically, and reaped the majority of its profits overseas. This may explain why Crowe’s Twitter campaign for a sequel fell on deaf ears in 2010. As far as the studio was concerned, Weir had it right: the “monstrous, rapid income” just wasn’t there, and as to why this was the case is a matter of speculation. But since the books were so popular it’s worth examining what may have been lost in Master and Commander’s transition from page to screen. Simply put, the film failed to retain many of the qualities that made O’Brian’s series a success.

I should acknowledge that I am in no way an O’Brian fanatic, and my familiarity with his work is limited to the Aubrey-Maturin series. I have, however, seen enough of the series to make some judgment. (The writing doesn’t appear to change much from book to book or, for that matter, improve any.) I am continually baffled by the list of literary greats to whom O’Brian is so often compared. Gary Krist put it best in his review, “Bad Art, Good Entertainment,” when he wrote, “the Aubrey/Maturin books… are potboilers, plain and simple.”2 Weir’s film didn’t mar a classic series so much as it failed to capitalize on the inherent commercial aspect of what was at its base popular entertainment.

Perhaps nowhere was this clearer than in the film’s characterization. Jack Aubrey, as depicted in O’Brian’s prose, possesses a vigorous lust for life that rubs off on comrades and readers alike. In the first of the books Jack tests the cannons of his new ship, not only to see if they work, but to admire their “lovely smell.” His love of seamanship is evident throughout, as is his love of people. Jack is very concerned with the happiness and harmony of his crew, for, as he is wont to remind readers, “there is nothing pleasanter than good shipmates.” Ultimately we sympathize with Jack because he is warm and passionate—the heart of the series.

Russell Crowe’s conception of Jack Aubrey, on the other hand, is stoic. Much of this may be due to Crowe’s effort to emphasize Jack’s authoritarian aspects. But this is by and large the only side of Jack that we ever see in the film. Apart from a few drunken cracks, Crowe spends the film looking either sullen or grave. And with the main character remaining so aloof, the audience is accorded little entrance into the film.

The improbable friendship that develops between Aubrey and Maturin constitutes a major part of the books’ appeal. Aubrey is a strapping, lusty sea captain, while Maturin is a poetic, highly cerebral physician. Together, the two rebound off one another to charming and often comic effect. Not so in the film, in which there is little chemistry between the two. And what chemistry there is is expended on tired ideological quarreling. In the film, Jack and Stephen’s biggest scene together involves an argument over whether to stop off at the Galapagos or continue after a French frigate. Stephen is all for the Galapagos; Jack is all for the frigate. The discussion soon devolves into abstractions: Science vs. Mission, Humanism vs. Patriotism, and other such platitudes. In the end it’s hard to see how these two are even friends, let alone lifelong comrades.

O’Brian’s crackling dialogue is also missing. In the novels Maturin could be counted on for a witticism on occasion, as when, in the first book, he explains his disaffection with nationalism:

[Y]ou know as well as I, patriotism is a word; and one that generally comes to mean either my country, right or wrong, which is infamous, or my country is always right, which is imbecile.

In the film we must content ourselves with bad puns. Aubrey, after Maturin has selected the larger of two insects, quips: “Don’t you know that in the Navy you must always choose the lesser of two weevils?” The same line appears in O’Brian’s sixth book, The Fortune of War. But there the joke is self-conscious. In the book, we are encouraged to laugh at Aubrey as well as with him, for having attempted to pass off a lousy pun as a comic triumph.

Master and Commander is often compared to the first Pirates of the Caribbean movie, and Pirates is said to have lacked the former’s gritty realism, moral seriousness, and taut performances. Indeed, but the film was fun to watch. Sitting through battle scenes featuring the sluggish, grimacing Jack Aubrey, I found myself longing for the kinetics of Jack Sparrow, his high-flying acrobatics and marvelous derring-do. What Sparrow lacked in believability he more than made up for in style.

I am well aware that I’m squarely in the minority with regard to the film’s critical consensus. As the critics have rightly noted, the movie wasn’t totally brainless, and it wasn’t just a cash-in on a built-in audience, even if it was based on a best-selling series. Weir and Crowe were serious about producing something of artistic value; they were trying. Looking back, however, I’m glad things ended where they did.

- “What hath Peter Weir wrought?” The Seattle Times, August 10th, 2005 ↩

- “Bad Art, Good Entertainment”, Gary Krist, published in The Hudson Review, Vol. 47, No. 2 (Summer 1994), pp. 299—306 ↩

More Failed Franchises

-

Captain Kronos - Vampire Hunter

1974 -

Doc Savage: Man of Bronze

1975 -

Zorro

1975 -

Flash Gordon

1980 -

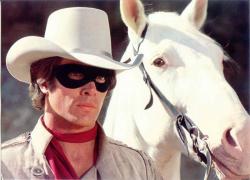

The Legend of the Lone Ranger

1981 -

The Adventures of Buckaroo Banzai Across the 8th Dimension!

1984 -

Supergirl

1984 -

Dune

1984 -

Masters of the Universe

1987 -

Howard the Duck

1986 -

Willow

1988 -

Dick Tracy

1990 -

The Rocketeer

1991 -

V.I. Warshawski

1991 -

The Shadow

1994 -

Godzilla

1998 -

The Zero Effect

1998 -

The Mod Squad

1999 -

Hulk

2003 -

Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World

2003 -

John Carter

2012

We don’t do comments anymore, but you may contact us here or find us on Twitter or Facebook.