Reviews

Ang Lee

USA, 2003

Credits

Review by Rod Bastanmehr

Posted on 27 June 2013

Source Universal Studios DVD

Categories Failed Franchises

First and foremost, it is questionable as to whether Hulk, Ang Lee’s reasonably well-received 2003 superhero film, should be considered a failed franchise. It was followed by another Hulk film five years later in an effort to reboot the material into another origin film. Soon after, the character was merged into The Avengers in 2012, which - as a part of the Marvel Comics Cinematic Universe - constitutes one of the most popular movie franchises in Hollywood history. The Hulk, it seems in retrospect, is inadequate when posited as the sole superhero in a movie (the 2008 film has also yet to spawn a sequel).

Hulk is something of an admirable mess, and it should be considered within its context: the summer after Spider-Man reignited the escapist superhero wave, and two years before Batman Begins would christen the grittier adaptations most commonly associated with the most recent wave of comic book cinema. Hulk’s cast and crew - including Jennifer Connelly, who had just won an Academy Award, and Ang Lee, himself a four-time nominee - grant the film a certain credibility, but the largest problem isn’t that it’s an overly serious film, but rather that it never takes itself lightly. Whereas Spider-Man is both focused and subversive, Hulk is tonally muddled. It counters a vibrant pop art aesthetic (akin to that of Scott Pilgrim vs. the World) with pathos, and narratively it becomes less comprehensible as it goes on.

What makes the Hulk such an interesting character within the pantheon of comic book heroes is that he has always been one of the few whose power is presented as an ostracizing curse. Lee, who has repeatedly considered the ramifications of familial conflict, would find weight in the traditional superhero subtext of loss as an emotional catalyst. In keeping with this approach, the screenplay takes liberties with the Hulk’s origin, by catalyzing his transformation in both the repression of childhood trauma and gamma radiation. (It’s also revealed that Bruce Banner’s father used himself as a test subject for an unsanctioned mutant DNA stream, and that his augmented genes has been passed down to his son.) The psychological elements of the character’s power are questioned: if a man is able to turn into a beast with a single flicker of rage, what does that say of the man as opposed to the beast?

For a film so devoted to presenting a medley of complex human relationships and emotions, Hulk remains opaque in its intentions, and one’s investment in the material is hindered in comparison to more generic and accessible superhero movies. The narrative is emotionally convoluted: flashbacks are layered within flashbacks, and by the time the film ends, its primary conflict is too visually abstract to fully comprehend. There is no traditional villain bent on world domination, no threat on a grand scale. Everything is smaller in presentation but larger in an emotional or theoretical realm. When Bruce’s father returns, he adopts a genetic mutation that gives him the ability to absorb the elements and energy of everything he touches, yet by the film’s climax, the character has receded to an ethereal presence rather than a visceral one, and Banner’s final showdown with him is more intellectually jarring than it is bombastic.

It wouldn’t be until the midpoint of the new millennium that superhero films would become more grounded in pathos, with a propensity to render feeling as well as spectacle. For some, it would be by making us sympathize with both the hero and his human alter ego (Robert Downey Jr. in Iron Man); for others, it would be by depicting post-9/11 cultural anxieties through the framework of fantasy (the Dark Knight trilogy). Hulk predates these examples, and in this respect warrants acknowledgement for its humanistic characterization of a supernatural hero.

But despite its narrative complications and difficulty in centralizing the inner conflict of its characters, Hulk is nevertheless a unique visual feast, sublime in its conception of a computer-generated character. When the army is firing at Hulk, which constitutes much of the film’s third act, the bullets bounce off his skin with such smoothness that his form is realistically defined. When landing on lush sand dunes - the expansive burnt orange terrain of a Nevada desert behind him - the Hulk inhabits the physical space with an apparent gravity. And in the finale, there is something nearly profound about the effect Hulk’s presence has on the viewer, watching his green body and purple shorts against the blue sky and bright orange clay of the southwestern desert. For a film that attempts to cut to the core of being human, it’s still the spectacle that manages to get at something more.

More Failed Franchises

-

Captain Kronos - Vampire Hunter

1974 -

Doc Savage: Man of Bronze

1975 -

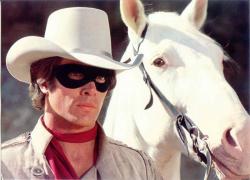

Zorro

1975 -

Flash Gordon

1980 -

The Legend of the Lone Ranger

1981 -

The Adventures of Buckaroo Banzai Across the 8th Dimension!

1984 -

Supergirl

1984 -

Dune

1984 -

Masters of the Universe

1987 -

Howard the Duck

1986 -

Willow

1988 -

Dick Tracy

1990 -

The Rocketeer

1991 -

V.I. Warshawski

1991 -

The Shadow

1994 -

Godzilla

1998 -

The Zero Effect

1998 -

The Mod Squad

1999 -

Hulk

2003 -

Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World

2003 -

John Carter

2012

We don’t do comments anymore, but you may contact us here or find us on Twitter or Facebook.